游戏设计课程之决策和“心流”理论(7)

能谈这个话题让我非常兴奋,因为我们将接触到游戏设计的实质——决策和乐趣的性质。这些是我都喜欢讨论的主题,因为这是关于玩家与系统之间的交互活动,而正是交互性才将游戏与其他传统媒体区别开来。这是游戏的魔法,当制作游戏时,这道魔法总是在我的心中闪现火花。(请点击此处阅读本系列第1、第2、第3、第4、第5、第6、第8、第9、第10、第11、第12、第13、第14、第15、第16、第17、第18课程内容)

决策

Costikyan在《I Have No Words》中指出,我们用这个热门词“交互性”形容我们真正所指的“决策”。所谓“决策”,本质上是指玩家在游戏中的所做所为。如果没有这些决策,那么游戏就不再是游戏了,只不过是电影或其他线性活动罢了。完全不具有“决策”的游戏主要有两个例外:某些儿童游戏和赌博。关于赌博,没有决策是合情理的。赌博的“乐趣”在于可能赢钱也可能输钱的刺激感;如果没有这种刺激感,那么大多数赌博瞬间失去所有乐趣。在家筹码玩赌博游戏时,你玩的扑克牌包含了真正的决策成份;如果跟钱无关,可能也没什么人会去玩掷骰子或老虎机了。

你可能会好奇,儿童游戏完全缺乏决策是怎么回事?我们就稍微谈谈吧。

除了那两个例外,大多数游戏都有一定的决策方式,且游戏的乐趣会因此受到或多或少的影响。Sid Meier曾表示,好游戏就是一系列有趣的决策(大概就是这个意思吧)。这个观点有一定道理。但什么能让决策“有趣”?《战舰》是一款包含大量决策的游戏,但对成年人来说,不算特别有趣,为什么呢?为什么《卡坦岛》中的决策比《大富翁》中的更有趣?最重要的是,怎么给你自己的游戏设计出真正吸引人的决策?

禁忌

在描述什么是好决策以前,我们有必要先认识一些不太有趣的决策。注意,下面用到的术语(明显的、无意义的、盲目的)是我自己想的,不是行话,至少目前还没有“官方”承认。

无意义的决策大约是最糟糕的一种:玩家有选择可做,但对游戏玩法不产生影响。如果玩家出哪张牌都一样,那也不算存在选择吧。

明显的决策至少对游戏有所影响,但如果正确答案太过赤裸裸,其实也不算有选择。在桌面游戏《RISK》中的掷骰子就属于这一类:如果你受到3名或以上的敌人攻击,你可以“决定”是否掷骰子1次、2次或3次……,但最好的显然是3次,所以除了非常特定的情况,其实没有多少决策可做。《Trivial Pursuit》中有一个更微妙的例子。每一回合,玩家将面对一道很琐碎的问题,

如果知道正确答案,那么你就要决策了:说出正确答案或不说出来。如果玩家知道答案,凭什么不说出来呢?游戏的乐趣就是向别人展示你对生活中的鸡毛蒜皮之事多么了如指掌,而不是掌握了一套高明的决策技巧。我认为,这也是为什么《Jeopardy!》这种问答秀节目看着比玩着更有意思。

盲目的决策对游戏有影响,答案也是不明显的,但存在另一个问题:玩家没有足够的知识信息做决策,所以只能随机做决定。“石头-剪子-布”游戏就属于这一类。你的选择会影响游戏结果,但你没有办法有根有据地决策。

以上决策,很大程度上,并没有多少乐趣,至少不算特别有趣,基本上是在浪费玩家的时间。无意义的决策可以删除;明显的决策应该自动实现;盲目的决策可以随机化,且完全不必对游戏的结果产生影响。

现在看来,我们很容易就明白为什么那么多游戏并不是特别吸引人。

想一想这款通俗问答游戏《Trivial Pursuit》。首先,你把骰子投向任意方向,所以你要落在哪里就构成了一个决策。在游戏面板上,有助于取胜的空间并不大,所以你要尽可能落在其中,这是一个明显的决策。如果你不能,你的选择一般就取决于你最擅长的那个问题分类,这又是一个显然的(游戏邦注:或盲目的,在做出选择以前,一定程度上你并不知道你在各个分类中会遇到什么问题)决策。一旦骰子停下来,你的琐碎问题就出来了。如果你不知道答案,那就没什么决策可言了;如果你知道正确答案,那么你要决策的就是说出来还是不说出来……但没理由不说啊,所以这又是一个明显的决策。

再来考虑一下我们老提到的桌面游戏《战舰》。这款游戏的所有决策都是盲目的。游戏没有给你任何决策信息,所以你不知道向哪开火。如果你恰好击中敌方的潜艇,你确实有了一些信息,但你仍然不知道战舰的方向(横向或纵向),所以玩家的下一次决策仍是勉强的,只是盲目的成分稍策少了一点罢了。

《Tic-Tac-Toe》这款游戏有些有趣的策略,不过,那是在你掌握游戏和意识到百战百胜的方法以前。之后,所有决策也将变得显而易见。

好决策?

