分析导致冒险游戏题材没落的原因

作者:Tadhg Kelly

冒险游戏将在行业内逝去,这或许是最悲哀的事情。冒险游戏曾经盛极一时,但是在上世纪90年代中期开始没落,新千年到来之际它们在本质上已经死亡。但是它们却仍在发行商扬言将消灭这种题材的声音中苟延残喘。

冒险游戏为电子游戏这种艺术形式的发展做出了重大的贡献,但是它们逝去的根本原因在于:它们是劣质的游戏。

何谓冒险游戏

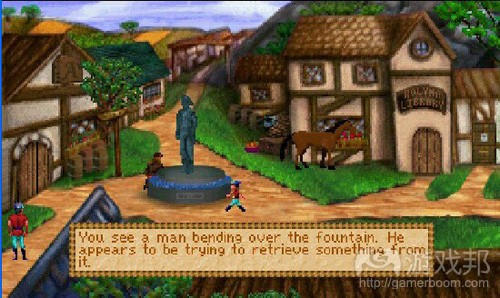

典型冒险游戏的基础是指向点击互动。玩家控制1个或者更多的角色,在游戏世界中来回移动,使用鼠标与各种角色和物品进行互动。游戏有个以故事为中心的架构,所以通常会有设定场景和玩家角色的介绍,使玩家熟悉整个剧情,同时产生某些构成整款游戏故事情节的动态冲突。

冒险游戏的玩法内容有寻找物品、搜集线索以及与相关角色交谈以获得各种解决谜题的信息。谜题通常很费解和隐秘,而从线索和暗示中得出下个任务也是游戏玩法的一部分。解决谜题推动故事向前发展,然后面对下个谜题,如此循环下去。通常情况下,故事被分作多个章节,剧情暂停以及地点或场景的改变就是分界线。

多数冒险游戏世界由一系列独立但是相互联系的屏幕组成。它们有着固定的镜头角度,玩家能够移动的区域也有限,这意味着它们实际上比其他游戏更像风景画。它们能够唤起人们的回忆,所以从理论上来说,在游戏世界中探索本身就是种奖励。

所有的这些特征使得冒险游戏成为未来故事叙述的最理想方式。但这也是为何它们是差劲的游戏设计的原因。

冒险游戏是劣质游戏

玩家首先需要弄清楚,要打开一扇锁着的门需要鱼骨,或者让看门人给你卷轴的方式是给他送个蛋糕,但是你必须首先找到密码才能说服烘焙师给你个蛋糕。

冒险游戏的基础通常是解谜。解谜需要依靠玩家的逻辑和直觉来发掘任务是什么、他们需要做什么以及如何使用他们已经收集的信息。事实上,你必须猜测出谜者的意图,才能够选择相应的正确答案。

在优秀的游戏设计中,失败可以被当成是学习过程的一部分。当你首次在《毁灭战士》中碰到恶魔时或许会死亡,但是你会意识到自己做了件错误的事情,就会在游戏中制定更好的战略。

解谜可以算作是一种不公平测试,正是这种不公平影响到冒险游戏的质量,通常达到难以玩下去的程度。它们所仰赖的隐藏只是显得模棱两可,缺乏能为玩家大脑所察觉的准确内在逻辑。

小部分玩家确实很喜欢这种解谜挑战,但是大部分玩家并没有。在面对失败的解谜时,普通的玩家会把它们视为一种排列的联系。他们尝试所收集到的所有物品直到找到正确的内容,不停地同所有角色对话直到正确的答案显现出来,用鼠标在整个屏幕中到处搜索可以点击的物品,或者寻找攻略来看接下来要做的事情。

因而事实上,他们变得非常繁忙。玩家四处行走通过对话获得钥匙,随后他们用获得的钥匙来尝试开锁。但是由于钥匙缺少红宝石力量的保护,因而损坏了(游戏邦注:玩家之前并不知道会发生这种事情)。所以,他必须回到之前的场景中再次进行同样的对话,再次获得钥匙和红宝石力量,然后去尝试开锁。冒险游戏总是充斥着此类的冗长任务。

这种类似作业的形式并不有趣,因为它将玩家当成每次将游戏进程推动一小部分的无足轻重之人。简而言之,它使玩家在想要做某些更具吸引力的事情的时候进行等待。玩游戏的本质就是获得推动改变的权利,无论这种改变是毁灭性的还是创造性的。从理论上来说,人们期望冒险游戏的故事能够产生那种改变。

