《Imaginary Games》书摘:什么是游戏?

作者:Chris Bateman

什么是游戏?

2010年4月,著名影评人Roger Ebert遭到口诛笔伐,他在自己的博客中写道电子游戏不仅不算艺术,而且永远也无法成为艺术。由于网络上充斥着大量誓死捍卫游戏这种娱乐形式的粉丝,因而这类言论不可避免地遭致许多人的口诛笔伐。

从各个方面上来说,Ebert愿意涉足这个话题是游戏行业之幸,因为各种媒体对这个行业的评论很少,甚至对其抱有蔑视态度,因而数字游戏媒介确实需要严肃地考虑这个话题。

何谓艺术?何谓游戏?我们很容易产生这只是个语义学问题,不值得进行探讨的想法。

他在博文中引用了希腊哲学家的说法,表示艺术“可以通过所谓的艺术家灵魂或愿景来提升或改变人类的本性”。辩论正是基于这个前提而产生的,游戏作为以目标为导向的行为,不能被视为艺术,或者换个说法,游戏中追求胜利的因素就是对艺术性的亵渎。

但是,并非所有我们称之为“游戏”的东西都包含胜利的观念。儿童的模仿游戏不需要胜利观念,多数的桌面角色扮演游戏也不需要,从本质上来说,后者是儿童模仿游戏的更高级形式。

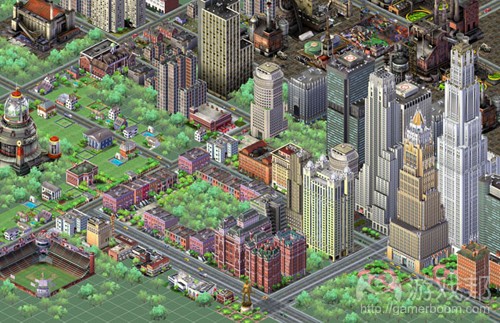

诸如《ring a ring a roses》之类的韵律游戏没有胜利的概念,某些电脑游戏也摒弃了追求某个目标的理念,Will Wright将自己的游戏《模拟城市》称为“软件玩具”。还有许多其他的游戏在这点上则显得模棱两可,比如经典的8位游戏《Deus Ex Machina》。

Ian Bogost在2009年数字游戏研究协会(游戏邦注:即DiGRA)的主题演讲中承认,游戏研究中的多数讨论正受限于这个问题。“什么是游戏?”Bogost回顾这个关键问题的研究历史,深刻地总结了该讨论所取得的“进展”。

首先,游戏学和叙述学间的争论,焦点是要将游戏视为规则系统还是虚构事物。但是Bogost指出,这是种错误的对分方式。所提出的问题类似于“游戏是否是个规则组成的系统,就像故事是叙述组成的系统一样?”如果这样阐述问题的话,两者间的分离就不存在了,答案也是显而易见的。

Jesper Juul在名作《Half-Real》中阐述了这场争论的下个重大进展:

电子游戏同时兼有两个不同的层面:电子游戏是真实的,因为它们是由玩家可以互动的真实规则构成;在游戏中胜利或失败都是件真实的事情。但是,当游戏胜利是杀死一条龙时,龙并非真实的,而是游戏虚构的。因而,玩电子游戏就是在与真实的规则互动,同时想象出虚拟世界背景。电子游戏既是真实规则,也是虚拟世界。

如此看来,游戏被视为兼具规则系统和虚构事物两个层面。Bogost批判的不是这种说法,而是其潜在的臆断。即便事实就是如此,规则也占据着首要的地位,因为游戏中有些部分(游戏邦注:通常是规则)比其他部分更具真实性。于是,我们进入了实体论的哲学领域,讨论的是存在和真实的问题。如果有人提出某物是真实的言论,他们提出的就是有关实体论的问题。在不久后的辩论中,这点变得很重要。

Juul提出了第三次辩论,什么才是适合游戏研究的领域:是游戏本身还是玩家?

这使得行业产生了一种想法,游戏只有在玩家占有它们时才“存在”。Bogost将此比作Kant的突破认知,人类只能通过思维和知觉来接触所有存在的东西。如果我们用这种方式来看待问题,那么我们处理的就不再是“什么是游戏?”这个问题,探究的是游戏的实体论含义。

Bogost在介绍自己的实体论研究时提到了自己的观点,这个观点是基于他同Nick Montfort合作开展平台研究得出的。他系统化地揭露数字游戏的许多不同成分,将游戏视为缺失其他关键层面的规则。

在《Racing the Beam》中提到的Montfort和Bogost研究Atari VCS的案例中,硬件和软件局限性会对游戏会产生不同的影响。他们公开了许多数字游戏本质中的潜藏要素。

根据Levi Bryant和Graham Harman的实体论相关著作,尤其是“水平实体论”的观点,Bogost大胆地建议我们在游戏理解方面放弃纳入等级制度的想法。

他的说法是,从水平实体论(游戏邦注:即所有的实体都处在相同层面上)的角度来理解游戏是较好的选择。Bogost在此基础上进一步深入,建议我们跃过实体论元素中有关人类的部分,采用更为广阔的视角:

游戏研究不只意味着研究适合玩家的游戏或适合游戏的规则,还包括适合规则的电脑、适合电脑的操作逻辑、适合指导的注册方式和适合电子枪的无线电频率。游戏并不只与人类有关,它还涉及处理器、塑料弹壳、消费者等内容。

尽管他使用了Harman和Bryant的面向对象实体论揭露出某些有趣的问题,但好像还是没有回答我们需要探索的问题。事实上,我们对此问题也并没有一致的答案。

游戏和娱乐

Midgley于1974年发表哲学著作《The Game Game》,成为第二名探究“什么是游戏?”的哲学家。不幸的是,这篇文章几乎不为哲学和游戏研究两个领域所知晓,虽然文章内容与随后的探索领域的基础问题间存在关联。

