分析游戏设计标准之长期动机

作者:Brice Morrison

是什么支撑着玩家对一款游戏不离不弃?是什么让30秒的游戏经历拉长至30小时?

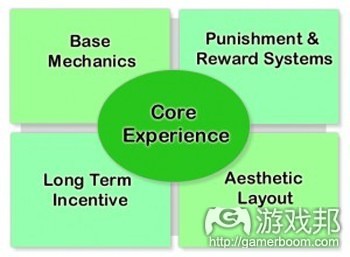

回答以上问题以前,我们先思考:玩家一开始玩游戏的动机是什么?显然,为了娱乐和享受。感受追击、挑战和寻找的紧张感,与他人的交流互动,提高自己的操作技能或在在游戏世界里探索冒险——这些都是核心体验,这也正是玩家最初开始玩游戏的原因。玩家希望得到有趣的体验,而游戏正好充当了玩家与体验之间媒介。

玩家开始游戏了,然后呢?每一款游戏都是一个新国度,玩家就是新国度的探索者,他们进入游戏寻找核心体验。在一路的跳跳跑跑中,玩家的游戏人生开始了。在游戏所创造的社会结构里,玩家与游戏互动。寻找体验的过程首先从了解并适应游戏的基本机制开始,也就是,学会在游戏世界里活动和生存。

玩家学会游戏的基本机制后,就可以学习更加宽泛的游戏玩法了。一开始玩家只会跳,但现在他知道跳以前得先看好位置;一开始玩家开门见山就谈敏感话题,现在他知道讨论时还要尊重对方;一开始玩家只知道见了敌人就开打,现在他知道对付红色的敌人得用红色的炮弹才有效。总之,他开始把自己的行为和游戏给予的结果联系起来,这样,他渐渐地明白了游戏世界还存在一个指导着”新国度的居民们”有所为有所不为的奖惩系统。这套高高地建立在基本机制之上的系统,指引着新国度的探索者们深入到核心体验之中。

再然后呢?

玩家们已经周游了这个国度(游戏本身)、理解了这个国度的体制、体验了这个国度的生活,还有什么值得他们留恋的呢?还有什么能让玩家不断地采取相同的举动、实施相同的策略、参与相同的活动,周而复始,不厌其烦,甚至仍然乐在其中?

为了目标而努力

在设计良好的游戏里,玩家坚持玩某款游戏是因为玩家有所追求,他们是为了某个目标而坚持不懈。所谓的目标未必如你所想的那样明确,甚至对玩家来说也不是非常重要。事实上,玩家可能没有意识到有一个目标在牵着他们的鼻子走。但确实有一个目标存在,即动机,让玩家坚持玩某款游戏。

在《超级马里奥兄弟》里,玩家只要不断地玩下去,就可以不断地通关不断地进入新地图。在典型的投币游戏,如《吃豆人》,玩家的长期动机就是拿到最高的积分。在《孢子》或《尼特》这类探索游戏里,玩家的目标只是不断地发现新东西、探索未知。以上这些都是在玩家已经“吃透”游戏后还能坚持玩下去的诱因所在。与游戏的其他成分一样,长期动机也可以扩宽游戏玩法。

没有长期动机的游戏算不上一款完整的游戏。以上体验类型更像是玩具。玩家先了解他们能做的行为(基本机制),再研究行为与结果之间的关系(奖惩系统),接着欣赏游戏的内容(美学布局),然后……没了——能研究的都研究了,能玩的都玩了。

玩具Vs.游戏

我们来看一个简单的例子:假如你走在大街上,看到一个蓝色的小皮球。“有意思!”你这么想着,“按一下会怎么样呢?”你按了一下皮球,它马上像被施了魔法一样蹦起来。“哇!有趣!”你这么想着又按了一下,不过这回好像没有跳得那么远了。“看来要让球一直跳,我得有节奏地按。”你验证了自己的猜想,假设成功。但是玩了不一会了你就厌倦了,不玩了。

这就是长期动机缺失的例子。但是,把这个按球活动中增中一个动机,就可以创造一个游戏了。想像一下,你看到球后,又在街的另一边看到一个盒子。“我要把这个球投到那个盒子里!”此时,你就有了一个动机——把球投进盒子里,你就赢了。

虽然这个例子很简短,但请注意是什么拓展了蓝球的玩法。当你把球投进对面的盒子里时,没有新的机制产生,也没有新的奖惩系统起作用。只是有一个目标激励着你去展开行动、指引着你去解决困惑。

