分析文字编写对游戏设计的重要性

作者:Ben Kuchera

游戏文字内容的不幸遭遇在于,当文字不恰当时我们会指出这个问题,但是当文字设计精巧时我们却没有给予足够的褒奖。下面以《半条命2》为例。

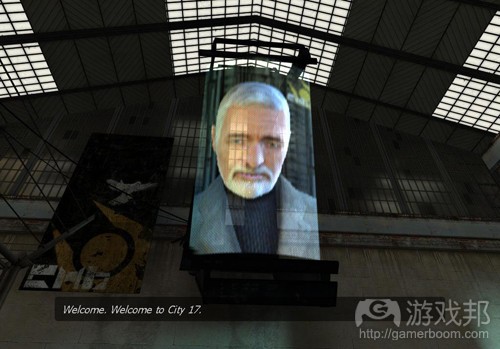

在游戏开始之时,你是一个还未进入城市废墟的普通市民。如果你是首次玩这款游戏的话,其图像和Source引擎可能会令你感到惊叹。确实非常漂亮。随后,建筑上的大屏幕会忽然跳出,Breen博士开始解释外星生物如何剥夺了我们繁殖的能力。这些文字的质量相当高,值得我们大篇幅地引用,如下所示:

让我看看刚刚收到的一封信。“Breen博士你好。为何Combine会影响到我们的生殖循环?——一个关心这个问题的市民。”

感谢这位表示关心的市民的来信。当然,你的问题触及的是最基本的生物学循环,体现了对种族未来的希望和焦虑心理。我也发现了某些潜在的问题。我们的捐助者是否真正明白什么才是对我们来说才是最好的?谁给予他们为人类做出此等决定的权利?将来他们能否解除抑制因素,让我们重新开始繁育生殖?

让我来解答你们焦虑背后潜藏的这些问题。首先,让我们认清一个事实,作为一个物种,这是首次我们可以实现永生的机会。这个看似简单的事实可能造成深远的影响。它需要我们进行彻底的反思,也需要我们对这种直接与神经学相冲突的事实制定适当的计划和预先的思考。

我发现,在这种时刻,提醒自己我们真正的敌人是本能是至关重要的。当我们这个物种还处在发展初期时,本能是我们的母亲。本能悉心照料着我们,在某些艰苦的岁月里保证了我们的安全。正是因为本能,我们首次开始用粗制的篝火烹制了食物,看到了映照在山洞墙上的影子。

但是,与本能密不可分的是他的阴暗面——迷信。本能必定伴随着某些毫无理性的冲动之举,但是今天我们清晰地认识到了其真正的本质。本能刚刚开始意识到了自己的相关问题,像被逼上绝路的野蛮人一样,只有血腥的战斗才能够结束这一切。

本能将会对我们这个物种造成毁灭性的伤害。本能告诉我们,未知是种威胁,而不是种机会。本能会秘密地迫使我们远离改变和发展。因而,本能必须被消除。它必须被彻头彻尾地打倒,建立人们最迫切地需要:繁殖。

我们应该感谢我们的捐助者,让我们可以摆脱这种压倒性的力量。他们给予了我们无法自行获得的力量,让我们能够克制这种冲动。他们给予了我们目标。他们让我们将目光转向宇宙中的星球。

我相信,我们完全掌控自身的那天终会出现。而这一天正逐渐来临了。

这个场景让我的后背一阵发凉。人类就像牲口一般,被聚集在一起,受到控制。这是种对人性丧失的可怕描述,我们甚至失去了创造新生命的能力。传达出这股寒气的并非图像,而是文字。

《半条命2》中有许多此类强大的场景,文字与科技的配合将这款游戏铸造成经典现代游戏。劣质的文字可能会让同样的游戏呈现出较差的质量。但是这款游戏所取得的成功也展现出了游戏文字普遍存在的弱势,让我们产生如下问题:为何我们不能看到更多拥有此类场景的游戏?问题究竟出在哪里?