多数玩家并没有打通整款游戏,这意味着故事并不是强大的驱动力量。如果故事有趣或者惊悚的话,那么确实能够为游戏增光添彩,但是它无法成为构建游戏设计的基础。作为讲述故事的媒介,电子游戏的作用同音乐差不多。二者都可以传达出某种故事感(游戏邦注:Jeff Wayne的《The War of the Worlds》确实很棒),但是当它们尝试在这个方面更加深入时,就会对趣味性产生影响。

当你最终不得不重复地听角色对话来寻找正确的线索时,故事的吸引力就会迅速渐少。游戏的重复性不可避免会产生厌烦感,就如同喜剧演员将某个笑话一成不变地讲上十次一样。玩的欲望位于倾听的欲望之上,但是冒险游戏开发者认为这种情况可以颠倒过来。

最终,冒险游戏没落的原因在于它是针对理想的玩家设计的,这些玩家不会为听到同样的系列故事感到厌烦并且是睿智的思考者。总之,这些游戏设计的目标受众就是这些开发者,而并非真实的玩家。

“视觉承诺”营销故事

冒险游戏粉丝通常认为,用户购买冒险游戏的原因是游戏的可玩性。从事行业零售这么多年,经历过这个题材游戏的风行和低谷,我认为事实并非如此。用户像以往那样购买冒险游戏是源于营销故事。

关键在于,要理解电子游戏出售的是它们的承诺而不是功能。《死亡岛》的表现展现了这种方法的有效性。这款僵尸游戏的精美预告片传达出了很多的内容,尽管评论不温不火,但游戏可能会销售火爆,因为预告片做出了很多的承诺。

行业通常会将这种富有吸引力的“图像”和工作室活动误解为同其他人的竞争行为。事实上,它是邀请玩家体验某些特别的经历。预告片或视觉效果用故事来引诱观看者体验游戏。它们似乎正在说:“想想你在这个世界中会有怎样的体验呢?”

这种“视觉承诺”营销故事也是为何冒险游戏今日依然流行的原因。《狩魔猎人》所做出的承诺确实很吸引人。许多冒险游戏也是如此。与16位主机游戏相比,冒险游戏看起来更加特别,或许更为成熟,更有可能在市场上引起轰动。CD-ROM之类的技术使用全动感视频内容使得承诺得到增强。

那么,为何它们会死亡呢?它们只是被其他类型的游戏超过了而已。或许从《毁灭战士》发布之日起,其他游戏的视觉效果就可以同冒险游戏向媲美。它们也都能够3D化,有着更逼真的环境效果,使用更棒的音效和图像类型。而且这些新游戏有着冒险游戏所不具有的特点:它们能够发展。

此前,16位主机游戏和PC游戏的质量都不高,而冒险游戏达到了最高的质量,从而赢得了市场。但是,当与PlayStation上的游戏相比时,它们就显得乏味了。《Ocarina of Time》以及许多其他游戏同样展示冒险,并且以某种指向点击式冒险游戏无法做到的方法来设计游戏。

既然玩家能够探索地下城、设计恶魔、驾驶汽车或者体验到其他3D游戏更具鲜活性的内容,那么谁还会愿意到处跑动来解谜呢?当动作游戏横空出世,冒险游戏就像是无声电影,这种只有对话的游戏世界和拙劣设计的限制性注定了它们的悲惨命运。

冒险游戏的贡献

尽管它们已经逐渐没落,但是冒险游戏确实为游戏行业做出了卓越的贡献。

角色扮演或惊悚生存等题材的游戏从冒险游戏中学到了很多内容。《失忆症:黑暗后裔》等游戏能让我们回想起那个时代,我们可以在许多游戏中看到冒险的元素。Agatha Christie系列的隐藏物品游戏从本质上来说是冒险游戏,只是抛弃解谜并且更清晰地使用故事感而不是讲述故事。

冒险游戏还展示出了语音的重要性。那些有着最棒的剧本、最有趣的角色对话和场景的冒险游戏最让人印象深刻。对于游戏而言,剧本是整合精灵并且使得单纯的趣味性更为特殊的最佳方法。许多开发者都还没有意识到这一点。

