如何才能创造出堪称“高端艺术”的游戏?

作者:Jason Rohrer

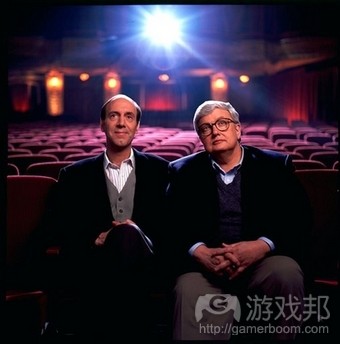

举世闻名的电影评论人,兼让人后怕的电子游戏批评者Roger Ebert在2007年7月份说道:

“任何东西都可以成为艺术。甚至是Campbell(游戏邦注:美国最大的浓缩汤汁罐头公司)的汤汁罐头也行。”

然而,Ebert却继续补充道,电子游戏却从来都不算是一种“艺术”。

Ebert一直坚守“游戏不是艺术”这个观点2年半之久,并承受着来自于游戏粉丝们激昂的回应。游戏社区一直就这个问题进行内部抗衡——我们还未与Ebert进行争辩,而这么长时间我们都是在游戏领域中进行彼此间的争论。

许多反对Ebert意见的人士都拿Ebert提出的论据为游戏做辩解,即既然任何东西都可以成为艺术,那么游戏自然也是了。以此欲终结讨论。

当然了,这些游戏支持者也并未直截了当地陈述了自己的观点;相反地,他们以文化产品的生存并不存在任何功利价值为陈述点。如果人类创造了一件产品,但是却不能靠它吃饭,只能用以取暖或者依靠,那么它就是一种艺术品。甚至有人利用这一论据将体育运动也拉拢到艺术行列中。

这个所谓的“功利测试”是一个很棒的思维实验,但是它最终却结束了关于游戏的测试。我们需要诚实地面对自己:真正摸着自己的良心,撇开所有的愤慨,我们其实都理解Ebert的观点,是吧?而且不只一点点?

让我们正视:通常来看,游戏其实糟糕透顶!大多数游戏只是在重复播放一些肤浅的内容。玩这些游戏只是让我们不断地在浪费宝贵的时间,而且除了休闲娱乐,我们也感受不到其它有意义的内容了。事实上,真的很难找到一款真正优秀的游戏能够得到Roger Ebert的认可而成为他口中的艺术品,甚至可能每一代掌机问世,才有一款这样的游戏。所以我们更加难以将游戏定义为所谓的“全艺术”媒介。确实,即使是通过实用测试的游戏也不足以与康定斯基(游戏邦注:出生于俄罗斯的画家和美术理论家)的画作相匹敌。

Ebert的观点是对的,至少现在是这样。所以比起正面否决他的观点,我们应该列举出一些明确的目标证明他是错误的。也就是我们应该为他呈现一款真正具有艺术性的游戏,而让他心服口服地改变观点。这就是我们作为游戏设计者在今后数十年的首要任务。

但是如果我们继续执拗于“任何东西都是艺术”或者横冲直撞地去证实这个定义,我们可能永远都不会开始创造具有艺术性的游戏。因为我们只需要说服Ebert,并希望他能将游戏定义为“高端艺术”。虽然他未明确给予我们所想要的论据,但是从他的观点中我们也找到了一些有帮助的内容,如艺术能够帮助我们“变成更有文化,更有教养且更有感情的人;以及艺术还能够让我们成为更加“复杂,有思想,有见解,机智,聪明且冷静之人等等”。

也许这些崇高的细目清单并不能直击所有人的心灵,但是对于我们来说这却是个起跑点。现在有多少游戏还缺少这些目标?很少。我们制作游戏的目标很明确,而这个领域也极为宽广,所以我们有信心能够创造出这种艺术性游戏。

现在,我们需要思考一个核心问题,即我们要如何做才能让游戏触及这些崇高目标?以及如何才能在游戏中贯穿艺术表达?