Bernard Suits是首个探索这个领域的哲学家,最早在1967年通过题为“什么是游戏?”的文章触及这个话题,但其观点同样不为人知。

这是件很不幸的事情,因为Midgley和Suits所著内容对游戏概念的解读很有作用。有趣的是,这二人的方法都对某个更为著名的哲学家嗤之以鼻,那就是奥地利哲学家Ludwig Wittgenstein。

深入探究Wittgenstein巨作《Philosophical Investigations》之后,我们可以发现他将游戏视为所谓“家族相似性”的例子。他调查的结果是,各种类型的游戏(游戏邦注:包括桌游、卡片游戏和球类游戏等)之间并没有具体的相似之处,但是却被一系列共性和关系连接在一起。

他将此比作家庭成员呈现出的共同特征,比如相似的鼻子、身材和发色等。Midgley和Suits批判的正是Wittgenstein这种“你无法找到所有游戏的共同点”的看法。

在《The Game Game》中,Midgley根据Julius Kovesi的作品得出自己的观点。Kovesi的作品中有着同样质疑Wittgenstein的“家庭相似性”概念的内容,他还以家具为例来阐述需求和概念间的关系,表示正是因为你理解了椅子所承载的需求(游戏邦注:即椅子可供人坐),你才能明白椅子与其他家具特征不同的原因。这个例子也可以运用于其他问题。正如Midgley指出的那样:

通常来说,只有你理解了需求,才能够明白要去寻找何种特征。要了解椅子的特征,就只需要理解需求就可以了。

因而,尽管人们在游戏相关细节的意见上存在分歧,但是我们都能够准确地运用游戏概念,因为它背后存在一个实体支撑物。因为游戏满足人类的需求,因为人类本性有着自己的结构,所以我们知晓游戏的构建成分。要理解“游戏”概念的含义,就需要去了解游戏满足何种需求。

刷任务

探索我们玩游戏需求的方法之一是深层次地挖掘游戏体验生物学。这其中涉及到多种关键化学成分,比如让人类产生兴奋感的肾上腺素,兴奋是人类玩游戏的最首要的情感。

带有机会和竞争的游戏给这种天然的兴奋感加上某种能够产生欣喜感的胜利状态,促发胜利者举起手臂的正是这种胜利感,Suits将此描述为“只有最高程度的成功才能够产生的真正愉快心情”。这种情感无法用单个英文词来表达,但是研究人员Paul Ekman指出意大利语词汇“fiero”可以表达这种情感,也就是人们度过逆境的胜利感。为便于理解,在下文中我将用“胜利感”来表达这种情感。

胜利感体验与某些最为流行的娱乐形式之间存在密切联系,其弱化版本“满足感”则与神经传递素多巴胺有所联系。这种奖励性的化学物质主要由大脑边缘系的奖励中枢释放,产生满足和生理的情感体验。

这种神经结构对行为的形成至关重要,也能够通过像B.F. Skinner和Charles Ferster所描述的那种奖励程序(游戏邦注:也称为强化程序)产生强制性。

John Hopson等人表示,基于这些系统的游戏机制是数字游戏所特有的,尤其是电脑角色扮演游戏和MMO。在玩家保持对游戏任务的兴趣的同时,他们会很高兴去挑战游戏所指派的任务,只要这些任务能够提供奖励。

但是,当他们开始失去兴趣时,他们就会逐渐意识到自己只是在做一系列高度重复性的任务以推动游戏进程。玩家们将这种行为称为刷任务。

当玩家在刷任务时,他们希望能够不断积累游戏内的资源(游戏邦注:通常是金钱或经验值)以实现更高的目标,每个目标都会给玩家提供某种奖励,比如力量或技能等级提升。经济学家Edward Castronova将这个过程比作科林斯王的神话,这个希腊神话中的君王不断将巨石推向山顶,但是石头最终还是会滚下来。

不过Castronova也指出,游戏中的刷任务机制并非毫无用处:当玩家到达山顶时,石头从山顶滚到下个山谷中,而当科林斯王将石头滚上下个山顶时,他发现自己变得更加强大了。如此反复,科林斯王征服了一座又一座的山峰,但是在这个过程中,他不断获得力量。

刷任务经常受到批判,原因在于玩家注意到自己在做的就是重复劳作,他们已经对这种事情失去了兴趣。从现实情况看,那些依靠奖励程序来构建玩法的游戏比不采用这种方法的游戏更容易维持玩家兴趣。假如游戏所要求任务仍能引起玩家的兴趣,那么这显然就是刷任务机制在发挥作用。虽然有些游戏设计师尝试开发不使用这种刷任务机制的游戏,但是采用该机制的游戏在数字游戏领域却极有市场。

某些玩家偏爱包含刷任务机制的游戏有一定的原因,因为刷任务机制通常能够阶段性地鼓励玩家继续玩下去,这意味着在某些领域缺乏技能的玩家可以简单地通过刷任务来增加力量(游戏邦注:也就是“升级”),由此来得到补偿。

游戏的胜利感可能会因这种难度自我调节元素而受到影响,但这种机制却可以为技能并不高超的玩家创造获胜的公平机会,他们仍然可以通过收集或完成游戏中的相关目标获胜。

刷任务是某些数字游戏,也就是那些使用奖励程序来构建玩法的游戏吸引玩家的重要环节。虽然这些机制刚开始只用于幻想类角色扮演游戏中,但是现在许多其他游戏也使用了这种方法。汽车模拟系列游戏《玛莎拉蒂》的吸引力部分来源于可以通过不断重复比赛来赚取金钱,从而购买更好的车辆。

《现代战争》是将奖励程序运用到第一人称射击题材数字游戏的成功实例,为游戏市场的销售量奠定了新基准,这款游戏在市场中的销售量达到2000万份。现在许多游戏通过奖励结构和刷任务直接以玩家大脑中的奖励中心为驱动目标。

边缘系统的奖励中心和大脑中的另一个结构有紧密联系,那就是大脑中的眼窝前额皮质。

从本质上说,这是大脑中的理性决定中心,它是我们的神经系统中与伏隔核关系最密切的部分,而多数多巴胺由伏隔核产生。做出明智的决定让人感到喜悦,这也就解释了为何我们会认为解决谜题很令人快乐的原因。当我们找到解决方案时,大脑就释放出了多巴胺。