为何游戏文字未受到重视

游戏文字未被严肃看待,其首要原因在于文字并不能转变成利润。销售榜上位于前列的游戏没有优秀的文字或吸引人的角色,其盈利效果还是很好。但是,作为钟情于游戏艺术性的人,我们关注的是让游戏发展得更好,而不仅仅是卖出更多的同类产品。强调文字和对话将会让市场上几乎每款游戏质量得到提升,即使是那些因其文学性而备受称赞的游戏(游戏邦注:如《Hotel Dusk》)与其他形式的媒介相比时,仍然可以看到其文字写作有提升的空间。

我们不可再轻视游戏中的文字,应当开始更多地关注文字的质量和情感冲击力。我们可曾因某款游戏在这个方向上的进步,或因为游戏中令人印象深刻的文字和角色而称赞某款游戏?销售排行榜上的游戏在文字方面并不精致,但是那些有着绝妙文字艺术性的游戏(游戏邦注:如《Beyond Good and Evil》、《冥界狂想曲》和《网络奇兵》)尽管很受部分玩家喜爱,但很少出现在销售榜单上。事实上,单纯从经济利益的角度来看,优秀的文字几乎可以被视为对游戏是不利的。

即便当游戏文案努力去编写高质量的情节时,但是他们最终得到的却不是丰厚的回报,其中的原因不言而喻。

游戏文案是极客

Ken Levine设计的《生化奇兵》是款使用Ayn Rand的作品来作为故事背景的游戏。Levine告诉MTV News道:“多数制作视频游戏的人都熟悉《指环王》和《异形》等故事,他们都读过相关书籍或看过相关电影。这些故事中自然有可取之处,但是你需要对其做出改变。”

这便是游戏编剧方面所面临的最大问题之一。想要制作游戏的人将大量的时间花在玩游戏上,通常是某些有着不断重复概念的老旧游戏。但是将大量业余时间花费在游戏上的玩家想要的却往往是多数游戏所缺乏的东西。

行业中仅有的4或5个有影响力的内容构成了封闭式系统数据,习惯于这种情况的文案作者也会形成相同的思维定势——都采用来自《星球大战》的战斗和对话风格。最佳的游戏(游戏邦注:从故事和概念的角度来说)往往来自于熟悉各种不同文化、影响力和文字内容的文案作者。

解决这个问题的答案说起来容易,做起来难,这和多数有价值的东西一样。文案作者需要跳出定势思维,需要阅读除科幻小说之外更多的内容,需要去看那些不涉及枪支的电影。看看其他的媒体形式,询问自己为何《Kubla Khan》依旧是首重要的诗歌,它对游戏艺术有何启迪作用。

我花在学习其他艺术形式上的时间越多,觉得自己也就越容易理解游戏及潜藏在它们背后的概念。比如,数个月前,在我于Dalí博物馆欣赏绘画作品时,我意识到超现实主义者在我们意识到自己属于整个群体之前便明白了这一点。Dalí理解有时通过间接的手段可以更好地呈现真相,因而他绘制了本世纪某些最为奇形怪状和引人入胜的作品。

文案所接触的影响因素越多,可以在游戏中运用的内容就会越多。整个游戏行业也会得到发展。

投资者目标与开发者相悖

这是个更为麻烦的问题。如果没有故事或角色的游戏可以卖得更好,那么注重盈利的投资者会考虑到这一点。他们会削减在这些与游戏盈利不相关的方面中的投入,使得利益最大化。从这部分人的观点来看,这是个很不错的交易,但是如果我们希望游戏富有人性化或者让玩家产生更好的感觉,又是金钱将我们的理想扼杀在襁褓之中。Warren Spector有些令人沮丧的言论:“你永远不知道我有多少次被告知‘只要做一款射击游戏即可’。有个发行商甚至告诉我,‘以后永远也别再提游戏的故事性’。”

换句话说,开发商的意思“回到正统的设计上,人们想要的只是把东西炸飞而已!”如果你没有按发行商认为可以提高销量的方式来制作游戏,也就是制作有着肤浅故事的射击游戏或可笑对话的战斗游戏,那么你就称不上团队中的高效成员。他们希望你制作的是他们能够靠某个截屏就可以售出的游戏。

我觉得,能够解决这个问题的惟一方法是尽可能地教育更多的玩家,让他们用自己手中的金钱为游戏投票。如果有着强大角色和文字的游戏开始大卖,人们终会认识到这种设计的益处。

虽然我们确实很关注游戏的这个层面,但是可能我们只占游戏购买者的一小部分。发行商想要提供的是大部分玩家想要的东西。或许这种情况令人沮丧,但我们需要承认许多人根本没有把游戏视为艺术形式,就像许多人只是将电影视为逃避现实的环境而已。

而且,游戏这个行业发展得越大,我们越容易看到这种情况的发生。需要环境声效和数十人团队参与的游戏系统只会让情况变得更加糟糕。如果你负责控制资金的分配,你会将更多资金投给设计枪支还是对话的人呢?猜猜哪个最能够影响游戏的销量?