既然我们都向Ebert这位影评人发起了挑战,那么不妨以他的本行——电影作为我们的出发点。电影自然是一种艺术形式,而关于这个争论早在60年前就已经得出了结论。在当代一些争论中,人们总是拿游戏与电影做比较,特别是在关于“游戏是艺术”的争论中。Ebert因为否定了这种比较而在游戏领域获得了很多负面的声誉,但是也有许多正面观点认为游戏正在逐步接近电影。我们应该怀抱希望,期待着游戏终有一天能够超越电影,并成为一种不可取代的现代文化媒介。

但是如果我们追求艺术表达的过程是将更多电影元素添加到游戏中,并逐渐超越游戏元素,那也就等于我们是在强调电影比游戏更加具有艺术性。所以,我们应该好好地对比游戏与电影,并找出两者间的基本差异,然后尽所能地将游戏区别于电影进行发展。我们必须停止对于电影的模仿,并开始挖掘游戏这种媒介的特殊表达潜力。

电影制作人拥有多种多样的工具,特别是很多先于它出现的媒介表达方式。电影制作人可以通过摄影机角度,摄影机移动,片段剪辑,灯光,颜色,音效,音乐,脚本语言,表演,布景设计,服装设计,动画等方法去传达自己的想法。最优秀的电影,特别是“高端艺术”电影可以尽可能地使用多种工具去传达定影制作人希望表达的内容。

而游戏开发者的工具箱中也包含有电影制作人的所有工具,忽略那些技术局限,游戏也算是一种电影的延伸了。换句话说,游戏可以实现电影的任何做法,但是游戏也具有一个额外功能,能够让它区别于其它媒介,也就是游戏玩法。

我所说的游戏玩法是指特定游戏中的游戏机制集合体,而游戏机制则是指那些能够支配多种游戏部件交互作用的规则。虽然这个定义没多大说服力,但是比起将游戏玩法称之为“玩家在游戏中的所有行动”,前一种说法确实好多了。

现在,请你振作精神,因为我将重申一个古老的游戏设计智慧,即游戏玩法是游戏最重要的组成部分。

确实,这个咒语在我们的脑子里吟诵了多年。不管是设计者,评论家还是玩家都认可这一说法。然而我们对于游戏玩法的重视还出于一个较为平淡的原因,即这是游戏中很“有趣”的一部分,这个部分能够吸引玩家的注意。而还有一个更有趣的原因:因为正是游戏玩法的存在才使得游戏显得独特并区别于其它媒介。如果你不是受到游戏玩法的吸引而玩游戏,那么你还不如去看电影或者读书。

不幸的是,游戏玩法很难与游戏所要表达的内容达成共鸣。并不是因为游戏玩法是设计之后添加的想法,相反地,游戏玩法是一种深谋远虑,甚至是开发者的艺术观点等多种元素都是基于游戏玩法而形成的。不同游戏类型(游戏邦注:包括第一人称射击游戏,秘密行动类游戏,平台游戏,角色扮演游戏,即时战略游戏,探险游戏等)拥有不同的游戏机制。而也是这种游戏机制将游戏与电影区别开来,因为电影是基于影片内容以及索要表达的情感而进行分类。

很多现代主流游戏所传达的美学体验都符合Ebert对于艺术的要求,但是因为这些体验都是后来才加入游戏玩法中,所以它们只能算是硬塞进游戏场景或故事主线轴中的内容。而如此的结果便是游戏玩法,即游戏的核心内容很难与游戏整体的艺术表达趋于同步。

《生化奇兵》便是这种不协调性的典型例子。游戏中的非游戏玩法元素(如布景设计,录音日记以及线性故事)让游戏能够因此找到极端的Randian哲学所存在的不足之处。换句话说,这款游戏的游戏玩法包含了第一人称射击游戏中的升级要素。

如果我们正在制作一款以个人自由对抗社会公德为主题的游戏,就像《生化奇兵》一样,何不让游戏机制直接对这些议题进行探索?为何不直接在游戏玩法中阐明艺术家的观点而设置在故事以及环境设计中?从《生化奇兵》的开发历史来看,因为在游戏设计者想到要如何表达之前他们已经将游戏设定为第一人称射击游戏了。因此,《生化奇兵》已经成为了误导“游戏玩法优先”设计哲学的另一大牺牲者。