很多游戏基于此神经生物学机制创造乐趣,包括国际象棋和西洋跳棋,其中直接竞争会进一步强化做出优秀决策的乐趣。国际象棋的趣味不仅在于赢得游戏,还体现在如何在当前棋盘状态下打败其他玩家,这就是为什么报纸上的国际象棋谜题颇受用户青睐:若你对这类谜题很感兴趣,那么解决谜题本身就是个愉快的过程。

国际象棋其实就是生成有待解决谜题的游戏,很多业余爱好游戏及拥有各种忠实粉丝的决策型复杂棋盘游戏亦是如此,虽然这类游戏还有其他吸引之处。

但这更多涉及决策中心和奖励中心的联系,而非解决谜题。剑桥大学研究人员表示,即便我们在某操作中失败,决策中心也会释放多巴胺(在我们几乎将要获胜的情况下)。

换而言之,当我们即将接近胜利时,边缘系统就会促使我们进行下个尝试。我把此机制称作“坚持不懈”(grip),它可以说明为何赌场及某些数字游戏即便缺乏奖励依然能够富有沉浸性。

游戏将玩家带入“再试一次”状态主要依靠坚持不懈机制:玩家觉得自己会在下次尝试中获胜因而滋生继续下去的欲望。老虎机也是靠此机制吸引玩家。

虽然这涉及运用神经生物学机制,但坚持不懈机制有自己的鲜明特点。记住刷任务的玩家进行的不过是重复操作,收集游戏资源。受坚持不懈机制影响的玩家也希望自己未来能够得到奖励,但其成就具有不确定性。

刷任务玩家知道他们最终会收集到足够资源赢得奖励;受坚持不懈机制影响的玩家只相信他们最终会获得胜利(游戏邦注:这就是为什么老虎机能够给赌场创造丰厚收益)。

持续操作有时也能够创造坚持不懈效应。决策中心让玩家确信自己一定能获得奖励,只是时间早晚还不确定。因此,坚持刷任务的玩家通常无法停下来,若他们终于成功促使自己停下脚步也依然无法从游戏中走出,并希望自己能够尽早重返游戏。锁定目标的玩家特别容易陷入坚持不懈和刷任务的循环,因此比瞄准过程的玩家更容易沉迷于游戏中。

我自己更倾向于瞄准目标,我深深着迷于电脑角色扮演游戏。2000年在诺克斯维尔时,我因玩角色扮演游戏《口袋妖怪》(《宠物小精灵》)而患上严重失眠症。

我深受游戏奖励结构控制,从而很长时间内处于坚持不懈状态,总是希望重返游戏,这样我就能够升级我的妙蛙种子或让皮卡丘重回正常状态。那年我在这些游戏中投入好几百个小时,我绝对不是唯一沉浸于《宠物小精灵》虚幻世界的玩家——该游戏的原Game Boy版本当时售出了惊人的4500万份。

在缺乏刷任务元素的情况下,坚持机制就会出现在玩家追求胜利的过程中,配合多巴胺的大量释放:玩家想要获胜,在他们相信自己能够胜出的情况下,坚持不懈机制会促使他们继续体验。但为强化胜利体验,融入种种逆境非常必要。

在博彩游戏中,这可以通过提高赌注实现(游戏邦注:风险越大,回报就越高),但在竞争游戏中这则通过直接冲突体现出来。这会带来沮丧感,主要同神经传递素的去甲肾上腺素有关。

Nicole Lazzaro也发现,富有难度的谜题也能够带来胜利感;这似乎是因为决策和边缘系统的奖励中心存在密切联系(这就如同奖励中心同坚持不懈机制存在的关系)。

值得一提的是睾丸素在维持竞争体验中的作用。自上世纪70年代以来,人们就认为睾丸素同固执和韧性相关,当玩家战胜逆境时,睾丸素就直线飙升。这并不是说高水平睾丸素是产生fiero这种骄傲感的必要条件,而是说是具有高水平雄性激素的族群(男女都一样)更容易在挑战中持之以恒,从而取得胜利。换而言之:具有较多睾丸素的玩家会在未分胜负的挑战中坚持不懈。

记住兴奋感同肾上腺素有关,竞争同去甲肾上腺素有关。这使得这两种基础体验模式同战逃反应相对应,Walter Cannon于1929年首先发现这点。愤怒是战斗欲望的基础,同竞争相对应,而恐惧则是逃跑的主要原因,涉及眩晕和兴奋感觉。

但需注意的是,竞争性游戏无需充满愤怒情绪,令人兴奋的体验无需让人胆战心惊。低程度的沮丧感(愤怒)无法激活求胜玩家的意识,虽然它们的神经化学原理一样,但兴奋和恐惧是截然不同的体验,只有后者与扁桃腺这个大脑的恐惧中心有关。

此外,战逃反应涉及的化学联系与坚持不懈的奖励多巴胺有关系,因为前者的两种化学元素来自后者。其实从寒武纪时期进化来的所有多细胞动物都有运用这三种儿茶酚胺化学元素(游戏邦注:从蚂蚁到斑马)——虽然所涉及的化学反应在特定情况下有所不同。从生物层面支撑游戏体验的化学元素与多数奖励&生存行为机制所涉及的化学元素相同。

不可预见性

人类学家Thomas Malaby对体验和游戏非常感兴趣,而且基于此话题发表众多精彩的论文,着重谈及体验在当代希腊文化中的作用。Malaby关于游戏的一个重要发现是:它们是由人类行为维持的过程。但属于哪种过程?