既然我们知道什么是“坏决策”了,那么要回答什么是“好决策”也简单了。不过,我们还要再深入一点。一般来说,有趣的决策与交易有关。也就是,你得有所放弃才能有所收获。这种交易可以有多种不同的形式。以下我列举了一些例子(我用的仍然是我自创的术语):

资源交易:你放弃一种以换取另一种,且二者皆有价值。哪一个更有价值?这是一个价值判断,玩家的能力是否能正确判断或预期价值决定了游戏的结果。

风险与回报:一种选择是安全的;另一种选择可能有更高的回报,但也有更高的风险。你选择安全的那个还是危险的那个?部分取决于你对回报的渴望程度,另一分部取决于你对安全和风险的分析。你的选择,再加上一点儿运气,决定了结果。但因为选择的数量是相当充足的,所以运气的成分影响不大,获胜的往往还是技巧是更胜一筹的玩家。(推论:如果你想在游戏中增加运气的份量,最好的办法就减少决策的整体数量。)

行动的选择:你有若干你可以做的事,但你不能同时全都做。玩家必须选择自己觉得最重要的事做。

长期与短期:你有些事必须马上做,或者稍后再做。玩家必须平衡当即需要与长期目标。

社交信息:在游戏的世界中,欺骗、交易和背后中伤都是充许的,玩家必须在诚信与欺诈中作出选择。欺诈可能在当前境况下有利可图,但导致其他玩家以后都不想跟你交易。暗箭伤人可能会在现实世界里产生消极结果。

两难困境:鱼和熊掌不可兼得,你能承受损失哪一个?

注意这里的共同思路。所有这些决策都涉及玩家对事物的价值判断,价值总是在转移并且不总是肯定的或明显的。

下次你玩一款确实喜欢的游戏时,注意一下你在做哪一种决策。如果你有什么特别不喜欢的游戏,就思考一下你在游戏中做的是什么决策。你会发现自己在游戏中的决策偏好。

动作游戏?

这会儿,你大概想知道,以上有多少条可以用于FPS游戏?毕竟,当身处枪林弹雨之中,小命都快顾不上了,谁还能想到权衡资源管理什么的呢?

简单地说,此时玩家在游戏中做的也是相当有趣的决策,且实际上决策的速度比平时快得多——通常每秒钟就要决策几次。为了缓和时间紧凑带来的难度,此时的决策往往是相当简单的:开火或躲避?命中或移动?闪避或跳跃?

时限可以用来把一个明鲜的决策变成有意义的决策。我个人偏好的另一个说法是:时限让人变傻。

情绪决策

还有一类决策有必要考虑一下:能影响玩家情绪的决策。在《Far Cry》中, 是救同伴(使用你宝贵的资源)还是让他自生自灭,这是一种资源决策,但也是情感决策——这与现实战场上的决策一样,但现实中还要分析可用的资源和可能性。与此类似,绝大多数玩家不会带着“道德选择就是有害的”这样的想法来玩游戏(《Knights of the Old Republic》或《神鬼寓言》)——不是因为“有害的”是次等策略,而是因为即使是在虚拟的世界中,许多人也不能无动于衷地看着无辜者被拷打或残杀。

再来思考一下许多桌面游戏的开头部分普遍存在的决策:己方是什么颜色?颜色通常只是为了区分面板上属于不同玩家的对象而设置的,对游戏玩法本身并无影响。然而,不少人都有自己最中意的颜色,玩游戏时总是坚持使用“自己的”颜色。如果两位玩家都“总是”玩绿色,碰上了免不了要为谁用绿色而争吵不休,那就有意思了。如果玩家的颜色对游戏玩法无影响,这就是一个毫无意义的决策。然而事实上,玩家却矛盾地发现这种决策还是有意义的。理由是,玩家对结果有一种情绪上的寄托。当然,作为设计师,应该意识到玩家会在情绪的影响下做出什么样的决策。

“心流”理论

我们来讨论一下这个难懂的概念“乐趣”。游戏应该有乐趣。游戏设计师的作用大多数时候就是让游戏变得有趣。请注意,当我提到“乐趣”一词时,我总是故意把它带上引号,因为我认为这个词对游戏设计师来说并不特别有用。我们天生就知道什么是有“乐趣”,这是肯定的。但这个词没有向我透露过应该怎么制作“乐趣”。什么是“乐趣”?“乐趣”从哪来?什么让游戏有“乐趣”?

有趣的决策看起来好像应该有“乐趣”。是这样吗?不见得,为什么这类决策是有趣的,或为什么不有趣的决策对孩子们来说仍然有趣,对这些问题我们还没有解答。所以我们来看看Raph Koster怎么说的吧。

Raph Koster的《Theory of Fun》是这么说的:游戏的乐趣来自技能的掌握。真是激进的论断呢,因为这个说法把“乐趣”与“学习”给等量齐观了……至少我没长大时,我总是习惯性地把“学习”与“学校”挂钩,“学校”当然没什么“乐趣”可言。所以,这个理论有必要稍作解释。

《Theory of Fun》大量提到心理学家Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi的研究成果,即情绪的“心流”(flow)状态。当人处于这个状态时,将会对着某事物全神贯注,心无旁骛,效率也会非常高,另外你的大脑会产生一种使你愉悦的神经化学物质——“心流状态”只是书面上的说法。

Csikszentmihalyi认为达到“心流”状态必须具备3个要求:

1、你所处的活动具备挑战性,需要一定技能;

2、活动有明确的目标和反馈;

3、结果是不确定的或受到你的行为的影响。(游戏邦注:Csikszentmihalyi称之为“控制的悖论”:你能控制自己的行为,从而间接控制结果,但你不能直接控制结果)以上要求是有道理的。为什么你的大脑需用排除所有外界干扰,精神高度集中于眼下的活动才能进入“心流”状态?因为只有这样,你才能完成任务。“心流”状态影响成败需要什么条件?