普遍的长期动机

游戏中存在着许多长期动机,以下列举了一些比较普遍的类型:

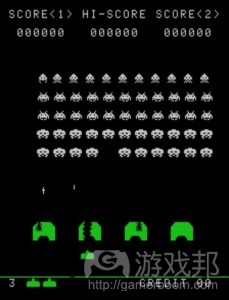

1、通关。这种类型的长期动机流行于早期的电脑游戏,且仍然在当下许多主流硬核游戏中长盛不衰。例如,战士必须穿过枪林弹雨,或者英勇的怪物猎人必须拯救王国,才能开启游戏的下一章节。玩家完成一个阶段就进入下一个阶段,整个游戏如此生生不息。通关的另一个变种是积分:玩家已经累积了115876点积分,只要再多射死一个太空入侵者就可以多拿一点积分,怎么能在这个关头就不玩了呢?

这种长期动机的升级版是给予玩家代表不同等级的奖牌金银铜,或代表不同积分层次的ABC,其本质就是“通关+积分”——玩家不仅要通过某道关卡,还要在这道关卡中争取得到最高分。这个版本非常接近我们将要提到的下一个流行的长期动机……

2、收集物品。有些玩家几近偏执,他们非得把每一块石头都翻开,每一个宝箱都打开才肯罢手。只要还有东西可以收集、还有事情可以做、还有任务可以完成,他们就绝不会离开,直到一切都处理得妥妥贴贴为止。这动机的变种包括角色满级、找到所有特殊物品或收集所有成就。

有些游戏对收集目标设置得很清楚,比如对每个成就都贴上标签。RPG给玩家开辟了许多副本,供玩家收集更高级的装备等。虽然副本并不需要玩家完成游戏(游戏邦注:除非是对成就解锁的拙劣模仿),但确实大大延长了玩家的游戏寿命。

3、获取新信息。许多游戏设置了悬念信息来吸引玩家继续玩下去。剧情就是其中一种。即使策略/战略游戏的关卡变得相当无聊,玩家仍然会继续玩下去,只要他们还关心Leon王子或自己喜欢的其他角色又发生了什么事。在《Flow》中玩家可以看到一个洞穴的深处或海洋底部,但尚不清楚会发生什么事。当那些形态各异的海怪若隐若现,玩家禁不住好奇潜入更深的水域,一窥究竟。

4、升级技能。《街霸》、《光晕》等动作游戏长久地占据玩家的“芳心”归功于升级技能。技能升级意味着攻克困境,或战胜强敌。为什么玩家能够一次又一次地沉浸于相同的战斗、相同的关卡、相同的武器和动作?这就是长期动机在起作用。长级技能有时候与等级系统相结合。如《光晕》,根据玩家的技能等级,安排遇上有相似技能的敌人。这就更进一步刺激玩家磨炼技术以战胜敌人。

单一或多重?明示或隐藏?

长期动机不一定要按时间来分。任何有意义的方式,只要能鼓励玩家继续游戏的都是长期动机。要在游戏中放入什么样的长期动机取决于游戏开发者。有些游戏看似不完整,正是因为缺乏真正的长期动机;有些游戏只有单一的长期动机;现代游戏大多有数个长期动机,可以说在深度上已经升级到专业水准。一款游戏有许多让玩家追随的东西,如果其中一种玩腻了,玩家还能继续追求另一种。如此一来,开发者就好像为游戏上了双重保险,有效地防止玩家从游戏中流失。

除了决定单一或多重动机,开发者还可以设计动机的明确程度。有些游戏赤裸裸地把长期动机摆出来,如列出各个阶段的成就或者给予玩家非常正式的得分,有些游戏则隐晦得多,玩家玩这两类游戏时的感受是非常不同的。像《Spore》或 《Flow 》这类目标(游戏邦注:通关+获取信息)相似的游戏,却很少向玩家透露长期动机,而是让玩家自己去寻找目标,从而产生一种他们是沿着自己的道路玩游戏的感觉。隐藏长期动机的好处是,让游戏本身看起来更接近核心体验;风险是,不明所以的玩家或者希望目标稍微明确的玩家可能会感到厌倦。

拓展游戏玩法:多给胡萝卜还是多给大棒?