所以为了制作一款称得上是艺术品的游戏,我们应该采取另外一种方法。我们必须知道,我们想通过游戏表达些什么,然后再有针对性地设置游戏机制。也就是说我们的游戏核心,即游戏玩法必须承载着我们所要表达的所有内容。

如果我们想要通过游戏玩法去传达更多内容,就必须尽可能地摆脱其它媒体的帮助,如过场动画等等。当将来的某一天我们回首现在的时代,可能会对现在的游戏设计仍在使用过场动画和线性叙述而忍俊不禁,就像我们现在会窃笑过去依赖于字幕卡片传达游戏故事的旧电影一样。

我们现在的游戏玩法距离Ebert所说的有价值的艺术形式还有多远的差距?已经有一些游戏设计者开始朝这个方向而努力了。

Rod Humble通过在《The Marriage》中使用游戏机制而更好地传达了游戏中脆弱且无常的关系以及《Stars over Half Moon Bay》中的复杂创造过程。Jonathan Blow在《幻境》中使用了时间控制机制去表达游戏中的犯错,亏损,追求,领悟以及放弃等行为。Danny Ledonne在《Super Columbine Massacre RPG!》中将标准的角色扮演游戏机制进行了适当的调整,从而让游戏的转折点具有更加复杂的深意。暂且不提我的设计努力,我想说这四款游戏是我所知道的直接通过游戏玩法而提供给我们富有文化,文明,情感,复杂,有想法,有洞察力,机智,聪明且充满哲学的内容。

让我们再次回到对于Ebert的挑战话题中。在我所列出的游戏清单中是否有哪一款游戏能够得到他的认可?很遗憾的是,都没有。我所列举的游戏虽然都进行了不一样的尝试,但是结果却未能够取得不错的成绩。我们仍在学习如何更好地通过游戏设置去传达游戏,因为现在的我们还未能做好这一点。

我作为一名游戏设计者以及有经验的游戏玩家,虽然说《时空幻境》这款游戏算得上是我们文化中一部非常杰出的游戏作品,但是我却仍然没有勇气拿着它向Ebert征求意见。有可能Ebert只能笨手笨脚地操纵控制器,笨手笨脚地处理简单的智力问题,并在自己花费了7个多小时的摸索时间但却仍然困惑于这款游戏深层次的游戏玩法后而最终放弃。

在这里,我认为这是一种“不正当的违规行为”。因为对于一个毫不精通游戏的Ebert来说,他连游戏的基本关卡都处理不了了,还怎么对游戏做出评判?但是,Ebert面对游戏所遇到的这些障碍正是帮助我们应对他的挑战的一些重要因素。我们需要想出,是哪些“基本”因素让他感到困惑?是复杂的控制器?还是古怪的智力问题?或者是他认为游戏耗费了太多时间?而在整个游戏过程中哪一类媒介阻碍了他的游戏乐趣?

的确,我们拥有一些非常有领悟的高手并制作了一些能够称得上是高端艺术的游戏作品,但是这还远远不够。为了让所有人都认可游戏是一种高端艺术,我们需要想办法让所有人在整个游戏过程中都能够“顺利”地玩游戏。

只有当我们制作出这些游戏,我才敢毫无畏惧地反驳Ebert的观点,并吸引他也加入游戏中。我想只有听到Ebert发自内心的感叹“哇”,我们才算真正的赢家。

游戏邦注:原文发表于2008年6月24日,所涉事件和数据均以当时为准。

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The Game Design of Art

by Jason Rohrer

“Anything can be art. Even a can of Campbell’s soup.”

So admitted Roger Ebert, world-famous movie reviewer and notorious videogame detractor, back in July of 2007. However, continued Ebert, videogames will never be “high art.”

Ebert has held fast to his “games cannot be art” position for two and a half years, braving an e-firestorm of responses from passionate game fans. The gaming community has folded this fight into itself – we haven’t just argued with Ebert, we’ve also debated endlessly with each other.

Many of Ebert’s opponents have unwittingly invoked a fragment of Ebert’s argument in defense of games: Anything can be art, therefore games are art. End of discussion.