他发现“游戏从本质看缺乏规律”,偶然性在游戏中扮演重要角色,日常体验的不可预知性抵消游戏和生活存在的普遍隔阂:游戏创造不可预知性,但生活本身就难以预知。游戏非常擅于创造偶然因素,因为能够预测的游戏很快就会变得乏味。

不确定因素虽然重要,但不是全部内容。Malaby发现,游戏的第二重要特性是能够创造意义。许多游戏情境都以无法完全预见的方式进行,“需要以某种方式进行诠释,从而形成某种普遍认可的意义”。

此意义生成机制是游戏体验的重要组成要素,完全呈开放模式。不仅体验方式能够调整,所生成的意义也会发生改变。

游戏内部状态的意义感知是理解多数游戏体验的关键,特别是数字游戏。进行更复杂的游戏并非总是旨在获胜,虽然这构成部分动机。

游戏的回馈因素就是游戏规则带领玩家进入的认知状态。关于这点,没有任何作品的呈现方式比《模拟人生》或我和Gregg Barnett共同设计的《鬼魂大师》更清晰,在两款作品中,多数玩家的乐趣主要与他们谈论在屏幕中乱跑的小角色的故事有关。

在这里故事元素起着举足轻重的作用。故事也是过程,和Malaby的游戏一样,它们的目标也是变得引人注目或富有粘性,能够通过自己的内部状态生成意义。我们倾向这样认为,和游戏不同,故事内容是固定、静止的——但下此结论有些为时过早。

也许故事生成的最重要状态是参与者的情感状态(包括书籍的读者,戏剧的观众),这些确实会发生改变,故事内部状态的意义也会发生改变。

此外,不确定性对故事而言非常重要。人们常说“故事关乎冲突”,但这是种简化说法。的确,冲突是常见故事叙述策略,但很多故事缺乏明确冲突,例如基于误解的爱情故事,运气非凡的白手起家故事,探险故事,这些故事都通过制造悬念维持读者的兴趣。

优秀故事内容的普遍要素是不确定性及玩家获悉下步进展的欲望,冲突只是生成不确定性的众多方式之一。这突出故事和游戏之间的关系,强调体验和艺术的关联性。

Malaby最后将游戏定义成“生成可诠释结果的半有界合法人为偶然性”。这有些拗口,这些词语表明游戏体验发生于特定空间中(游戏邦注:这通常被称作魔法圈)。

这里的关键点是游戏涉及需要诠释的人为偶然性。故事亦是如此。其他本身不具有明确叙述性的艺术形式也同样如此;我不确定如果Jackson Pollock的作品不是供大家随意诠释的人为偶然内容,大家会怎么理解其作品内涵。

Malaby作品呈现的体验视角不同于其他游戏研究观点,因为Malaby并不把玩游戏视为一种状态,而是将其看作态度。他表示,根据William James的说法,“玩游戏是指置身快速变化未知世界能够即时做出反应的态度”。

Malaby因此认为当我们进行体验时(不论是在游戏,还是在现实生活中),我们总是会对活动采取特殊态度,这是种不同于正式社会文化(例如货币制度或官僚主义)的态度(后者总是“旨在产生确定结果”)。

因此在Malaby后,有人将游戏看作以特定方式通过不确定性创造诱人和富有粘性体验的过程,但最好的解释还是愿意面对不确定性时进行即兴发挥。因此玩游戏是我们对待不确定性的态度,

同时也是我们利用此态度设计、模拟或者甚至是制止偶然性,诠释结果的游戏过程。矛盾的是,游戏在此定义下无需具有玩乐精神,尽管游戏概念就是取决于玩乐的含义。

我想要进一步说明的是,这种玩游戏的含义可以扩展至艺术世界——-我们也可能将艺术理解为这种过程:我们用对待不确定性和偶然性的态度创造的诱人和富有粘性的体验,并让我们以富有意义的方式诠释其中状态。

艺术世界通常是严肃性的游戏,是值得尊敬的庄重文化内容。就如M.C. Escher所述:“我的艺术是款游戏,一款非常严肃的游戏。”简而言之,我想说的是称游戏非艺术并不合逻辑,因为从某种角度看,所有艺术都是游戏。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

What Is A Game? An Excerpt From Imaginary Games

Chris Bateman

What is a Game?

In April 2010, esteemed film critic Roger Ebert walked unknowingly into the teeth of a rancorous beast when he posted on his blog that not only were video games not art, they could never be art. Given that the internet is packed to its virtual rafters with belligerent gamers who will argue to the death over the insignificant minutiae of their preferred forms of play, this inevitably unleashed a storm of criticism.

In many respects, it was a boon for the games industry that Ebert had chosen to wade in on this topic, since there were enumerable critics in various media who would simply have treated the entire subject with disdain. Whatever one makes of Ebert’s claims, he at least had the respect for the medium of digital games to consider this topic seriously.

But what is art, and what is a game? There is a temptation, as Ebert observed, to think that this is simply a matter of semantics and thus not a big deal — an attitude embodying a rather wide prejudice against philosophy which Ebert, thankfully, does not share.

He quotes from the Greek philosophers in saying that art “improves or alters nature through a passage through what we might call the artist’s soul, or vision,” and constructs an argument based on the premise that, as goal-oriented activities, games are precluded from being considered art or, to put it another way, the possibility of winning in a game is anathema to artistry.

Yet not all things we call a ‘game’ include the notion of winning. A child’s game of make-believe need not, and neither do most tabletop role-playing games, which are, at heart, a more sophisticated form of exactly the same thing as children’s make-believe.

A rhyming game like ‘ring a ring a roses’ doesn’t involve winning either, and certain computer games are equally divorced from an overarching goal — Will Wright has called his game SimCity (Maxis, 1989) a “software toy”, and there are many other games with ambiguity in this regard, such as the classic 8-bit title Deus Ex Machina (Croucher, 1985).

Before we can do justice to Ebert’s argument, we must first establish with some confidence what we mean by the term ‘game’, and this is no easy matter. In fact, this has been recurring theme in the literature of game studies, which from the outset has involved nearly endless discussions concerning the boundary conditions of games.

For the most part, we are no closer to an answer than we were when we began, but it is interesting to note that a great deal of the debate presumes that there is a definitive answer to be reached. The fact that people seem confident the term can be unraveled gestures at an underlying unity to the concept of a game, and thus suggests that the problem is not wholly insoluble.