你必须有能力用自己的技能(针对目标)影响活动。

Csikszentmihalyi还提出了“心流”状态的5个效果:

1、行动与意识的融合:自发的、自动的行动/反应。换而言之,你是自然而然地做事,头脑根本不用想。(事实上你的大脑运转得比思考得更快——当你玩《俄罗斯方块》达到“心流”状态时,如果突然想到要保持这种最佳状态,就这么稍稍走神,砖块似乎落得更快了,结果你输了。我就是这样。)

2、全神贯注于当即任务:完全集中注意力,没有半点分心。你不会考虑其他任何任务;你想的是当下,只有当下。

3、达到忘我的境界。当你处于“心流”状态时,你不再是单独的你,而是与周围的一切融为一体。(这里有点禅意)

4、对时间的曲解。奇怪的是,这点有两层意思。有些时候,比如我说的《俄罗斯方块》的例子,时间好像变慢了,事物看似在慢速运动。(其实是你的大脑在高速运转,而万物的速度并没有变化,你是以自己作为参照物看待周围的一切)也有些时候,时间好像过得更快了。比如你本来打算只玩五分钟,可是六个小时后,你才醒悟过来:一整晚都耗在游戏上了。

5、活动的体验本身就是目标:为了活动体验的本身而活动,与任何外在的奖励无关。另外,你不会想到更长远的目标,你关注的就是“此时此地”。

我发现比较搞笑的地方,当小孩子不好好读书,而是沉溺于玩游戏时,其父母会抱怨他们“走神”。事实上,玩游戏的小孩子就处于“心流”状态,精神可谓达到高度集中。

游戏中的“心流”状态

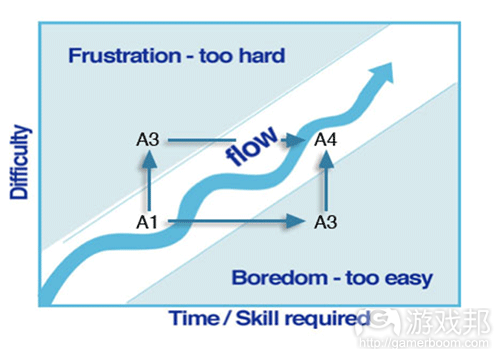

简而言之,我们知道,能让人处于“心流”状态的活动必须是有挑战性的。如果任务太简单了,大脑就不会再浪费额外的精力了,因为结果已经有保障了。如果任务太难了,大脑也没必要再努力了,因为失败是尽早的事。这里的目标必须是努力之后就能达到的。你可以参考下面这幅图:

如果你的技能水平高,但任务太简单,你就会感到厌烦;如果你的技能水平低,任务却太难,你就会受挫;但如果活动的挑战水平与你当前的技能水平相当,那么你就能达到“心流”状态。

这对游戏来说很有意义,因为这是很多游戏的乐趣来源。

注意,所谓的“心流”状态与“乐趣”不是近义词,尽管二者存在联系。你没有玩游戏时(甚至在做并不有趣的事)也可能处于“心流”状态。比如,一个办公人员填写表格时也可能陷入“心流”状态,所以填起表来非常快,但他们可能并没有在学习什么,这个过程也并不有趣,只是沉思罢了。

一点小问题

当你面对一个颇有挑战性的任务时,你会越做越好。之所以有趣是因为你正在学习,记得吧?所以,大多数人得从低技能水平开始进行某项活动(如游戏),如果游戏一开始给予的任务比较简单,那很好。但如果玩家学会了一定的技能以后呢?如果游戏还是只给简单的任务,那么游戏就无聊了。《Tic-Tac-Toe》游戏就是这样让孩子慢慢失去兴趣的。

顺便一提,我们现在可以回答之前的问题了:什么儿童游戏中缺乏有意义的决策却仍然被视作有乐趣呢?答案是,儿童仍然在从游戏中学到有价值的技能:怎么掷骰子,怎么移动面板上的标记物,怎么转向,怎么阅读/遵守规则,怎么决定输赢等等。这些技能不是生来就会的,而必须通过重复的游戏来教授和学习。当儿童掌握了这些技能,这款没有什么决策性的游戏也就失去其乐趣。

理想地来说,作为游戏设计师,你当然是希望你的游戏比《Tic-Tac-Toe》的寿命更长。那么该怎么做呢?以下是解决方案列举:

*随着游戏进程增加难度(我们有时也称之为游戏的“节奏”)。随着玩家的进步,玩家慢慢地进入游戏中更困难的关卡或区域。这在关卡类游戏中普遍存在。

*难度级数或障碍。比较有经验的玩家可以选择更困难的挑战。

*动态难度调整(简称DDA)。这是一种消极反馈环路,即游戏根据玩家的表现调整游戏自身的难度。

*玩家作对手。这当然可以让游戏更好玩,但如果你的对手也在进步,那么游戏仍然保持相同的挑战性(如果游戏的深度够的话)。(如果玩家之间的水平相差悬殊,这个方法就无效了。我喜欢跟我老婆一起玩游戏,一开始我们的旗鼓相当,但过了阵子,因为其中一方玩得时间更多,技术比另一方更好了,两人之间终于打不起来了。)

*玩家自创挑战。如玩家利用自己的关卡编辑工具制作新关卡。

*理解的多层次(许多策略游戏追求“一时学,一生用”的东西)。你可以几分钟就学会象棋,因为只有六种不同的棋子……但一旦你撑握了,你就开始知道不同的情况用什么棋子最有效最管用;然后你开始看到棋子、时机和区域控制之间的联系;再然后你可以研究著名的棋阵……

Jenova Chen的《flow》认为应当允许玩家在游戏中根据自己的行动改变难度级数。你厌烦了?那就上调一点难度吧,这样动作就更快了。你受不了了?那就调回刚才的难度吧(如果有必要,游戏会自动把你踢回更简单的难度级数)。

你可以注意到,当我们看到评论说某游戏具有“重玩性”或“可以玩上好几个小时”,其实是说该游戏特别擅长通过调整自身的难度来适应我们不断进步的表现,从而把不断地我们留在“心流”状态。

为什么玩游戏?