幸运的是,局面并非完全无法挽回。游戏行业可以通过某些方法使得发展步入正轨。

正确的发展方向

文案应尽早介入项目开发

做到这点很简单,甚至不会花费许多资金。随着开发预算的增加,文案作者便会越来越容易被人们所忽略。如果你在开发首日便在团队中引进一个强大和负责任的文案,这比你在开发进行数个月后再考虑作者要好得多。

不幸的是,多数开发商并不这么想,他们认为可以在项目开发末期加入文案,结果依然会十分良好。事实上,最终结果将与这些开发商料想的相反。

虽然设计团队可以制作出基础概念,甚至是基本的故事情节,但是自项目首日起便考虑到文案终会让多数游戏受益。将文案作者视为过滤器,他会帮助审视从角色设计到建筑结构的所有事项,得出这些内容与游戏主题和信息的契合度。如果游戏所涉的每个人物都有强大的角色草稿,这一点也会对艺术师在决定角色所穿装备时有一定的益处。在项目设计之初有强大的对话,还可以使过场动画的设计更加容易,也能产生更大的影响力。

你可以基于枯躁的设计文件来制作游戏世界,但是预先拥有故事、角色甚至剧情能够帮助所有人根据现实世界构建游戏世界,让游戏世界中发生的事情更加栩栩如生。在最佳的脚本中,艺术应该能够激发作者创作出更好的作品,随后激发游戏产生更棒的艺术工作和资产。在制作过程中,应该形成上述良性循环,而可能实现的惟一方式便是尽早地考虑到文案。在团队中纳入文案作者,给他们一周的时间来进行创作,我们的收获将比现在的方式(游戏邦住:让故事削足适履地适应已经构建的游戏)要好得多。

电影导演方法

处理游戏文字和扩展游戏设计的最难方法之一是塑造推动整个项目的中心负责人。这可能会很困难,因为这个职位需要有大量经验的人来担当,当然也必须能够让那些投资者相信他的能力。《幻象杀手》的作者和制作总监David Cage谈到了这种方法的困难性:

负责原创项目是这个行业中最糟糕的情况,但也是最令人振奋的情况。因为在这个过程中你会受到大量的质疑。两年的时间里,你需要废寝忘食地将时间投入到项目中,同时还要当心想法不出现错误和可能产生的巨大风险。

这也是种相当有吸引力的体验,因为原创项目让你可以构建自己的愿景,测试自己的想法,在团队中体验到特别的职业化工作,烦恼和愉快的情绪会周期性地显现。

《幻象杀手》的情况就是如此。这次经历给了我很大的启示,强迫我考虑自己对这种媒介未来发展的愿景以及如何让其得到发展,有时需要保留某些有价值的东西,有时需要打破常规设计。

尽管《幻象杀手》最后的部分显得不尽完美,但是前半部分仍是最近最为引人入胜的游戏体验。Cage为游戏编写了逾2000页的设计和对话,确保每个场景和对话文字都与游戏整体相符。Cage直言了他想要如何制作游戏:

如此设计的目标在于在游戏制作中运用“电影导演”的方法,比如创作某个角色可以表达自己意愿的故事背景。这使得我们可以采用最佳的方案,而不用频繁地区寻找折中方案,因为后者会对创新型项目造成毁灭性的伤害。

对于我来说,项目愿景中使用上述做法是基本的要求,真正的原创游戏很少缺乏个人的创造性愿景。

所有钟爱于游戏中的文字叙述的人都知道Tim Schafer。在采访中,他讨论了他在行业中的首份工作,那就是同LucasArts合作,他讲自己的工作称为“半创造性写作和半编程”。现已证实,这个背景对他的游戏设计风格来说弥足珍贵。在2003年的采访中,Schaefer说过这个背景让他可以在编写文本时进行程序性的思维。Schafer告诉Game Studies说:“我的意思是,如果编写内容和编程分别由两个人来负责,这种设计方法便很难实现。因为我从不在文本程序中编写对话。我用SCUMM或其他语言将对话直接编入代码中。”

这种思考方式和领导角色在其他的艺术形式中很常见,但是游戏更多采用的是团队写作的方法。现在我们已经看到开发商对游戏文字提起重视,这是个不错的现象。

虽然我们行业中的许多人希望游戏随主流发展,但是有如此多的用户支持,故事元素肯定不会在行业中退居二线。令故事粉丝感到幸运的是,我们有许多注重这个层面的游戏,如《半条命2》等。现在已经有优秀的此类游戏,作为粉丝,我们的工作就是尽所能提供支持。

游戏邦注:原文发表于2007年,所涉时间以当时为准(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Why writing in games matters: Part I? Advancing the art of storytelling

Ben Kuchera

A scarce commodity

The problem with writing in games is that we point out when it’s terrible, but we don’t praise it enough when it’s good. Consider Half-Life 2.