In his 2009 keynote for the Digital Games Research Association (DiGRA), Ian Bogost admits that so much of the discussion within game studies has been dominated by this very question, “what is a game?” In an insightful summary of the ‘moves’ offered thus far, Bogost covers the history of this crucial investigation.

First, there was the ludology vs. narratology debate, which hinged upon whether games were best understood as a system of rules, or as fictions. But as Bogost notes, there is a false dichotomy in this approach. The question being asked is akin to “is a game a system of rules, like a story is a system of narration?” — and worded this way, the sense of disjunction is removed and the answer is simply returned in the affirmative.

Jesper Juul provided the next major move in this debate, by suggesting in his seminal book Half-Real (2005) that:

…video games are two rather different things at the same time: video games are real in that they are made of real rules that players actually interact with; that winning or losing a game is a real event. However, when winning a game by slaying a dragon, the dragon is not a real dragon, but a fictional one. To play a video game is therefore to interact with real rules while imagining a fictional world and a video game is a set of rules as well a fictional world.

Games are thus suggested to be both systems of rules and fictions. Bogost criticizes not this claim, but an underlying assumption that even if this is the case, the rules somehow have a kind of precedence — some part of a game is more real than the other part (usually the rules). It is here that we reach the philosophical domain of ontology, where questions of being and reality are discussed. If someone makes a claim concerning what is real, they are asking an ontological question. This point will become important shortly.

Juul once again provides Bogost’s “third move” — the question of what is the appropriate area of study in respect of games: is it the games in themselves, or the players?

It leads to an idea that games ‘exist’ when players occupy them, which Bogost compares to Kant’s breakthrough realization that whatever things may exist, we as humans only have access to them via our thought and senses. Once again, seen in this way we are no longer addressing the question “what is a game?” so much as we are dealing with the ontological implications of games.

Bogost has his sights in this keynote on introducing his own ontological move, based on the platform studies he has conducted with Nick Montfort. Here, a number of different component levels of digital games are systematically uncovered — looking as games as just rules misses out on many key aspects.

In the case of the Atari VCS that Montfort and Bogost study in Racing the Beam (2009), the hardware and software constraints had distinct effects on the games that were (or could be) made. There are hidden elements in the nature of digital games to be teased out.

Drawing on the work of Levi Bryant and Graham Harman in ontology, and in particular the notion of a “flat ontology”, Bogost boldly suggests that we entirely abandon attempts to claim a hierarchy of some kind in understanding games.

A game, he offers, is better understood from the perspective of such a flat ontology, one in which no one kind of entity has precedence over another (as in the case of the rules taking precedence over the fiction in Juul’s half-real paradigm). Bogost goes further, suggesting we can look beyond the ontological elements that involve humans and throw the remit far wider such that:

…game studies means not just studies about games-for-players, or as rules-for-games, but also as computers-for-rules, or as operational logics-for computers, or as silicon wafer-for-cartridge casing, or as register-for-instruction, or as radio frequencies-for-electron gun. And game is game not just for humans but also for processor, for plastic cartridge casing, for cartridge bus, for consumer… and so on.

It’s a fascinating discussion that Bogost develops, one that takes a great deal of contemporary philosophy in its stride, and offers a refreshingly wide stance of its subject matter. But while his application of Harman and Bryant’s object oriented ontology reveals some interesting questions, it’s not clear that it answers the question we set out to explore in this chapter.

The matter at hand, you may recall, is “what is a game?” and it’s far from clear that this is best dealt with as an ontological question. Ontology is principally concerned with what exists, the nature of being, or, in its wider scope, the grouping and relationships between entities. There is an ontological aspect associated with games, as we’ve already seen with Juul’s concept of half-real, but to get to this kind of discussion requires a prior conception of what we mean by “game”.

Bogost could not reach the conclusion that game studies should include such esoteric areas of exploration as the relationship between registers and instructions, or radio frequencies and electron guns, had he not already established that registers, instructions, radio frequencies and electron guns were all involved with games in some way. His conclusion presupposes a certain concept of a game. It is only by deploying this concept (whatever it is) that he is able to recognize the many things involved in digital games.

Treating “what is a game?” as an ontological question will not settle it once and for all, although that is not to say that ontology doesn’t have an important role in a philosophical investigation of games. There are in fact some rather crucial questions in the intersection between games and reality — and particular that nebulous concept “virtual reality” — that warrant addressing.

For the time being, though, we must set this domain of philosophy to one side in order to undertake a philosophical investigation as to what the unifying concept behind “game” might be given that we can so easily and confidently act as if we know what a game is, despite not actually agreeing on any particular answer to the question “what is a game?”

Games and Play

The whole of philosophy can be understood as conceptual investigation — as attempts to explore how the concepts of language (and those behind language) are deployed, as enquiries as to the relationship between our concepts and what we term reality, and as rigorous examination of the consequences that concepts and systems of concepts produce. The British moral philosopher Mary Midgley has suggested that one can appreciate the purpose of philosophy by a comparison with plumbing (2005).

Most of the time, we just accept that our conceptual plumbing is doing its job, but every now and then we detect weird smells from underneath the floor boards and must take them up and examine what’s going on behind the scenes. It is time to take a crowbar to the floor of game studies and find out what lies underneath.

In her 1974 philosophy paper “The Game Game”, Midgley became only the second philosopher to tackle the question of “what is a game?” This paper, I’m sad to report, is largely unknown in both philosophical and game studies circles, despite its relevance to the foundational question in the latter domain’s area of exploration.

The first philosopher to explore this space, Bernard Suits, initially approached the subject in a 1967 paper actually entitled “What is a Game?” which he later revised and expanded into his 1978 book The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia.

Sadly, Sarah Hoffman (2009) has suggested that among the philosophical community Suits’ work remains largely unknown, and Midgley’s paper is similarly quite obscure.