你可能会疑惑,如果“心流”状态这么令人愉悦,并且就是复杂而神秘的“乐趣”来源,那么为什么我们设计的是游戏而不是其他媒体?为什么不设计一种能触发“心流”状态的任务,让成千上万的人去为发现治疗癌症的验方而努力工作,而不是沉迷于《魔兽》?为什么不设计一种能触发“心流”状态的大学课堂,那样学生就可以坚持每周学习50小时,而不是好几周都难得看书几分钟。

游戏天生就擅长把玩家引入“心流”状态,所以设计一款有趣的游戏显然比设计一门课程来得容易。正如Koster在《A Theory of Fun》中所指出的,大脑是一种特征匹配机器,当我们的大脑处于“心流”状态时,就是在寻找和理解当前出现的特征。我认为游戏在这方面做得相当棒,因为你有三个层面上的特征:审美、动态识别和最终的机制精通。因为所有游戏都具备这三个层次的特征,所以游戏的乐趣是大多数其他活动的三倍。

“寓教于乐”游戏

你可能会想,如果游戏那么擅长教授,学习也那么愉悦,那么“寓教于乐”游戏不是乐疯了?事实上,“寓教于乐”是个我们非常不情愿提起的词,因为但凡标榜自己是“学中玩,玩中学!”的游戏,实际上二者皆失。那到底是为什么呢?

许多“寓教于乐”游戏是这么运作的:你进入游戏,一开始还有点玩头。接着游戏停下不动了,而是跟你灌输一些令人作呕的大道理。听完说教的奖励就是得以继续玩游戏。游戏玩法被设置成了学习实质上非常不好玩的任务的奖励。

我认为这种游戏设计的思路一开始就是错误的,所谓“上梁不正下梁歪”,按这种思路做出来的游戏必然没有什么价值。这种思路错就错在把“学习”和“乐趣”分离开了,我们知道,此二者不是单独的概念,而是统一的整体(或至少存在非常紧密的联系)。学习无乐趣,玩乐不教育的假想直接损害了整个游戏,也顺带强化了这个极其有害的概念,即教育即受罪,乐趣无处寻。

如果我们可以停止告诉孩子们“上学不是让你玩的”,那就太好了。如果我不用一开始就劝服学生相信他们在课堂上应该由衷地好好表现,那肯定会让我们当老师的日子好过得多。

那么,如果你想设计一款针对教学的游戏,怎么办?这个话题本身就值得专门开一堂课来讨论了。我的回答简要地说就是,首先将学习技能本身固有的乐趣分离出来,然后将其作为游戏的核心机制。通过综合学习和游戏玩法(而不是将二者作为孤立的概念或活动),你就离所谓的“玩中学,学中玩”的游戏近了一大步了。

提醒老师们

如果到目前为止你对上文没有异议,那么你也许看到了教学与玩乐之间的并行可能。如果学习本身是有趣的,那么你要怎么把乐趣从学科中引出来?

学生做的决策有多少是有趣的?我曾看过一个数据表明,大学生平均十周才在课堂上举手一次——也就是说,每年只有三次有意义的决策!你能做得更好一点吗?考虑一下,布置一个作业(加入交易的成分,如简单但无聊的作业或困难但有趣的作业)。在课堂上问一些跟学生自身有关的问题,进行课堂讨论或辨论。

是不是有很多学生因为你的课难度太高或太低而受不了?游戏也存在这个问题。游戏对此的解决方式是加入多重难度级数;对付教学的话,可以考虑采用一种分级系统,这种系统对学习比较差的学生而言,只要能学会基础知识,那就应该能够通过,而学习优秀的学生就可以做更有趣的额外作业。把课堂内容分层次,第一层是非常基础的、每个人都会的“傻瓜层”,然后增加确实重要的主要细节,最后给出只有某些学生才可能理解的内容,但那些内容的有趣程度必须至少能让学生有动机学习一点儿。

最有趣的游戏以玩家为中心,关注的首先是为玩家提供高品质的游戏体验。你可以感觉得出来,设计师在一款游戏的哪里制作出了他们想玩的地方,因为它卖了整整五份给设计师、设计师最好的朋友和设计师的老妈。你可以感觉得到在游戏的什么地方,设计师从那儿开始游戏的内容而不是游戏玩法:这些是有深度、包含剧情和内容层次的游戏,但没有人看得出,因为游戏玩法太无聊,玩家才玩了五分钟就不想玩了。如果你先考虑学生的经验,再开始制定课程计划,而不是根据你觉得有趣的方式(学生的想法可能跟你不太一样)来设计课堂或以目录(可能直到你上完课都没提到)为基础,那么你的课堂会是怎么样的呢?