In the beginning of the game, you’re just another desperate citizen pushed through processing before entering the city. People around you are muttering, and if this is your first time playing, you’ll likely amazed by the graphics and the Source engine. It’s beautiful. Then the megascreen on the building pops up and Dr. Breen appears to explain why the aliens have taken away our ability to reproduce. The quality of the writing makes it worth quoting at length:

Let me read a letter I recently received. “Dear Dr. Breen. Why has the Combine seen fit to suppress our reproductive cycle? Sincerely, A Concerned Citizen.”

Thank you for writing, Concerned. Of course your question touches on one of the basic biological impulses, with all its associated hopes and fears for the future of the species. I also detect some unspoken questions. Do our benefactors really know what’s best for us? What gives them the right to make this kind of decision for mankind? Will they ever deactivate the suppression field and let us breed again?

Allow me to address the anxieties underlying your concerns, rather than try to answer every possible question you might have left unvoiced. First, let us consider the fact that for the first time ever, as a species, immortality is in our reach. This simple fact has far-reaching implications. It requires radical rethinking and revision of our genetic imperatives. It also requires planning and forethought that run in direct opposition to our neural pre-sets.

I find it helpful at times like these to remind myself that our true enemy is Instinct. Instinct was our mother when we were an infant species. Instinct coddled us and kept us safe in those hardscrabble years when we hardened our sticks and cooked our first meals above a meager fire and started at the shadows that leapt upon the cavern’s walls.

But inseparable from Instinct is its dark twin, Superstition. Instinct is inextricably bound to unreasoning impulses, and today we clearly see its true nature. Instinct has just become aware of its irrelevance, and like a cornered beast, it will not go down without a bloody fight.

Instinct would inflict a fatal injury on our species. Instinct creates its own oppressors, and bids us rise up against them. Instinct tells us that the unknown is a threat, rather than an opportunity. Instinct slyly and covertly compels us away from change and progress. Instinct, therefore, must be expunged. It must be fought tooth and nail, beginning with the basest of human urges: The urge to reproduce.

We should thank our benefactors for giving us respite from this overpowering force. They have thrown a switch and exorcised our demons in a single stroke. They have given us the strength we never could have summoned to overcome this compulsion. They have given us purpose. They have turned our eyes toward the stars.

Let me assure you that the suppressing field will be shut off on the day that we have mastered ourselves…the day we can prove we no longer need it. And that day of transformation, I have it on good authority, is close at hand.

This scene sent chills down my spine. The human race has become a collection of cattle, shoved into the ghettos to be controlled and handled. It was a terrifying portrait of lost humanity; we didn’t even have the ability to create new life. That chill I felt wasn’t created by the graphics: the writing did it.

Half-Life 2 is loaded with powerful moments like this, and the writing worked with the technology to make the game a modern classic. Bad writing could have turned the same game into a B-novel of the ripest variety. But the very success of the game points up the weakness of game writing in general, and it begs the question: why don’t we have more examples of scenes like this? What, exactly, is the problem?

This week, we’ll take a look at the problem. Next week, we’ll talk to someone who’s part of the solution: Susan O’Connor, writer on titles like Gears of War and Bioshock.

Why writing isn’t taken seriously

The number one reason writing isn’t taken more seriously in gaming is that writing doesn’t translate into dollars. Top-selling games do fine without good writing or compelling characters. As fans of the art of gaming, though, we’re concerned with making games better, not just selling more copies. Emphasizing words and dialogue would raise the quality of almost every game on the market; even games lauded for being literary, like Hotel Dusk, usually have subpar writing when compared to any other medium.

We’re so starved for writing that when we’re thrown a bone with a few scraps on it, we treat it like steak. We need to stop going gaga over games that are simply wordy and start caring more about quality and emotional impact. Do we praise a game because it’s a step in the right direction or because memorable lines and characters populate its world? Sales chart routinely show games with barely passable writing in the top ten, while games with excellent writing—Beyond Good and Evil, Grim Fandango, System Shock—become critical favorites but rarely make the charts. In fact, from a purely financial perspective, good writing can seem almost detrimental.