This is unfortunate, since Midgley and Suits between them have much to offer that is useful in decoding the game concept, and interestingly both of their approaches involve something of a swipe at another philosopher who is far more well-known — Ludwig Wittgenstein. Indeed, Thomas Hurka in his 2005 introduction to Suits’ The Grasshopper has suggested that Suit’s book is “a precisely placed boot in Wittgenstein’s balls.”

Working towards a deeper understanding of language in his magnum opus, Philosophical Investigations (1953), Wittgenstein specifically singles out games as an example of what he calls family resemblance. He observes that the vast variety of games — board games, card games, ball games and so forth — have nothing specific common between them, but instead are tied together by a series of commonalities and relationships.

He relates this to the way in which members of a family display common traits — a similar nose, or build, or hair color, for instance. It is precisely Wittgenstein’s claim that “you will not see something that is common to all [games]” that Midgley and Suits take task with.

Suit’s complaint is that Wittgenstein asks us to “look and see” if there is anything common in all things we call games, but then doesn’t do so himself. Suits thus objects that Wittgenstein had “decided beforehand that games are indefinable”, and indeed accuses Wittgenstein of believing in the “futility of attempting to define anything whatever”.

Alas, Suits seems to have thoroughly misunderstood Wittgenstein’s purposes, for despite the explicit reference to games it is a point about language that the Austrian philosopher was trying to make, namely that the way words come to be used does not originate in definitions; definitions are post-hoc justifications for the way words are used, and it is this usage that Wittgenstein insists is the genuine meaning of the word, not any definition we might propose.

Midgley accepts Wittgenstein’s main point, but disagrees with his use of family resemblance to characterize the underlying concept. As she noted to me earlier this year (2010), words such as ‘game’:

…have neither a single, fixed meaning (which was what Wittgenstein pointed out) nor merely a vague string of resembling meanings (as his idea of family resemblance suggested) but a definite shape, an underlying organic unity which is often mysterious but must be present in the background to account for e.g. their being usable as metaphors.

She observes, indeed, that Wittgenstein is quite dependent upon understanding the word “game” in a particularly subtle way, for without this he cannot make use of his idea of a “language game” which is a central concept in his later philosophy. This is only possible because we do have a general grasp of the concept of a “game” and can thus understand appeals to this concept in a wider context, such as in the case of Wittgenstein’s language games.

In “The Game Game”, Midgley (1974) draws from the work of Julius Kovesi to develop her argument. Kovesi had very similar issues with the apparent nebulosity of Wittgenstein’s concept of “family resemblance”, and his argument can be felt resonating in Midgley’s paper. In his book Moral Notions (1967), he had been pursuing a rigorous argument counter to the attacks on moral philosophy by A.J. Ayer and G.E. Moore and others that had attained considerable notoriety in the first half of the twentieth century.

Kovesi demonstrated the relationship between needs and concepts by the example of particular kinds of furniture, claiming that provided you understand the need that (say) a chair embodies (i.e. to support a person while sitting), you know what characteristics are relevant in distinguishing a chair from other kinds of objects. This example generalizes to other cases. As Midgley observes (directly following Kovesi) “in general, provided you understand the need, you know what characteristics to look for. To know what a chair is just is to understand that need.”

Thus — despite disagreements over the details concerning games — we are all perfectly able to deploy the concept of a game precisely because there is an underlying unity to it. It is because games meet human needs (and, for that matter, animal needs), and because human nature has its own structure, that we can identify what constitutes a game. Those needs that a game meets are precisely what is involved in understanding what the concept ‘game’ must mean.

Grip and Grind

One way of exploring our need to play is to dig deep into the biology of the gaming experience. There are a number of key chemicals that can be identified, such as the neurotransmitter epinephrine (or adrenaline), which is the underpinning of excitement — the most primal of the emotions of play.

Games of chance and competition add to this raw excitement a winning state that produces feelings of elation that cause the victor to punch the air or raise their arms, what Suits describes as “the truly magnificent exhilaration that can be produced only by a supreme triumph”. There is no word in English for this emotion, but the researcher Paul Ekman (2003) notes that in Italian it is called fiero, the personal triumph over adversity. Since this word is unfamiliar to most English speakers I will use the term triumph as a synonym.

The experience of triumph is intimately involved with some of the most popular forms of play and this emotion, and its watered-down version satisfaction, can be correlated with the neurotransmitter dopamine. This reward chemical is principally released by the reward center of the brain’s limbic system, the nucleus accumbens, and is involved in emotional experiences of satisfaction and triumph.

This neural apparatus is vital to the formation of behavior, and can also generate compulsion via reward schedules (or schedules of reinforcement) of the kind identified by B.F. Skinner (1938) and Charles Ferster (1957).

Game mechanics based upon these systems are endemic to digital games, as John Hopson (2004) and others have observed, especially in the case of computer role-playing games and MMOs. While the player maintains interest in what the game is asking them to do, they will merrily jump through whatever hoops they are pointed towards, provided there is some reward to be paid out.

However, when they begin to lose interest they will become aware that they are being asked to perform a series of highly repetitive tasks in order to achieve some measure of progress. Players call this the grind and the associated activity grinding, and compare it to a metaphorical treadmill. The comparison is apposite — but it is important to remember that the hamster often enjoys running on their wheel.

When a player is grinding, they are expected to keep accumulating an in-game resource (usually either money or experience points) in order to reach progressively higher targets, each target affording the player a reward in terms of increased power or capability. Economist Edward Castronova has gainfully compared this to Camus’ account of the myth of Sisyphus, the mythological Greek king who was condemned to roll a boulder up a hill repeatedly, only to have it roll back down again.

But Castronova notes that it is not quite this futile in a game with grinding: when the grinding player reaches the top of the mountain, the stone goes over the top and rolls into the next valley, and as Sisyphus goes to roll it up the next mountain he discovers he has become more powerful. Again and again, the grinding Sisyphus conquers one mountain to find another behind it — but all the while, they have the sense of achievement from having gained a little bit of power in the process.