结语

什么是游戏?决策是核心。如果严格地分析游戏(你自己的或别人的),请注意玩家在做什么决策、有多少有意义的决策以及为什么。你理解得越多,你就会越有经验。

游戏并非天生就擅长向玩家教授技能。(无论这些技能有用还是没用。)学习一项新技术——通过完成那些逼使你努力然后提高技能水平的挑战。技能水平是让玩家进入“心流”状态的先决条件之一。当大脑处于“心流”状态时,人的愉悦程度最高。游戏中感到“有趣”的情绪大多来自这种状态。

好啦,我们的谜题解答完毕!你现在知道了“乐趣”来自哪里,以及如何制造“乐趣”。但这还只是开头,日后我们还将继续探索“乐趣”的本质。

游戏邦注:原文发表于2009年7月20日,所涉事件及数据以当时为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Level 7: Decision-Making and Flow Theory

I’m excited about this week, because this is where we’re going to really get into the essence of game design, starting today with decision-making and continuing this Thursday with the nature of fun. These are some of my favorite topics to discuss, because it is the interactivity between players and systems that sets games apart from most other traditional media. This is where the magic of play happens, and as a systems designer, this strikes at the heart of what I deal with when making a game.

Decisions

As Costikyan pointed out in I Have No Words, we often use the buzzword “interactivity” when describing games when we actually mean “decision-making.” Decisions are, in essence, what players do in a game. Remove all decisions and you have a movie or some other linear activity, not a game. As pointed out in Challenges, there are two important exceptions, games which have no decisions at all: some children’s games and some gambling games. For gambling games, it makes sense that a lack of decisions is tolerable. The “fun” of the game comes from the thrill of possibly winning or losing large sums of money; remove that aspect and most gambling games that lack decisions suddenly lose their charm. At home when playing only for chips, you’re going to play games like Blackjack or Poker that have real decisions in them; you are probably not going to play Craps or a slot machine without money being involved.

You might wonder, what is it about children’s games that allow them to be completely devoid of decisions? We’ll get to that in a bit.

Other than those two exceptions, most games have some manner of decision-making, and it is here that a game can be made more or less interesting. Sid Meier has been quoted as saying that a good game is a series of interesting decisions (or something like that), and there is some truth there. But what makes a decision “interesting”? Battleship is a game that has plenty of decisions but is not particularly interesting for most adults; why not? What makes the decisions in Settlers of Catan more interesting than Monopoly? Most importantly, how can you design your own games to have decisions that are actually compelling?

Things Not To Do

Before describing good kinds of decisions, it is worth explaining some common kinds of uninteresting decisions commonly found in games. Note that the terminology here (obvious, meaningless, blind) is my own, and is not “official” game industry jargon. At least not yet.

? Meaningless decisions are perhaps the worst kind: there is a choice to be made, but it has no effect on gameplay. If you can play either of two cards but both cards are identical, that’s not really much of a choice.

? Obvious decisions at least have an effect on the game, but there is clearly one right answer, so it’s not really much of a choice. Most of the time, the number of dice to roll in the board game RISK falls into this category; if you are attacking with 3 or more armies, you have a “decision” of whether to roll 1, 2, or 3 dice… but your odds are better rolling all 3, so it’s not much of a decision except in very special cases. A more subtle example would be a game like Trivial Pursuit. Each turn you are given a trivia question, and if you know the correct answer it could be said that you have a decision: say the right answer, or not. Except that there’s never any reason to not say the right answer if you know it. The fun of the game comes from showing off your mastery of trivia, not from making any brilliant strategic maneuvers. This is also, I think, why quiz shows like Jeopardy! are more fun to watch than to play.

? Blind decisions have an effect on the game, and the answer is not obvious, but there is now an additional problem: the players do not have sufficient knowledge on which to make the decision, so it is essentially random. Playing Rock-Paper-Scissors against a truly random opponent falls into this category; your choice affects the outcome of the game, but you have no way of knowing what to choose.

These kinds of decisions are, by and large, not much fun. They are not particularly interesting. All three represent a waste of a player’s time. Meaningless decisions could be eliminated, obvious decisions could be automated, and blind decisions could be randomized without affecting the outcome of the game at all.

In this context, it is suddenly easy to see why so many games are not particularly compelling.

Consider the trivia game that popularized the genre, Trivial Pursuit. First you roll a die, and move in any direction, so which location you land on is a decision.

Only a few spaces on the board help you towards your victory condition, so if you can land on one of those it is an obvious decision. If you can’t, your choice generally amounts to which category you’re strongest at, which is again obvious (or blind, to the extent that you don’t know what question you would get in each category until after you choose). Once you finish moving, you’re asked a trivia question. If you don’t know the answer, there is no decision to be made. If you do know the answer, there is a decision of whether to say it or not… but there is no reason not to, so again it is an obvious decision.

Or consider the board game Battleship which seems to keep coming up in our discussions. Just about every decision made in this game is blind. You are given no information on which to base your decision of what space to fire at. Once you hit an enemy ship you do have some information, but you still don’t know which direction the ship is oriented (horizontally or vertically) or where its endpoints are, so the decision is more constrained but not any less blind.

Or consider Tic-Tac-Toe, which has interesting strategic decisions until you reach the age where you master it and realize the way to always win or draw, at which point the decisions become obvious.

What Makes Good Decisions?

