分析主题与机制不协调对游戏造成的影响

作者:Gil

在本系列文章中,我将阐述两个存在关联的问题。

首先,注意主题与机制的交汇点。其次,努力让二者之间不发生冲突。

讨论主题是否比机制更为重要的文章很多,反之亦然。但是,我们这里将探讨的并非这个问题。我将要关注的是主题与机制交汇之处以及它们是否恰当吻合。

我自己设计的游戏《Wag the Wolf》就遇到了这个问题。这款游戏的主题是媒体公司努力向全世界做广告。

这听起来像是个愚蠢和喧闹的主题。这是款有趣的游戏,但是其表现趣味性的方式并非如你所愿。游戏中没有无聊乏味的卡片系统。

因而,我发现新玩家充满热情地坐下来玩这款游戏,随后感到糊涂和困惑,因为他们玩到的游戏并非自己期望中的那样。出现这种认知偏差并非好现象。

从另一个角度来看。如果我告诉你我们即将玩的是款有关股票市场的游戏,你会期望它是款类似象棋或冰山棋之类的二人纯战略信息类游戏吗?

或者说如果我们将要玩的是款忍者用激光攻击海盗的游戏,那么如果你看到游戏中采用的是拍卖和创新性卡片机制,但是你无法通过任何方式来攻击其他玩家,你会有何感想呢?

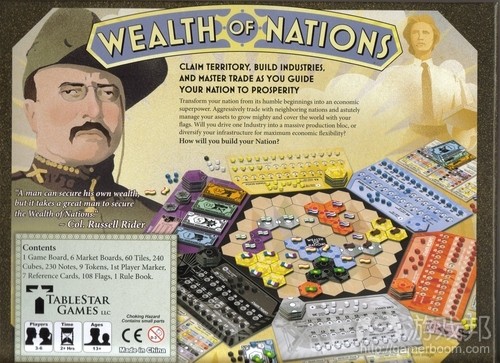

再举个例子。有款很棒的游戏却没有受到认可的游戏是《Wealth of Nations》(国富论)。

看下这款游戏的名称,然后告诉我你认为游戏应该是什么样子的。很显然,游戏看上去同古典经济学家Adam Smith的经济学著作很相像。游戏很可能以殖民主义时期为被背景,主要内容是新兴美洲国家努力与依然强势的大英帝国和欧洲强国对抗,平衡其经济系统。可能会有许多小规则将游戏同这个时期联系起来。

但是事实情况并非如此。《Wealth of Nations》是款相当枯燥的欧洲各国谈判游戏。当然,游戏中也有“国家”,但是它们都是虚构的。

《Wealth of Nations》是款深受经典电脑游戏《M.U.L.E.》影响的桌游,后者取得了令人难以置信的成就。但是前者与18世纪经济并无关联,尽管你可以从游戏中学到重要的供求关系。

这意味着原本应该会想玩这款游戏的欧洲粉丝首先会抵制它,因为他们认为这是款并不会让他们产生兴趣的经济战争游戏。而想要玩这款游戏的战争游戏粉丝会感到失望,因为游戏主题并不具有历史风味。

当然,那些最终坐下来玩《Wealth of Nations》的人得到的是一款有着梦幻般经济系统、内容丰富的游戏。但是游戏需要历经重重艰险才能够为玩家所接受。

那么,这便是以上提到的第一点。玩家会根据你的主题来推断机制。如果玩家发现实际情况与期望存在偏差,他们会感到困惑。而这种困惑正是你需要解决的问题。

但是,这里是否存在可操作的空间?富有天赋的设计师能否将不好的主题转变成吸引人的游戏呢?

Jim Doherty是我最喜欢的设计师之一,他设计过许多有着荒唐主题的游戏。《Monkeys on the Moon》的主题是月球表面的某个猴子种族用火箭将文明程度更高的敌手赶回地球。《The Nacho Incident》的主题是将墨西哥黑市中的食品走私到加拿大。

我很希望能够告诉你这些游戏都很受玩家喜爱而且很流行,但事实情况并非如此。玩家几乎需要在强迫的条件下才愿意接触游戏。

某些人在真正玩到游戏的时候感到惊讶。游戏有着色彩鲜艳且卡通化的艺术。但是《Monkeys on the Moon》却是款紧张且大脑负担较重的投标游戏。《The Nacho Incident》并不像前者那样紧张,但是依然是需要玩家思索的盲拍游戏。

玩家没有考虑过会看到这种类型的游戏。他们看到游戏的主题和展示,就下意识地将游戏划归简单的拾取类游戏。我的多数朋友已经远离此类游戏多年。

我强调“下意识”这个词有一定原因。我不认为自己的好友同我一样是个自命不凡的游戏玩家,但是我们都会下意识的过滤和处理信息。当游戏同期望存在偏差时,这正因为这种下意识在发挥作用。