Even when the writers try to turn out a quality plot, they often end up with nothing more than a steaming pile of clichés and a few cardboard characters. The reason isn’t hard to find.

We write what we know. And we are geeks

Ken Levine is designing Bioshock, a game that draws on the work of Ayn Rand for its story and setting. He may be painting in broad strokes here, but his brutal take on game writers has the ring of truth to it. “Most video game people have read one book and seen one movie in their life, which is Lord of the Rings and Aliens or variations of that,” Levine told MTV News, adding, “There’s great things in that, but you need some variety.”

This is one of the biggest problems in game writing. People that want to make games spend much of their time playing games, usually old-school titles that feature mostly subpar writing and a handful of rehashed concepts. But gamers who spend most of their free time playing games are going to be hard-pressed to draw on the wide set of cultural touchstones needed to give your title the resonance and weight that most games lack.

When writers feed into a closed system (their minds) data that comes from an industry that draws from the same four or five influences, the same attitude and set of clichés are going to pop right back out: bullet time and barbarians, force fields and regurgitated dialogue from Star Wars. The best games (in terms of story and concepts) come from people who allow themselves to become immersed in different cultures, influences, and writers.

The answer to this problem is easy to say and hard to do, like most things worthwhile. Writers need to get out more, need to read more than science fiction, and need to watch movies that don’t involve guns. Go watch a good romantic comedy and ask yourself how you could turn it into a game. Look up some Coleridge and ask yourself why “Kubla Khan” is still an important poem, and what it suggests for the art of gaming.

The more time I spend learning about other kinds of art, the more I feel like I can understand games and the concepts behind them. One example: a few months ago I was standing in the Dalí museum looking at paintings, and I realized that the surrealist was painting gamers before we even knew who we were as a group. Dalí understood that truths sometimes work best when presented indirectly or through the lens of a fantastic vision, and he went about constructing some of the most bizarre and intriguing images of the century. Game designers looking to create alternate worlds of their own could do worse than look to Dalí for guidance.

The wider the influences, the more that a writer can bring to the table. The industry will be better for it.

The money men are against you

Here’s a more difficult problem. If a game sells well without story or characters, then the money men did their jobs. They cut off spending to an area of a game that wasn’t needed to get those sales, and that helps the profit margin. From the point of the view of the shareholders this is a good tradeoff, but if we want something approaching humanity or feeling in our games, this is just another case of money strangling us almost as we draw our first breath. Warren Spector has some depressing words for us in this area: “You don’t want to know how many projects I’ve been told to ‘just go make a shooter’. I had one publisher tell me ‘you’re not allowed to say “story” any more.”

In other words, “Get back to work; people just want to blow stuff up!” If you’re not working on what the publishers know will sell—and that’s shooters with shallow stories or fighting games with laughable dialogue—you’re not an efficient member of the team. They want you working on things that they can sell in a screenshot, tell to the press, and put as a bullet point on the back of the box. Deformable environments get coverage in the gaming press; strong story does not. From every objective angle it’s not a good investment.

The only way I can think to fix this problem is to educate as many gamers as possible and get them to vote with their cash. If games with strong characters and evocative writing start to sell, the right people will notice.

While there are those of us who do care about such things, though, it may be that we’re the small minority of the game-buying public. It could be that the publishers really are providing the majority what it wants. This may be a depressing picture, but we need to accept that many people won’t ever view games as art, much as many people only see films as escapist entertainment.

And the bigger gaming gets as an industry, the more we’ll see this happening. High-definition systems that require surround sound and teams of dozens, if not hundreds, of people are only going to make this worse. If you control the purse strings, do you want someone designing a new gun, or the dialogue? Guess which one will most affect your sales?

Fortunately, it’s not quite a lost cause. There are a few ways that the industry can make things right.

Making it right

Bring writers in earlier

This is easy and not even that expensive. As development budgets increase, it will get even be easier to “sneak” a writer in than it was when people tried to release games for the smallest initial investment. If you have a strong, able writer involved in your game from day one to shipping, you stand a better-than-average shot at having something that feels cohesive than if you bring in a writer a few months before launch.

Unfortunately, most developers don’t think that way, believing that you can drop a writer in at the end of a project and everything will turn out just fine. It doesn’t, and the end result is something akin to putting Neal Stephenson to work writing classified ad copy for your local alternative weekly newspaper.