Now that we know what makes weak decisions, the easiest answer is “don’t do that!” But we can take it a little further. Generally, interesting decisions involve some kind of tradeoff. That is, you are giving up one thing in exchange for another. These can take many different forms. Here are a few examples (again I use my own invented terminology here):

? Resource trades. You give one thing up in exchange for another, where both are valuable. Which is more valuable? This is a value judgment, and the player’s ability to correctly judge or anticipate value is what determines the game’s outcome.

? Risk versus reward. One choice is safe. The other choice has a potentially greater payoff, but also a higher risk of failure. Whether you choose safe or dangerous depends partly on how desperate a position you’re in, and partly on your analysis of just how safe or dangerous it is. The outcome is determined by your choice, plus a little luck… but over a sufficient number of choices, the luck can even out and the more skillful player will generally win. (Corollary: if you want more luck in your game, reduce the total number of decisions.)

? Choice of actions. You have several potential things you can do, but you can’t do them all. The player must choose the actions that they feel are the most important at the time.

? Short term versus long term. You can have something right now, or something better later on. The player must balance immediate needs against long-term goals.

? Social information. In games where bluffing, deal-making and backstabbing are allowed, players must choose between playing honestly or dishonestly. Dishonesty may let you come out better on the current deal, but may make other players less likely to deal with you in the future. In the right (or wrong) game, backstabbing your opponents may have very negative real-world consequences.

? Dilemmas. You must give up one of several things. Which one can you most afford to lose?

Notice the common thread here. All of these decisions involve the player judging the value of something, where values are shifting, not always certain, and not obvious.

The next time you play a game that you really like, think about what kinds of decisions you are making. If you have a particular game that you strongly dislike, think about the decisions being made there, too. You may find something about yourself, in terms of the kinds of decisions that you enjoy making.

What About Action Games?

At this point, the video gamers among you are wondering how any of this applies to the latest First-Person Shooter. After all, you’re not exactly strategizing about resource management tradeoffs in the middle of a heated battle where bullets and explosions are flying all around you.

The short answer here is that you are making interesting decisions in such games, and in fact you are making them at a much faster rate than normal – often several meaningful decisions per second. To compensate for the intense time pressure, the decisions tend to be much simpler: fire or dodge? Aim or move? Duck or jump?

Time limits can, in fact, be used to turn an obvious decision into a meaningful one. Another way I prefer to say this is that time pressure makes us stupid. For a more thorough discussion of action games and how skill relates to them, see Chapter 7 (Twitch Skill) in Challenges for Game Designers.

Emotional Decisions

There is one class of decisions that is useful to consider: decisions that have an emotional impact on the player. The decision of whether to save your buddy (while using some of your precious supplies) or leave him behind to die (potentially denying yourself some AI-assisted help later on) in Far Cry is a resource decision, but it is also meant to be an emotional one – and certainly, an identical decision made on a real-life battlefield would come down to more than just an analysis of available resources and probabilities. Likewise, the majority of players do not play through a game with moral choices (such as Knights of the Old Republic or Fable) as pure evil – not because “evil” is a suboptimal strategy, but because even in a fictional simulated world, a lot of people can’t stomach the thought of torturing and killing innocent bystanders.

Or consider a common decision made at the start of many board games: what color are you? Color is usually just a way to uniquely identify player tokens on the board, and has no effect on gameplay. However, many people have a favorite color that they always play, and can become quite emotionally attached to “their” color. It can be rather entertaining when two players who “always” play Green, play together for the first time and start arguing over who gets to be Green. If player color has no effect on gameplay, it is a meaningless decision. It should therefore be uninteresting, and yet some players paradoxically find it quite meaningful. The reason is that they are emotionally invested in the outcome. This is not to say that you can cover up a bad game by artificially adding emotions; but rather, as a designer, be aware of what decisions your players seem to respond to on an emotional level.

Flow theory

Let’s talk a little bit about this elusive concept of “fun.” Games, we are told, are supposed to be fun. The role of a game designer is, in most cases, to take a game and make it fun. I’ve used the word “fun” a lot in this course without really defining it, and it has understandably made some of you uncomfortable. Notice I usually enclose the word “fun” in quotation marks, on purpose. My reasoning is that “fun” is not a particularly useful word for game designers. We instinctively know what it means, sure, but the word tells us nothing about how to create fun. What is fun? Where does it come from? What makes games fun in the first place? We will continue to talk about this on Thursday, but I want to start talking about it now. I’m sure you can agree it has been long enough.

Interesting decisions seem like they might be fun. Is that all there is to it? Not entirely, because it doesn’t say anything about why these kinds of decisions are fun. Or why uninteresting decisions are still fun for children. For this, we turn to Raph Koster.

What a lot of Koster’s Theory of Fun boils down to is this: the fun of games comes from skill mastery. This is a pretty radical statement, because it equates “fun” with “learning”… and at least when I was growing up, we were all accustomed to regard “learning” with “school” which was about as not fun as you could get. So it deserves a little explanation.

Theory of Fun draws heavily on the work of psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (pronounced just like it’s spelled, in case you’re wondering), who studied what he called the mental state of “flow” (we sometimes call it being “in the flow” or “in the zone”). This is a state of extreme focus of attention, where you tune out everything except the task you’re concentrating on, you become highly productive, and your brain gives you a shot of neurochemicals that is pleasurable – being in a flow state is literally a natural high.

Csikszentmihalyi identified three requirements for a flow state to exist:

? You must be performing a challenging activity that requires skill.

? The activity must provide clear goals and feedback.