我认为,这些游戏中存在的问题是主题机制超负荷的情况。主题与机制之间不对应,会使整款游戏受到影响。我相信,如果这两款游戏的主题变更为17世纪的地中海丝绸交易,再加上奢华的欧洲风格图像,无疑可以登上Boardgamegeek前200名游戏排行榜。

人们抱怨多数欧洲主题游戏的乏味,我必须承认,某些主题的游戏确实丝毫没有吸引人之处。

但是,那些乏味的主题有自身的目标,它们的目标就是不转移玩家的注意力。多数欧洲游戏吸引玩家的是游戏机制,而不是主题。

你玩《Puerto Rico》并不是为了寻求征服热带岛屿的那种快感,而是体验角色选择以及游戏中需要的深层次战术。你玩《Bohnanza》并不是为了体验种植庄稼的感,而是感受交易的完美平衡。你玩《Caylus》并不是为了体验建造城堡的感觉,而是体验其强迫你做出的苦恼选择。

这就好比我在作画,我手上只有颜色刺眼的彩色粉笔。我要如何展示前景或背景呢?我要如何引导观众的注意力呢?

起初,我认为无论游戏机制如何,游戏主题中都有表达艺术的空间。但是现在我发现,主题只是游戏机制的框架而已。你可以希望框架定义游戏,但是它最好不要夺走玩家对游戏本身的注意力。

对我来说,能够与机制融合在一起才是好主题,你无法注意到二者的分隔点。《Galaxy Trucker》便是个有这种主题的范例游戏。在这款游戏中,每回合的前半部分用来建造宇宙飞船,后半部分要努力保护其不被宇宙中存在的各种威胁炸成碎片。这确实很有趣,而且充满吸引力,你甚至在游戏过程中都不会感觉到自己正在驾驶的是用下水管道拼成的飞船。

《Thebes》的主题设置和执行也很棒。在这款游戏中,所有的玩家都是考古学家。他们在游戏的半数时间里调查研究5个古文明,另一半时间挖掘代表考古挖掘点的5个袋子。他们研究得越深,能够得到的东西也就越多。这很重要,因为袋子中财宝和垃圾的比例基本相同。因为财宝可以增加点数,而垃圾会被仍会袋子中,所以研究对于得分来说很重要。

我必须承认,我并非这款游戏的狂热粉丝。我也不讨厌它,但是我希望游戏能够让玩家对自己的命运有更多的掌控。但是游戏确实有着大量的粉丝,因为他们理解考古本身就带有大量的运气成分。你可能研究某个文明,随后在挖掘点花费数个星期的时间,找到的却都是垃圾。主题足够强大,使其克服了游戏中可能被许多玩家视为缺陷的设置。

最后,如果主题和游戏玩法能够紧密配合,你的游戏就可能获得成功。如果主题比游戏本身更为出色,人们会在学习游戏的过程中感到困惑和迷茫。如果主题过于平淡,一开始就不会吸引人们接触游戏。

游戏邦注:本文发稿于2008年12月2日,所涉时间、事件和数据均以此为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Game design mistakes 1: When your game’s theme and mechanisms meet, and it all comes out pastel

Gil

I have two related mistakes to kick off this series.

First, pay attention to where your theme meets your mechanics. Second, try not to have one draw attention from the other.

There are countless articles that discuss whether theme is more important than mechanics, or vice versa. That doesn’t really concern us here.

Instead, I want to focus on where the theme meets the mechanics, and whether they mesh gracefully.

One of my game designs, Wag the Wolf, fell into this problem. Wag is a game about media companies trying to advertise the end of the world. The planet may or may not be doomed, but you get points for being close, so don’t let a few inaccuracies stop you.

This sounds like a silly, rip-roaring theme. And it is a fun game. But it’s not fun the way you expect it to be fun. There’s no silly, boo-yah cardplay, like in a take-that game.

So I noticed new players enthusiastically sitting down to play Wag, and then being confused as they realized they were playing a different game than what they expected. There was a cognitive dissonance, and it wasn’t good.

Look at it another way. If I told you we were going to play a game about the stock market, would you expect a two-player pure-strategy perfect-information game like Go or Zertz?

Or if we were going to play a game about giant ninja mecha attacking pirate zombies with lasers, how would you feel if the game featured auctions and an innovative card drafting mechanism, but no way for you to actually attack another player?

Here’s another example. There’s a very good game out there now that’s not getting the recognition it deserves. It’s called Wealth of Nations.

Wealth of Nations. Look at that name and tell me what you think the game will be about. Obviously, it’ll hew close to Adam Smith’s masterpiece about economics. It’ll probably be set in colonial times, and feature the new American nation trying to balance its new economic system against the still-powerful British empire and the European powers. There’ll probably be quite a few fiddly little rules that’ll tie the game to its period.

But it’s not. Wealth of Nations is a fairly dry negotiation Euro. Oh sure, there are “nations,” but they’re all fictional, with flags that only resemble real ones.