如何拓展玩法、延长时间?最简单的方法就是给玩家长期动机。然而,开发者得注意了:完全依懒动机来拓展玩法可能会给游戏带来灾难性的后果。因此,开发者应该意识到长期动机对玩家的重要影响。

在此我给出一个直观的类比:胡萝卜和大棒。马想吃胡萝卜——奖励/长期动机。但胡萝卜悬挂在大棒上,想吃就得越过大棒的长度——任务或基本机制玩法。完成任务方得奖励。创造一种和谐的游戏玩法是一门保持胡萝卜和大棒效力的技术。

如果基本机制和奖惩系统就是游戏的固定焦点所在,那么要让玩家保持对游戏的热情,难度不大。强制玩家去思考、专注技能和长期游戏是设计师的目标。难点在于如何长久地保持游戏的新鲜度。如果你的游戏是以飞行为主题,那么我们可以很容易地想象到,玩家开着飞机从美国飞到加拿大。第一次学习飞行那是相当的有趣,第一次完成飞行任务那是相当的有成就感。

但是,这种体验不会长久。如果游戏需要飞得更远,如从加拿大飞到中国,那会怎么样呢?这就相当于给游戏增加了更多根“大棒”,但大棒的长度还是一样的。当你增加了更多根大棒,你就必须同时保证通过大棒的过程更有趣,或者让胡萝卜更加诱人。

例如,开发者可以说:“不错,你已经飞抵加拿大了。现在飞往中国吧。如果你到了,就奖励你一艘登月宇宙飞船。”在这种情况下,玩家可能会抱怨,因为眼前的挑战太耗时太费神了,而且必须重复已经做过的事,然后就此退出游戏。但另一部分玩家可能会为了宇宙飞船而决定继续砸时间。他们太想得到那根胡萝卜了,所以宁可接受更多的大棒。这是长期动机在驱使着他们。

避免“刷任务”行为

许多MMORPG,如《魔兽》,严重依赖长期动机来保持玩家的游戏热情。这通常导致玩家为了实现某个长期目标而不得不一次又一次地刷那些折磨脑细胞的任务。为了挣到足够的金子去买装备,玩家刷了150只半兽人,这就是一个完全依赖长期动机的典型例子。如果不是长期动机的支撑,玩家可能早就离开这款游戏了。

一开始,玩家觉得好玩,但完全掌握了操作后,唯一让玩家坚持下去的就是追求最终目标。这就是有意思的地方,尽管玩家内心觉得十分无趣,但他们仍然紧咬着游戏不放。长期动机的强大威力,有效地弥补了游戏玩法的日渐衰竭。

结语

保持游戏玩法和长期动机之间的平衡,是长久地保持玩家热情的关键。你不希望玩家离开游戏,但你同时也不想让他们玩你的游戏无聊到哭。最理想的情况是,开发者能将乐趣与长期动机相融合,创造出一个真正迷人的游戏世界,给予玩家流连忘返的体验。

游戏邦注:原文发表于2009年,所涉数据及时间以当时为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The Game Design Canvas: Long Term Incentive

by Brice Morrison

What makes a person want to continue playing a game? What takes a game from a 30 second experience to a 30 hour experience?

To answer this, we’ll have to start from the beginning: Why did the player begin playing the game in the first place? Fun and enjoyment are the most obvious answers. The thrill of the chase, the challenge, the quest! The opportunity to interact with others, to improve one’s skills, or to go on an adventure. All of these are examples of Core Experiences, which gets people to start playing a game. People want to have interesting experiences, and games are one way to fulfill that.

How about once they start playing, what does the player do then? They got there because they were seeking the Core Experience, and then they begin to enter into the game itself. They jump, they run, the roll dice, they make moves. They begin to interact with the game and perform actions within the game’s construct. Seeking an Experience, they are beginning with the Base Mechanics. They are beginning to become coordinated, so to speak, to learn to move and live in the game’s world.

Once they get going with the Base Mechanics, then they begin to learn the broader gameplay. They learn that they need to look before they jump, that they should treat villagers with respect when discussing delicate matters, and that they need to use the red bullets when fighting the red enemies. They begin to map out the interconnections between the actions they are making and the results the game is serving them. They are making their way through the Punishment and Reward Systems, learning what behaviors are encouraged and which ones aren’t. Building on top of the Base Mechanics, the P&R Systems draw them even deeper into the game and to the Core Experience they were originally seeking.

But then what?

After the player has learned the game, how it works, how it interacts with them, what makes them continue playing? What could cause a player to perform the same actions, the same strategies, the same rituals, over and over, yet enjoying themselves at every step?

Enter the fourth Game Design Canvas component: The Long Term Incentive.