? The outcome is uncertain but can be influenced by your actions. (Csikszentmihalyi calls this the “paradox of control”: you are in control of your actions which gives you indirect control over the outcome, but you do not have direct control over the outcome.)

If you think about it, these requirements make sense. Why would your brain need to enter a flow state to begin with, blocking out all extraneous stimuli and hyper-focusing your attention on one activity? It would only do this if it needs to in order to succeed at the task. What conditions would there have to be for a flow state to make the difference between success and failure? See above – you’d need to be able to influence the activity through your skill towards a known goal.

Csikszentmihalyi also gave five effects of being in a flow state:

? A merging of action and awareness: spontaneous, automatic action/reaction. In other words, you go on autopilot, doing things without thinking about them. (In fact, your brain is moving faster than the speed of thought – think of a time when you played a game like Tetris and got into a flow state, and then at some point it occurred to you that you were doing really well, and then you wondered how you could keep up with the blocks falling so fast, and as soon as you started to think about it the blocks were moving too fast and you lost. Or maybe that’s just me.)

? Concentration on immediate tasks: complete focus, without any mind-wandering. You are not thinking about long-term tradeoffs or other tasks; your mind is in the here-and-now, because it has to be.

? Loss of awareness of self, loss of ego. When you are in a flow state, you become one with your surroundings (in a Zen way, I suppose).

? There is a distorted sense of time. Strangely, this can go both ways. In some cases, such as my Tetris example, time can seem to slow down and things seem to happen in slow motion. (Actually, what is happening is that your brain is acting so efficiently that it is working faster; everything else is still going at the same speed, but you are seeing things from your own point of reference.) Other times, time can seem to speed up; a common example is sitting down to play a game for “just five minutes”… and then six hours later, suddenly becoming aware that you burned away your whole evening.

? The experience of the activity is an end in itself; it is done for its own sake and not for an external reward. Again, this feeds into the whole “here-and-now” thing, as you are not in a mental state where you can think that far ahead.

I find it ironic, when a typical kid is in their “not now, I’m playing a game” mental state, the parent complains that they are “zoned out.” In fact, the gamer is in a flow state, and they are “zoned in” to the game.

Flow States in Games

Simplifying this a bit, we know that to be in a flow state, an activity must be challenging. If it is too easy, then the brain has no reason to waste extraneous mental cycles, as a positive outcome is already assured. If it is too difficult, the brain still has no reason to try hard, because it knows it’s just going to fail anyway.

The goal is to hit that sweet spot where the player can succeed… but only if they try hard. You’ll often see a graph that looks like this, to demonstrate:

All this says is that if you have a high skill level and are given an easy task, you’re bored; if you have a low skill level and are given a difficult task, you’re frustrated; but if the challenge level of an activity is comparable to your current skill level… flow state! And this is good for games, because this is where a lot of the fun of games comes from.

Note that “flow” and “fun” are not synonyms, although they are related. You can be in a flow state without playing a game (and in fact without having fun). For example, an office worker might get into a flow state while filling out a series of forms. They may be operating at the edge of their ability in filling out the forms as efficiently as possible, but there may not be any real learning going on, and the process may not be fun, merely meditative. (Thanks to Raph for clarifying this for me.)

One Slight Problem

When you are faced with a challenging task, you get better at it. It’s fun because you are learning, remember? So, most people start out with an activity (like a game) with a low skill level, and if the game provides easy tasks, then so far so good. But what happens when the player gains some competency? If they keep getting the same easy tasks, the game becomes boring. This is essentially what happens in Tic-Tac-Toe when a child makes the transition to understanding the strategy of the game.

By the way, we can now answer our earlier question: why can children’s games get away with a lack of meaningful decision-making? The answer is that young children are still learning valuable skills from these games: how to roll a die, move a token on a board, spin a spinner, take turns, read and follow rules, determine when the game ends and who wins, and so on. These skills are not instinctive and must be taught and learned through repeated play. When the child masters these skills, that is about the time when decision-less games stop holding any lasting appeal.

Ideally, as a game designer, you would like your game to have slightly more lasting playability than Tic-Tac-Toe. What can you do? Games offer a number of solutions.

Among them:

? Increasing difficulty as the game progresses (we sometimes call this the “pacing” of a game). As the player gets better, they get access to more difficult levels or areas in a game. This is common with level-based video games.

? Difficulty levels or handicaps, where better players can choose to face more difficult challenges.

? Dynamic difficulty adjustment (“DDA”), a special kind of negative feedback loop where the game adjusts its difficulty during play based on the performance of

the player.

? Human opponents as opposition. Sure, you can get better at the game… but if your opponent is also getting better, the game can still remain challenging if it has sufficient depth. (This can fail if the skill levels of different players fall out of synch with one another. I like to play games with my wife, and we usually both start out at about the same skill level with any new game that really fascinates us both… but then sometimes, one of us will play the game a lot and become so much better than the other, that the game is effectively ruined for us. It is no longer a challenge.)

? Player-created expert challenges, such as new levels made by players using level-creation tools.

? Multiple layers of understanding (the whole “minute to learn, lifetime to master” thing that so many strategy games strive for). You can learn Chess in minutes, as there are only six different pieces… but then once you master that, you start to learn about which pieces are the most powerful and useful in different situations, and then you start to see the relationship between pieces, time, and area control, and then you can study book openings and famous games, and so on down the rabbit hole.