Wealth of Nations is really a board game heavily influenced by the classic computer game M.U.L.E., which is an incredible accomplishment unto itself. But it has nothing to do with 18th century economics, although you could argue that it’s a very good lesson of supply and demand.

This means that Euro fans who should want to play the game avoid it at first, because they think it’s going to be an economic-based wargame that they won’t be interested in. And wargame fans who do want to play it turn out disappointed that the theme isn’t more historical.

Of course, people who finally sit down to play Wealth of Nations are rewarded by a rich game with a fantastic economic system. But the game has to fight an awful lot of preconceptions to get out onto the table.

So, that’s the first point. Your theme infers your mechanics. If they don’t meet where your players expect them to meet, they’ll get confused. And that’s confusion that you’re going to have to overcome before your game even starts.

But is there room to play here? Can a truly talented designer, an arteeste if you will, take a hairy, overblown theme, and turn it into a solid game?

One of my favorite designers, Jim Doherty, has a couple of games with absolutely absurd themes. Monkeys on the Moon is about advancing tribes of monkeys on the surface of the moon, and firing the most civilized by rocket back to Earth. The Nacho Incident is about smuggling black-market Mexican food into Canada.

I’d love to tell you how well-received and popular these games are, but they’re not. I have to almost twist peoples’ arms to play them.

A few people are surprised when they actually play the games. The games both come in small boxes, and feature silly, colorful, and cartoony artwork. But Monkeys on the Moon is a tight, brainburning bidding game. The Nacho Incident isn’t as heavy, but it’s still a thoughtful blind-bidding game with elegant mechanics.

Players don’t expect that. They look at the games’ theme and presentation, and subconsiously figure the game to be a silly take-that game. Most of my friends played their last games of Fluxx and Munchkin years ago, and they’d rather not play that sort of game anymore.

I emphasized the word “subconsiously” in that last paragraph for a reason. I don’t think my friends are overt game snobs (unlike me), but we all subconscously filter and process information. It’s that subconscious filter that is throwing these mental exceptions when games don’t match expectation.

I think what’s happened with these games is that there’s a theme-mechanic overload. One distracts from the other, and the whole game experience suffers. I’m absolutely convinced that if either Monkeys or Nacho was about Mediterranean silk trading in the 17th century, and it came with typically sumptuous Euro graphics and wooden bits, it would be in the top 200 at Boardgamegeek.

People complain about the blandness in theme of most Euros, and I have to admit, I find nothing appealing about the idea of bloodlessly colonizing an uninhabited, fertile land, or constructing the best cathedral to gain favor from some king.

But those bland themes have a purpose. Their purpose is to not draw attention. The draw of most Euros is the mechanisms, not the themes.

You don’t play Puerto Rico for the feel of colonizing a tropical island. You play it for the role selection, and the deep tactical implications that it entails. You don’t play Bohnanza for the feel of bean farming. You play it for the beautifully-balanced trading. You don’t play Caylus to feel like you’re building a castle. You play it for the agonizing choices the game forces you into.

It’s as if I was making a drawing, but all I had were loud pastel crayons. How do I indicate foreground or background? How do I direct my audience’s attention?

When I came into this hobby, I thought there was room for artistic expression in a game’s theme, no matter what the mechanics were. But I see now that your theme is just the frame for your game’s mechanisms. You want your frame to define your game, but you don’t want it to draw attention from the game itself.

To me, a theme is good when it blends with the mechanisms, and you can’t tell where one ends and the other begins. Galaxy Trucker is one example of a game that nails its theme. It’s a game in which you spend the first half of every round building a spaceship, and the second half trying to keep it from getting blown to pieces by various threats around the cosmos. It’s fun, it’s funny, it’s engaging, and at no point do you ever feel like you’re not flying around in a spaceship made of sewer pipes.

Another game with a well-implemented theme is Thebes. It’s a game where all players are archeologists. They spend half the game researching five ancient civilizations, and half the game digging through five bags that represent archeological dig sites. The more they’ve researched, the more pulls they get. This is important, because the bags are made up of treasure and worthless dirt, roughly half-and-half. Since treasure is worth points, but dirt right back to the bag, researching is important to guarantee points.

I’ll have to admit that I’m not a huge fan of this game. I don’t hate it, but I wish there was a little more control over your destiny. But the game has a lot of fans, because they understand that archeology has a lot of luck inherent in the business. You can research a civilization, spend weeks at the dig site, and keep finding dirt. The theme is strong enough that it overcomes what many players would see as a deficiency in the game.

Ultimately, your game hums if the theme and the gameplay meet in that proverbial “happy place.” If the theme outshines the game, people will be confused and distracted as they learn the game. If the theme is too bland, people won’t be attracted to the game in the first place. But playing a game that nails its theme is a pleasure unto itself. (Source: Fail Better)

上一篇:游戏设计师需考虑的10大重要决策

下一篇:独立游戏开发者需重视的10个要点

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号