Striving for a Goal

In well-designed games, the reason that players continue to play is because the player is seeking something. They are striving after a goal. The goal doesn’t need to be as explicit as you would think; it doesn’t even need to be very important to the player. In fact, the player may not even be consciously aware of the goal that is driving them. But there is a goal, an Incentive, for them to keep going after.

In Super Mario Bros., the player continue playing so that they can reach the next level and the next world. In classic coin-op games like Pac-Man, the Long Term Incentive is to get the highest goal possible. In exploratory games like Spore’s space stage or Knytt, the goal is to simply see what’s next, to make known the unknown. All of these are examples of a component in the design that drives the player onward, long after they’ve learned what they game is and how it works. A good Long Term Incentive can extend gameplay like no other component.

If there is no Long Term Incentive, then the game is not really a full game. These types of experiences are more like toys. The player explores the actions they can do (Base Mechanics), they investigate the relationships between the actions and feedback (P&R Systems), and they enjoy the content (Aesthetic Layout), but then they are…finished. There is nothing more to learn, nothing more to do. Everything has already been done.

A Toy Vs. a Game

Let’s walk through an example of this: Suppose you were walking on the street and you came across a small blue ball. ”Interesting!” you think. ”I wonder what happens if I push it?” You touch the blue ball and it magically hops forward. ”Wow! That’s interesting.” You then try touching it rapidly and find that it does not hop as far. ”It seems like if I want it to keep hopping, I need to time my pushes.” So you try this a bit more to prove your hypothesis, and it’s proven successful. You hop the blue ball around a little more, but then you grow bored and, having better things to do, move on to something else.

This is an example of a system with no Long Term Incentive. But by adding an Incentive, we can build this little blue ball into a game. Imagine that after you saw the ball, you saw a small blue box on the other side of the street. ”Hmm, it looks like I’m supposed to put this ball into the box!” Now you have Incentive. You hop the ball over to the box and inside. You have won the game.

Even though this example is a short one, notice what is extending the gameplay of this blue ball. No new Mechanics were added. No new Punishments or Rewards were taking place as you hopped the ball across the street. Instead, you had a goal that was driving your behavior, a goal that led you to complete the puzzle.

Some Common Long Term Incentives

There are vast arrays of Long Term Incentives in games. Some of the most popular are:

Complete all the levels. This Long Term Incentive was most popular in the early days of computer games, and still appear in many independent and main stream hardcore games today. The soldier must trudge and shoot his way through the war, or the intrepid monster hunter must save the kingdom, broken into chapters. The player completes each stage and, by virtue of another stage appearing, continues on and keeps playing. An older variation of this Incentive is the high score: since they player already has 115,876 points and can earn more by shooting one more Space Invader, they aren’t likely to quit not.

A more advanced method of Complete All The Levels integrates a scoring system into the stages, giving the player a Silver or Gold Metal, or perhaps a C, B, A, or S score. In this situation, the player will not only complete the level and move on the next, but be compelled to play each level again to get the best score. This advanced method is very close to our next popular Long Term Incentive…

Collect Everything. Some players are “completionists”, they can’t leave the game alone until every stone has been turned over and every treasure chest opened. If there is more in the game to collect, more to do, things to complete, then they won’t stop until it’s all done. Variations on this include completely leveling up your character to the maximum, finding all the special items, or collecting all the achievements.

Some games are very explicit with the Collect Everything incentive. Games that are very achievement oriented label each achievement. RPG’s may have lots of extra side-quests for the player to perform in return for better armor, weapons, etc. While these items aren’t required for the player to complete the game (Unless you’re doing a parody piece such as Achievement Unlocked), they do greatly extend the time a player is enticed to invest in a game.

Gain Information. Many games dangle new information in front of the player to compel them to continue. Story is an example of this; even if the levels in a tactics/strategy game grow monotonous, players will continue to learn what happens to Prince Leon, or their other favorite characters. Information may also be less explicit, such as seeing the end of a cavern or the bottom of an ocean, like in Flow. And yet as the player in Flow devours different sea creatures and goes deeper into the dark waters, they are compelled to go even further to learn what is down there.

Improve One’s Skill. Games like Street Fighter, Halo, or other action games bring along the Incentive to improve one’s own skill. This may be to clear incredibly difficult stages (a combination with the first common Long Term Incentive) or to be able to compete against other challengers. Players engage in the same battles over and over again, on the same stages, with the same weapons and moves, and yet they have a great time. That’s the Long Term Incentive at work. Sometimes these come with ranking systems. Halo, for example, ranks the skill of your performances in matches and then sets you up with other players of similar skill. This further encourages the player to improve themselves so that they can move up the ladder.