最为重要的是,冒险游戏同电子游戏受众的艺术品位直接对话,这是其他游戏在其时代所缺乏的。冒险游戏让许多开发者产生了可以构建丰富世界的想法,所以在许多方面它们为设计师的灵感指明了方向。

尽管冒险游戏作为游戏来说很不尽如人意,但是它们可以成为游戏的愿景。它们有自己统治行业的时代,也会被更好的游戏所替代,然而开发者还是不该忘记制作某些更大更深层次的东西。

游戏邦注:本文发稿于2011年6月9日,所涉时间、事件和数据均以此为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Adventure Games Deserved To Die

Tadhg Kelly

Perhaps the greatest lament of all is the one about why the adventure game died. Once hugely popular, adventure games started to fall out of favour in the mid 90s and by the turn of the millennium were essentially dead. However they did not die because of a grand conspiracy on the part of publishers to kill them (as is often asserted).

Adventure games contributed hugely to the development of the video game as an art form, but there’s a basic reason why they went away: They were bad games.

What Adventure Games Are

The typical adventure game is based on point-and-click interaction. The player controls one or more dolls, walking around the game world and interacting with various characters and objects within it using the mouse. The games have a story-centric structure, so there’s usually an introduction to set the scene and the character of the player, familiarise him with the scenario and set up some dramatic conflict which then establishes a plot for the whole game.

The gameplay of adventure games is all about finding objects, obtaining clues and talking to relevant characters to acquire various bits of information to solve puzzles. Puzzles are frequently obscure or cryptic, and part of the gameplay involves intuiting next task from hints and allusions rather than being given a to-do list. Solving a puzzle nudges the story along, to the next puzzle and the next and so on. Commonly that story is broken into chapters with dramatic interludes, changes of location or scenario.

Most adventure game worlds are constructed as a series of separate but interconnected screens. They have fixed camera angles and limited areas in which the player can move, which means they often look more picturesque than other games. They can be evocative, cinematic, and so in theory the exploration of the world is itself a reward.

All of this makes adventure games the genre that most closely relates to the narrativist ideal of games as the future of storytelling. But it’s also why they’re an example of really bad game design.

Adventure Games Are Bad Games

The player has to figure out that the way to open a locked door is with the bones of a fish, or that the way to get the gatekeeper to give you a scroll is to bring him a cake – but you have to convince the baker to give you a cake first by finding a passphrase.

Adventure game puzzles are commonly based on riddles. Riddles rely on player logic and intuition to realise what the task is, what they need to do and how the information that they have collected fits into a pattern. In effect, you have to guess the intent of the riddle creator in order to understand where he’s coming from, and then select the correct answer accordingly.

In good game design failure is a part of the learning process. When first encountering cacodemons in Doom you might die, but you can sense what you did wrong and charge back into the game with a better strategy. In an adventure game it tends to be all or nothing.

Riddles are an example of an unfair test, and it’s this unfairness that makes adventure games bad, often to the point of unplayable. They rely on hidden knowledge, are deliberately ambiguous, and lack a sound internal logic that the play brain can perceive.

A small minority of players genuinely love the challenge of riddles but the vast majority don’t. Faced with failing a riddle, the average player will treat them as an exercise in permutations instead. They try all of the objects in their inventory until they stumble onto the right one, have all the conversations with all the characters over and over until the right answer presents itself, scan the screen back and forth with a mouse pointer to find clickable objects, or go in search of cheat guides to tell them what to do next.

So in effect, they descend into busywork. The player walks from one place to another to have a conversation to obtain a key. He then walks to another place to try the key in a lock. However the key lacks a ruby of strength to protect it (which he didn’t know about) so it breaks. He then has to go back to have the same conversation again, get another key and a ruby of strength, and then come back to the lock once more. Adventure games are full of this sort of tedium.

Busywork is not fun because it treats the player as a cog that nudges the game along every once in a while in the name of fun, rather than as the agent of change that he wants to be. It makes the player wait, in short, when he wants to be doing something more engaging. The whole point of play is to be empowered to cause change, whether destructively or creatively. In theory the story of the adventure game is supposed to be that change, but if it is it’s the least engaging form of change there is.