Of course, these game proponents don’t state their position so baldly; instead, they point to cultural products that have no utilitarian value for survival. If humans make it, but you can’t eat it, keep warm with it or sit on it, then it’s art. I’ve even heard this argument expanded to lasso sports into the art corral.

This “utilitarian test” is a nice thought experiment, but it ends up derailing the debate about games. We need to be honest with ourselves: deep down inside, buried beneath our indignations, we all understand where Ebert is coming from, right? Not even a little bit?

Let’s face it: Games, in general, suck. Most are repetitive and shallow. Most eat up precious moments of our lives without giving us anything more than idle entertainment in return. The really good games, the ones that we would only be half-embarrassed to show Roger Ebert as art samples, are few and far between – maybe one game per console generation, if that. This is hardly what we would recognize as an “art-full” medium. Yes, games pass the zero-utility test, but that’s not enough to stand them up proudly next to a Kandinsky painting.

Ebert is right, at least so far. Instead of dismissing his position, however, we should tackle it head-on with the explicit goal of proving him wrong. We must present him with a game so artful that it makes him eat his hat. That is our main task as game designers over the next decade – I hereby decree it

But if we cling to the notion that “anything is art” or throw our hands in the air when attempting a definition, how can we ever begin our quest to make this game? Since we only need to convince Ebert, we’ll let him provide a definition of “high art.” He may not have been as explicit or concise as we might like, but he left us a few crumbs to nibble on. For example, art might help us “make ourselves more cultured, civilized and empathetic.” Additionally, art might cause us to become more “complex, thoughtful, insightful, witty, empathetic, intelligent, philosophical (and so on).”

Those lofty laundry lists won’t feel like direct hits for everyone, but they make a fine starting point. How many existing games do something even remotely like this? Not many. Our goal is clear, the field is wide open and we can get to work.

Now we’re ready for the central question: How can we make a game that hits some of those lofty targets? How do we deliver artistic expression through our games?

Since we’ve already taken this battle to Ebert’s doorstep, we can use film as our starting point. Film is certainly capable of high art, and the “films cannot be art argument” is 60-years dead. Games have been frequently compared with films in contemporary discussions, especially in the “games as art” debate. Ebert is infamous for his negative comparisons, but even the positive comparisons have seen games as asymptotically approaching films. Someday, we’re supposed to hope, games will become indistinguishable from – and perhaps even replace – films as the chosen expressive medium of modern culture.

But if we pursue artistic expression by making our games more film-like and less game-like, we simply reinforce the notion that films are more art-capable than games. Instead, we should compare games and films to identify their fundamental differences, then steer games away from films as hard as we can. We need to stop aping films and start tapping into the unique expressive powers of our medium.

The film toolbox is pretty full, essentially making it a superset of almost all the mediums that came before it. A filmmaker can use camera angles, camera motion, cuts, lighting, color, sound, music, scripting, acting, set design, costume design, animation and so on to communicate his vision. The very best films, particularly “high art” films, employ all their chosen tools in a way that resonates with what they are trying to express.

A game developer’s toolbox contains a complete set of the filmmaker’s tools; ignoring technical limitations, the medium can be seen as a superset of film. In other words, a game can do anything that a film can do. But games have one additional feature that sets them apart from any other medium: gameplay.

I shouldn’t use a vague term like “gameplay” without reigning it in a bit. By gameplay, I mean the collection of game mechanics in a given game, and by game mechanics, I mean the rules that govern the interaction of the various game components. That’s a pretty dry definition, but I find it to be more useful than a looser one like “‘gameplay’ is whatever the player does.”

Now brace yourself as I restate an ancient piece of game design wisdom and pretend that it’s novel: Gameplay is the most important part of a game.

Yes, we’ve been reciting this mantra for decades. Designers, reviewers and players all believe it. However, we generally worship gameplay for a rather uninspiring reason: It’s the “fun” part of the game, the part that hooks you. Here’s a more interesting reason that gameplay is important: because it sets games apart from other mediums and makes them unique. If you’re not there for the gameplay, why are you playing a game instead of watching a film or reading a book?