While the design team can come up with basic concepts and even a bare-bones story for the game, having a writer there from the first day on would be a huge benefit to most games. Think of the writer as a filter: (s)he can look at everything from character design to building structure and figure out how it fits with the theme and message of the game. Having a strong character sketch for each person in the game would also help artists work on things that are more meaningful than what kind of armor they will wear. Having strong dialogue from the jump would allow cut-scenes and cinematics to be more easily directed and to have more impact.

You can make a game world based on a dry design document, but having the story, character, and even plot done ahead of time will allow everyone to do actual world building and infuse the experience with life and color instead of simply making “dystopian future earth #294.” In the best-case scenario, the art should inspire the writer to do better work, which then inspires better artwork and assets. It should be a circular give-and-take between the team throughout production, and the only way that’s possible is by having a writer involved as early as possible. Bringing a writer onto a team and giving them a week to do the job will just give us more of what we’re stuck with now: stories shoe-horned into games that weren’t built for them.

The auteur approach

One of the harder ways to handle game writing—and by extension game design—is to have one central personality who drives the entire project. This can be tough simply because it takes a lot of time to have the level of experience needed to step into that sort of role, and of course someone with money must trust you before they hand over the reins to your own game. David Cage, the writer and director of Indigo Prophecy, talks about the difficulty of having such control:

Working on an original project is both the worst curse and the most exciting thing that can happen in this industry. It’s a curse because you go through periods of terrifying doubt. For two years you abandon all notions of a private life and forgo many hours of sleep because you are permanently looking for the right path, being simultaneously haunted by the idea that you may be completely mistaken and may be taking enormous risks.

It’s also a fascinating experience because an original project allows you to construct your own vision, to test your convictions on the ground, to experience an extraordinary professional and human adventure with a team, with all the alternating periods of torment and euphoria that this implies.

Indigo Prophecy was all of that. This adventure taught me an enormous amount of things by forcing me to think about my vision of the future of this medium and how to make it evolve, sometimes by remaining true to its still-young traditions and sometimes by breaking away from them.

While Indigo Prophecy broke apart in the final acts, the first half remains one of the most engrossing gaming experiences in recent memory. Mr. Cage wrote over 2,000 pages of design and dialogue for the game, ensuring that every scene and line worked with the larger whole. Cage is candid about how he wanted to make the game.

The purpose of this organization was to have an “auteur” approach to game creation, i.e. to create a context that gives one person full power to express his/her vision. This specifically made it possible to adopt strong-willed stances without constantly seeking compromises at all costs, which would have been disastrous for a project that claims to be innovative.

For me it is fundamental to have the director embodying the vision of the project: it is extremely rare for a truly original game to be developed without the creative vision of one person (from Shadow of the Colossus by Fumito Ueda to Psychonauts by Tim Schafer or Killer 7 by Gouichi Suda, or also Metal Gear Solid by Hideo Kojima).

Tim Schafer, who is named by everyone who enjoys good writing in games, also wears more than one hat when working on a game. In interviews he discusses his first job in the industry, which was with LucasArts, calling it “half creative writing and half programming.” That background proved to be important for his style of game design. In a 2003 interview, Schaefer commented on how coming from a cross-disciplinary background provided him with a procedural way of thinking when it came to writing. “I mean it would be really hard to do if one person was doing the writing and one person was doing the programming,” Schafer told Game Studies. “Because I’ve never written my dialog in a script program. I’ve always written it in SCUMM, or whatever language—into the code itself.”

This sort of thinking and leadership role is common in other art forms, but gaming more often features a team approach. It’s clear why inflectional games often have an outspoken and strong-willed name behind them. We’re seeing personalities start to emerge that are able to work within the boundaries of the business and improve the state of game writing—a good thing.

While many of us wanted gaming to go mainstream, it was hard to imagine that with a broader audience story would take a back seat—the Michael Bay effect, in other words. Luckily for fans of story, we get enough games like Bully, Psychonauts, Half-Life 2, and Beyond Good and Evil to keep us hopeful for the future. Good writing is out there, and it’s our job as fans to make sure we support it as much as we can.

Next week we’ll hear from professional game writer Susan O’Connor, whose writing credits include Gears of War and Bioshock. Susan talked with Ars about words, her love for Guitar Hero, and the misery of having an actor butcher a line you’ve written. (Source: Ars Technica)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号