Grind is often singled out for criticism, but this is because when players notice they are grinding, they have already lost interest in the activity they are being asked to perform. Pragmatically, those games which rely on reward schedules to structure their play can maintain interest for radically greater lengths of time than those that do not — and provided what the player is asked to do does retain some interest, the grind is precisely what maintains the player’s interest. While some game designers try to develop mechanics which avoid the grind, games that make use of grinding are becoming increasingly significant in the commercial market for digital games.

There are sound reasons for certain players to prefer games which include grinding, since the mechanics behind grinding usually afford progressive advantages to players for continuing to play, and this means that players with a lack of skill in a particular relevant area can compensate by simply grinding to increase power (“level up”).

The sense of triumph may ultimately be less because of this self-adjusting element of difficulty, but this also means that success is not restricted to the players with the necessary skills (or tenacity) to overcome. Furthermore, players open to grinding can still achieve triumph by aiming for thoroughness — completing collections, for instance, or doing everything possible that the game presents as a goal.

Grinding is an important part of the appeal of certain digital games, namely those which utilize reward schedules to structure the play. Although these mechanics began in fantasy role-playing games, they are now found in a great many other games. The appeal of the car simulator series Gran Turismo (Polyphony Digital, 1997 onwards) lies in part in the capacity to grind races in order to earn money and thus buy bigger cars.

The Modern Warfare franchise (Infinity Ward, 2007 onwards) has applied reward schedules to the already successful first person shooter (FPS) genre of digital games and as a consequence set new benchmarks for sales, selling 20 million units in a market that previously topped out at about 8 million. A great many games now directly target their players’ reward centers via reward structures and grind.

The reward center of the limbic system also has incredibly close structural ties to another part of the brain, the orbito-frontal cortex which lies in the brain at a position just above the eyes.

This is essentially the rational decision center of the brain, and there is no other part of our neural architecture more closely tied to the nucleus accumbens, where most dopamine is produced. Making a good decision is pleasurable, and indeed this explains why solving puzzles is enjoyable: when we find the solution, it triggers a release of dopamine.

There are many games which rely upon this neurobiological mechanism for their enjoyment, including chess, checkers and so forth, where direct competition further enhances the enjoyment of making a good decision. The fun of a game of chess lies not just in winning the game but in solving the challenging problem of how to beat the other player given the current state of the board, which is why chess puzzles in newspapers and the like enjoy an audience: solving puzzles is inherently enjoyable, if you’re sufficiently interested in the kind of puzzle to want to solve it.

Chess is in effect a game which generates puzzles to be solved, and the same is true of a great many hobby games, the relatively complex, decision-focused board games that enjoy a cult following among geeks of all stripes, although these often have other dimensions to their appeal as well.

Game Advertising Online

But there is more to this connection between the decision center and the reward center than solving puzzles. Researchers at Cambridge University (Clark et al, 2009) have shown that even if we fail at an activity, the decision center will release dopamine if it assesses that we nearly won.

In other words, when we come close to triumph, the limbic system spurs us into another attempt. I have called this mechanism grip, and it explains why gambling and certain digital games can be addictive even in the absence of reward schedules.

When a particular game gets the player into a state of wanting “just one more go”, it is because of grip: the feeling that one might succeed (or do better) on another attempt fosters the desire to persevere. Slot machines depend upon this for their appeal (if you didn’t win with that coin, surely you will have a better chance of winning next time!).

Although related to grind at the neurobiological level, grip is quite distinct in character. Recall that a player who is grinding is repeating the same activities, accumulating an in-game resource. A player caught in grip is also pursuing future reward, but its attainment is uncertain.

A grinding player knows they will eventually collect enough of their resource to win their reward; a player experiencing grip only believes they will eventually win — which is partly why slot machines are so effective at making money for casinos.

As it happens, grind also generates grip. The decision center assesses the future reward — and this reward will certainly be achieved, the only uncertainty is when.

As a result, players caught in grinding often have great difficulty stopping, and if they do manage to stop they remain under the game’s spell, and anxiously desire to return to it at the earliest possible moment. Players who tend towards goal-orientation are particularly at risk to both grip and grind, and as a result are more likely to become addicted to a game than a process-oriented player.

I myself tend heavily towards goal-orientation, and as my wife will testify I become terribly addicted to computer role-playing games — to the extent that nowadays I’m not allowed to play them except under special circumstances (such as I am working on the development of one). While living in Knoxville in 2000, I had terrible insomnia because I was playing Pokémon (Game Freak, 1996), a computer role-playing game about training fantasy creatures.

I was so caught up in the grind of the game’s reward structures (i.e. improving the abilities of my pet creatures) that I was in a state of perpetual grip, always wanting to get back so that I could evolve my Bulbasaur or get my Pikachu to just the right state. I spent several hundred hours playing those games that year, and I was by no means the only player to be sucked into the fictional world of Pokémon: the original Game Boy games sold an astonishing 45 million units between them.

In the absence of grind, grip occurs when the player is in pursuit of triumph, which corresponds to a large release of dopamine: the player wants to win, and while they believe they can win, grip will motivate them to continue trying. But in order to produce this potent experience of triumph it is necessary for there to be adversity to overcome.

In games of chance, this can be attained by raising the stakes — the bigger the risk, the greater the reward — but in games of competition this is attained by direct conflict. This brings in frustrations (i.e. anger) which are associated with the neurotransmitter norepinephrine. Nicole Lazzaro (2004) has also correctly recognized that difficult puzzles also produce triumph; this appears to be because of the close link between the decision and reward centers of the limbic system we have already seen in connection with grip.

It is also worth briefly noting the role of testosterone in sustaining competitive play. Since the 1970s, testosterone has been connected with persistence and tenacity, and testosterone levels spike when player’s triumph over adversity. It is not that high testosterone is a requirement to experience Ekman’s fiero, it is that people with high levels of this androgen (male or female — its effect on behavior is not gender-specific) are more likely to persist against a challenge and thus attain victory (Andrews et al, 1972; Oades 1978; Booth et al, 1989; Mazur et al, 1997). To put this another way: players with high testosterone levels are more susceptible to the grip of an undefeated challenge.