Unfortunately, gameplay rarely resonates with what a game is actually trying to express. It’s not that gameplay is an afterthought in the design process. In fact, the exact opposite is usually true: Gameplay is the forethought, and everything else, including the developers’ artistic vision, is slapped on top of it. Consider the standard list of game genres (FPS, stealth, platformer, RPG, RTS, adventure), and notice how it’s really a list of game mechanics. This differs substantially from the way film is categorized, where genres are based on content and intended emotional effect.

Many modern, mainstream games deliver aesthetic experiences that might pass muster for Ebert, but because they’re an afterthought to the gameplay, they’re shoehorned in through cut scenes and linear storylines. The result is that the gameplay, the very heart of the game, is out of sync with the game’s overall artistic expression.

BioShock presents a perfect example of this kind of dissonance. Through its non-gameplay elements (set design, audio diaries and linear story), the game successfully explores the shortcomings of an extreme Randian philosophy. The gameplay, on the other hand, involves upgrade-heavy first-person shooting.

If we’re making a game that deals with individual freedom versus the good of society, as BioShock does, why not devise game mechanics that explore these issues directly? Why permit the artist’s vision to manifest itself in the storyline and environment design but not in the gameplay? The answer, looking at BioShock’s development history, is that the designers set out to make an FPS long before they figured out what they wanted to say with it. Thus, BioShock became yet another victim of the misguided “gameplay first” design philosophy.

To make games that are works of art, we should be taking the exact opposite approach. We should figure out what we want to express with our games and then devise game mechanics that best communicates that message. The heart of our games, the gameplay, should be our primary vehicle for expression.

Once we use gameplay to communicate more, we’ll rely on tools borrowed from other media, such as cut scenes, less and less. We may someday look back on this era and chuckle – the old days of game design, back when we were still using cut scenes and linear storylines – just as we chuckle now over old movies that relied on title cards to communicate something as simple as “Later that afternoon …”

How far away are we from expressing a meaningful, Ebert-worthy artistic vision directly through gameplay? There are a handful of game designers – and I mean a literal handful – that have started to do this already. The list is so short that I will present it here in its entirety.

Rod Humble used game mechanics to express the fragility and impermanence of relationships in The Marriage and the complexity of the creative process in Stars over Half Moon Bay. Jonathan Blow has used time-manipulation mechanics as a metaphor about mistakes, loss, pursuit, realization and resignation in Braid. Danny Ledonne has tweaked standard RPG mechanics to load his game’s turning point with complex meaning in Super Columbine Massacre RPG!.To say nothing of my own design efforts, these four games are the only works I know of that use their gameplay directly to make us more cultured, civilized, empathetic, complex, thoughtful, insightful, witty, intelligent, philosophical … and so on.

That brings us back to the Ebert challenge. Will any of the games on my list make him eat his hat? Sadly, no. My list calls out valiant attempts, not necessarily resounding successes. We’re still learning how to express through gameplay, and we’re not quite there yet.

For me, as a game designer and an experienced player, Braid stands among our culture’s highest artistic achievements, but I still couldn’t show it to Ebert without wincing. He would probably fumble with the controls, stumble through the simplest puzzles and abandon the game in frustration long before he put in the seven or more hours necessary to unveil the Braid’s deeper artistic payload.

Here, it’s tempting to call “foul.” As a non-gamer with no game literacy, Ebert would trip over the basics – so how could he possibly judge a game’s artistic merit? However, Ebert’s gaming handicap is one of the factors that makes this challenge worthwhile. After all, what are “the basics” that might hinder him? Difficult controls? Mind-bending puzzles? A time investment measured in hours rather than minutes? What other medium places such high hurdles in the way of simple start-to-finish consumption?

Yes, we’ve already produced games that strike the high-art chord with game-savvy folks, but that’s not enough. In order to make games that everyone might appreciate as high art, we first need to figure out how to make games that are playable – start-to-finish – by everyone.

Only with such a game in hand would I approach Ebert without fear of embarrassment and watch over his shoulder as he played. I would listen quietly for that single word issued almost inaudibly under his breath: “Wow.” And then I would know that we won.(source:escapistmagazine)

上一篇:阐述公平游戏的5大基本原则

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号