Selecting, Revealing, and Grouping Incentives

Long Term Incentives don’t necessarily have to be hours down the road. Anything that is driving the player forward in a meaningful way is a Long Term Incentive. It’s up to the developer to decide what kind of Long Term Incentive they want to put in their game. Some games seem incomplete because they have no real Long Term Incentive, while others only have a single Long Term Incentive. Many modern games have several long term incentives packed into the same space. This is a great way to give a game a professional level of depth. The game has many things to keep the player going, so that if they become bored with one Incentive, they continue playing because of another. This way, the developer creates a larger number of fail-safes in their Design Canvas, extra ropes that hold on to the player and keep them from falling away from the game.

In addition to selecting and grouping together Incentives, the developer also has the choice of how explicit to make them. A game that has very visibly placed Long Term goals, such as listing off achievements after each stage or giving the player a formal score, give a very different feel to games that do not do this. Games like Spore or Flow have similar goals to other games (complete the level, gain information), however they communicate this much less to the player. Rather, they let the player find their own goals and have a feeling that their following their own path. Hiding the Long Term Incentives from the player help the game feel less like a game and more like the Core Experience, but they run the risk of boring players who don’t understand what’s going on, or players who like to have their hand held and guided a little more.

Lengthening Gameplay: More Carrot, or More Stick?

The Long Term Incentive is the easiest way to lengthen gameplay and take a game from several seconds to several hours. However, developers need to be careful: leaning on the Incentive entirely to provide long term gameplay can be disastrous. Because of this, developers should be aware of how important the Long Term Incentive will be to the player.

A good analogy is the one of the carrot and the stick. The horse wants the carrot: the reward, or the Long Term Incentive. But to get there he needs to travel the length of the stick out in front of him: the task or the Base Mechanic gameplay. Perform the task, and he receives the reward. Crafting a good harmony of gameplay is the skill of crafting an effective carrot and stick.

If the Base Mechanics and the Punishment and Reward Systems are the solid focus of the game, then it doesn’t take much to keep the player interested in continuing. Having a design that forces the player to think, to engage one’s skills, and to execute over the long term is a designer goal worth having. But it is a challenge to keep this gameplay new and fresh over the long term. If your game is about flying an airplane, then it is easy to imagine a game where they fly from the U.S. to Canada. They would enjoy the first experience of learning how to fly, and feel a sense of accomplishment when they completed their Incentive by reaching Canada.

However, this experience isn’t likely to last long. What if that games needs to be longer, and they need to fly from Canada to China? They have added more stick to the game, but the stick is the same. And when you add more stick, you need to either make traversing the stick more fun, or make the carrot more desirable.

For example, the developer could say, “Good job, you’ve flown to Canada. Now fly to China. If you get there, you’ll get an entirely new rocket ship that can take you to the moon.” In this scenario, the player would likely groan, because the challenge set before them is so long and arduous, and is essentially repeating what they have already done. Some may just quit the game. But others would see that promise of a new rocket ship and decide to put in the time to earn it. They want the carrot so much that they will put up with the long stick. The Long Term Incentive propels them.

Avoiding the Daily Grind

Other games like this, such as many MMORPG’s like World of Warcraft, rely heavily on the Long Term Incentive to drive the player forward. This often results in what gamers refer to as “grinding”, performing the same boring, brain-dead task over and over again in order to achieve a long term goal. Fighting the same orc 150 times in order to gain enough gold to buy the silver armor is a great example of a game that is surviving almost entirely on its Long Term Incentive. If not for that, the player would have quit long ago.

The actions that the player is performing may have been fun at first, but after mastering them, the only thing that keeps the player going is the pursuit of that final goal. This is a fascinating situation because even though the player is bored out of their mind, they still grind away. Grinding is a great example of the power of strong Long Term Incentives, albeit used to compensate for weak lower gameplay.

Go for the Long Haul

Photo: Mr Malique

Learning to strike a good balance between the lower level gameplay and the Long Term Incentive is key to having a game that is compelling throughout. You don’t want your players to quit your game, but you also don’t likely want them to play your game while being bored to tears. Ideally developers can concoct a Design Canvas that allows for fun as well as long term gameplay, creating an immersive world and Experience where they don’t want to leave.(source:thegameprodigy)

上一篇:辨析“设计是法律准则”观念的谬误

下一篇:阐述提升游戏易用性的多种方法