Recall that excitement relates to epinephrine, and that competition can be related to norepinephrine. This makes two of the basic patterns of play correspond with the two sides of the fight-or-flight response, first observed by Walter Cannon in 1929. Anger is the underpinning of the desire to fight, and corresponds to competition, while fear lies beneath the urge to flee, and relates to experiences of vertigo and excitement.

It must be noted, however, that a game of competition need not be angry, and an exciting play experience need not be fearful. A low level of frustration (anger) will not even reach the conscious awareness of a competitive player, and although their neurochemistry is identical, excitement and fear are distinct experiences, with only the latter involving the amygdala, the brain’s fear center.

What’s more, there is a connection between the chemical correlates of the fight-or-flight response (epinephrine and norepinephrine) and the reward chemical dopamine involved in grip, grind and triumph, since the former two chemicals are synthesized from the latter. In fact, essentially every multi-cellular animal that has evolved since the Cambrian makes use of these three catecholamine chemicals — from ants to zebras — although the actual chemistry involved is slightly different in certain cases. The chemicals that support play at the biological level are the same as those involved in the most basic behavioral mechanisms of reward and survival.

Interpreting Unpredictability

The anthropologist Thomas Malaby has taken a particular interest in play and games, and has published a number of fascinating papers on the subject (2007, 2009), with particular reference to time he spent studying the role of play in contemporary Greek culture. One of Malaby’s key observations concerning games are that they are processes, sustained by human practice. But what kind of process?

He notes that “Games are, at root, about disorder”, recognizing a central role for contingency in games, and suggesting that the incredible unpredictability of our everyday experience bridges the gap between games and life in general: games contrive unpredictability, but life is by its very nature always already unpredictable.

Contriving contingency is one of the things that games excel at, since games which are readily predictable rapidly become boring.

The element of uncertainty, while crucial, is not the whole of the matter. Malaby (2007) observes that a second crucial aspect of games is their capacity to generate meaning. The many kinds of situation that can occur within a game (including but in no way restricted to the goal states and final outcomes, such as winning) happen in never wholly predictable ways and are “subject to interpretations by which more or less stable culturally shared meanings are generated.”

This generation of meaning is a critical aspect of the game experience, and it is thoroughly open-ended. Not only can the way games are played alter within any particular social group, but the meanings that a game can generate can also change.

This appreciation of the meaning of the internal states of games is crucial to understanding the play of a great many games, and particular of digital games. The more complex games are not always undertaken for the sake of winning, even if this forms part of the framework of motivation.

No, what is rewarding in a game is the interpretability of the states the rules of the game throw into the player’s awareness. Nowhere is this more clear than with a game like The Sims (Maxis, 2000) or the game I designed with Gregg Barnett, Ghost Master (Sick Puppies, 2003), where a great deal of the player’s enjoyment is in the stories they tell about the little people running around on screen.

There is an important connection at this point with stories. Stories too are processes, and like Malaby’s games they aim to be compelling or engaging, and possess a characteristic capacity to generate meaning by their internal states. There is a temptation to say that, unlike games, the content of stories is fixed, static — but this reaction is premature.

Perhaps the most important states generated by a story are the emotional states of the participant –the reader of a book, the viewer of a play — and these do indeed change, and the meaning of the internal states of the story also change (for instance, upon seeing the end of a movie, we may have a different understanding of what happens in the middle).

Furthermore, uncertainty is central to stories. It is oft said that “stories are about conflict”, but this is a gross simplification. True, conflict is a common storytelling device, but there are many stories without express conflicts, such as love stories which rest upon misunderstandings, rags-to-riches tales of outrageous fortune, and adventure stories, all of which sustain the reader’s interest by maintaining curiosity.

What is common to all well-regarded stories is uncertainty, the desire to discover what happens next, and conflict (i.e. competition) is just one of many ways that uncertainty can be generated. All this underlines the affinity between stories and games, and emphasizes the connectivity between play and art.

Malaby ultimately defines a game as “a semibounded and socially legitimate domain of contrived contingency that generates interpretable outcomes.” This is something of a mouthful… Much of the wording goes to acknowledging that there is a special space that play occurs within — what is often termed the magic circle — but that it is porous (“semibounded”).

The key point is that games are about contriving contingency to be interpreted. This is also true of stories. It is equally true of many other forms of art that are not expressly narrative in nature; I am unsure how Jackson Pollock’s work is to be understood if it is not a form of contrived contingency intended to be open to interpretation.

The perspective on play presented in Malaby’s work is refreshingly distinct from the usual tropes in game studies, for Malaby (2009) insists on seeing it not as a state (which would make it just a different aspect of a game) but as a disposition. He asserts, with reference to William James (1961) that “play becomes an attitude characterized by a readiness to improvise in the face of an ever-changing world that admits of no transcendently ordered account.”

Malaby thus recognizes that when we play — in games or in life — we are adopting a particular attitude towards our activity, one that is fundamentally different from the attitude expected in the formal games of culture (such as the institution of money or bureaucracy) which “aim to bring about determinate outcomes”.

Thus, following Malaby, games can be understood as processes that utilize uncertainty in particular ways to create compelling and engaging experiences, while play is best understood as a willingness to improvise in the face of uncertainty. Play is thus an attitude we adopt towards uncertainty, and games processes that may make use of this disposition, contriving, simulating or even suppressing contingency so that we might interpret what results. Paradoxically, games on this reading need not be undertaken in a playful spirit, even though the notion of a game may depend upon an understanding of play.

I want to make the further claim that this understanding of play and games extends to the world of art — that art too can be understood as processes that make use of our attitude towards uncertainty and contingency to create compelling and engaging experiences and that invite us to interpret their states in meaningful ways.

The world of art seems akin to play undertaken in seriousness, play that has acquired a kind of cultural gravitas and esteem. As M.C. Escher put the matter: “My art is a game, a very serious game.” In short, I want to assert that it is incoherent to claim, as Ebert does, that games cannot be art, since seen from the appropriate perspective all art is a game.(source:Gamasutra)

上一篇:分享构建灵活的游戏系统的注意要点

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号