Most players never finish games, which indicates that story is not a strong motivator. It’s nice to have if it’s funny or scary, but not something to base your game design around. Video games are not really a storytelling medium any more than music albums are a storytelling medium. They are both great at delivering something of the sensation of a story (for example, Jeff Wayne’s The War of the Worlds is fantastic), but they run into the brick wall of a lack of interest when they try and push beyond that.

When you end up having to listen to the same snippets of character dialogue over and over to find the right clue, story’s appeal quickly wears thin. It takes a fearsomely funny writer to allay the sense of boredom that inevitably descends when a game becomes repetitive, and even then the effect can be similar to watching a stand up comedian tell the same joke ten times in a row with no variation. The desire to play overrides the desire to listen, but adventure game developers wanted to believe that those desires could be reversed.

Ultimately the reason why the adventure game is fundamentally flawed is that it is designed for an ideal player who never gets bored of hearing the same story sequences and is a brilliant intuitive thinker. They are, in short, designed for the developers themselves and not real players.

The ‘Visual Promise’ Marketing Story

Adventure game fans often assume that customers bought adventure games because of their gameplay. As someone who worked in the retail side of the industry during the heyday and death of the adventure game, I would say that is not the case. Customers were buying adventure games, as they usually do, based on a marketing story.

A crucial thing to understand about videogames is that what sells them is their promise, not their features. Dead Island has shown the effectiveness of this approach.

It was the zombie game with the gorgeous trailer masking an average message that I wrote about earlier in the year, and despite tepid reviews will probably sell well because that trailer promises so much.

The industry often mistakenly labels this appeal ‘graphics’ and studios rush to compete with each other in terms of brute force performance. What it actually is is a marketing story which invites the player to experience something special. Trailers or visuals simply tantalise the viewer with that story. ‘Think about what you might get to do or experience in this world’, they seem to say.

That ‘visual promise’ marketing story is why adventure games were popular back in the day. The promise of Gabriel Knight (to take a random example) was intriguing.

Ditto for many other adventure games. Compared to 16-bit console games, adventure games appeared special, more grown up perhaps. More about something than just hitting stuff. Technologies like CD-ROM strengthened that promise with full motion video content.

So why did they die? They were simply outclassed. Perhaps starting with Doom (or thereabouts), other games started to look as good as adventure games. They went 3D, had more immersive environments, used better sound effects and graphical styles that weren’t juvenile. And these new games had an advantage that adventures games lacked: They moved.

16-bit console and PC games had always had a static quality and the adventure game maximised on that quality to create beauty. However when compared to a PlayStation demo or Mario 64 they looked stuffy and intellectual. Ocarina of Time and many other games showed the player adventuring and doing stuff in a way that point and click adventure games couldn’t match.

Who really wanted to run around solving puzzles to open doors with herring bones when they could be exploring dungeons, shooting cacodemons, racing cars or any of the other more lively pleasures that 3D gaming embraced? When action games sprang to life the adventure game became the equivalent of the silent movie in a world of talkies and the limits of their poor design sealed their fate.

The Legacy of Adventure Games

Despite their flaws, adventure games positively contributed to games as they have become today.

Other genres, such as the roleplaying game or the survival horror, have gained much from the adventure game. Games like Amnesia: The Dark Descent have a sense of heritage back to the old days, and we see adventure-lite elements in many other games. Hidden object games like the Agatha Christie series are essentially adventure games without the riddles and with a much clearer use of storysense rather than storytelling. And there is the joy of delightfully canned games like the Phoenix Wright series.

Adventure games also demonstrated the importance of voice. The most fondly remembered adventure games are the best written ones, with the most interesting character dialogue and settings. Writing is one of the best ways for games to incorporate numina and rise above the merely amusing to become special. This is a lesson that many developers never learn, to their cost.

Most importantly, adventure games spoke to a taste for art in video game audiences that other games of their era lacked. They left many developers with the idea that they can construct rich worlds, not mere mechanical bulls, and so in many ways they serve as a powerful example of where inspiration can truly go.

Although adventure games were bad as games, they were great as visions of what games might be. They had their time and they were outclassed by much better games, yet the desire to make something larger and deeper is one that should never be forgotten. (Source: What Games Are)

上一篇:关于提高应用商店曝光度的经验分享

下一篇:游戏设计师应是科学家而非炼金术士

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号