? Jenova Chen’s flOw provides a novel solution to this: allow the player to change the difficulty level while playing based on their actions. Are you bored?

Dive down a few levels and the action will pick up pretty fast. Are you overwhelmed? Run back to the earlier, easier levels (or the game will kick you back on its own if needed).

You’ll notice that when we read in a review that a game has “replayability” or “many hours of gameplay” what we are often really saying is that the game is particularly good at keeping us in the flow state by adjusting its difficulty level to continue to challenge us as we get better.

Why Games?

You might wonder, if flow states are so pleasurable and they are where this elusive and mysterious “fun” comes from, why do we design games to do this and not some other medium? Why not design productive tasks to induce flow states, for example, so that maybe we could get a few million people working on discovering a cure for cancer instead of playing World of Warcraft? Why not design college classes to induce flow states, so that a student could learn a typical 50-hour class in a week (the same way they might play through a 50-hour RPG on their PlayStation) instead of having that same class take an entire 10 or 15 weeks?

Games just happen to be naturally good at putting players in a flow state, so it is much easier to design a fun game than a fun course in Calculus. As Koster points out in A Theory of Fun, the brain is a great pattern-matching machine, and it is the finding and understanding of patterns that is what is happening when our brain is in a flow state. I think games bring this out really well because you have three levels of patterns: feeling the Aesthetics, discerning the Dynamics, and finally mastering the Mechanics (in the MDA sense). Since every game has these three layers of patterns, games are three times as interesting as most other activities.

“Edutainment” Games

You might think that, if games are so great at teaching and if learning is so darned pleasurable, that educational games would be more fun than anything. In reality, of course, “Edutainment” is a dirty word that we only mention when forced, as the vast majority of games that bill themselves as “fun… and educational!” are actually neither. What’s going on here?

Many “Edutainment” games work like this: first you’ve got this game, and you play it, and it’s maybe kind of fun. And then the game stops, and tries to give you some kind of gross, icky, disgusting learning. And as a reward for doing the learning, you get to play the game again. Gameplay is framed as a reward for the inherently unpleasurable task of learning something. We have a name for this: chocolate-covered broccoli.

I think this design contains an error of thinking, and this infects the design of such games at a fundamental level, invalidating the whole premise. The error is the separation of “learning” and “fun” because, as you now know, these are not separate concepts but rather identical (or at least strongly related). The assumption that learning is not fun and that fun cannot be inherently educational undermines the entire game… and incidentally, also reinforces the extremely damaging notion that education is a chore and not a pleasure.

It would be wonderful if we could stop teaching that “learning is not fun” lesson to our children. It would certainly make my life a lot easier as a teacher, if I did not have to first convince my students that they should be intrinsically motivated to do well in my classes.

What if you want to design a game that has the primary purpose of teaching, then? That is a subject that deserves a course of its own. My short answer: start by isolating the inherently fun aspects of learning the skills you want to teach, and then use those as your core mechanics. By integrating the learning and the gameplay (rather than keeping them as separate concepts or activities), you take a large step towards something truly worthy of the “fun, and educational” label.

A Note for Teachers

If you’ve accepted everything in this lesson so far, you might see a parallel with teaching. If learning is inherently fun, think about what you can do to draw that out of your subject.

? How many interesting decisions do your students make? I once saw a statistic that the average college student raises their hand in class once every ten weeks

– that’s three meaningful decisions per year! Can you do better? Consider giving a choice of assignments (with built-in tradeoffs: for example, an easy-but-boring homework or a difficult-but-interesting one). Ask lots of questions in class that get students involved. Have class discussions or debates.

? Are too many of your students bored or overwhelmed, because your class is at a difficulty that is too low or too high? Games have this problem too, and often solve it through including multiple difficulty levels; consider having a tiered grading system where remedial students should be able to pass if they can at least put in the work to grasp the basics, while offering advanced students extra work that is more interesting. Offer the course content in layers, first going over the very basics in a “For Dummies” way that everyone can get, then add the main details that are really important, and finally give some advanced applications that only some students might understand, but that are interesting enough that students will at least have some incentive to reach a bit.

? The most fun games are designed in a player-centric manner, concentrating first on providing a quality experience. You can tell a game where the designer made a game that they wanted to play, because it sold a total of five copies to the designer, the designer’s close friends, and the designer’s mom. You can also tell a game where the designer started with content rather than gameplay; these are the games that have deep, involving stories and incredible layers of content, but no one sees them because the gameplay is boring and people stop playing after five minutes. What would your class be like if you start your lesson plans by thinking of the student experience, rather than designing a class that you find interesting (your students might not share your research interests), or designing a class based around content (which is probably not engaging until you bring it to life)?

Lessons Learned

Decisions are the core of what a game is. When critically analyzing a game (yours or someone else’s), pay attention to what decisions the players are making, how meaningful those decisions are, and why. The more you understand about what makes some decisions more compelling than others, the better a game designer you are likely to be.

Games are unnaturally good at teaching new skills to players. (Whether those skills are useful or not, varies from game to game.) Learning a new skill – by being given a challenge that forces you to try hard and increase your skill level – is one of the prerequisites for putting players in a flow state. Flow states are an intensely pleasurable state for the brain to be in, and a lot of the feeling of “fun” that comes from playing games comes from being in the flow.

There it is! Mystery solved! You now know everything there is to know about where “fun” comes from and how to create it. Okay, not really. But this is a start, and we will probe a bit deeper into the nature of “fun” this Thursday.(source:gamedesignconcepts)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号