分析游戏开发团队管理者的作用和重要性

作者:Rampant Coyote

在我的游戏开发生涯早期,我很幸运能够与一些优秀的制作人/管理者共事。后来,在我的其它工作中(也包括一些与游戏产业无关的工作),我便再也没有遇到这种运气了。几天前,为了回应关于一些有趣报道所做出的评论,我们就游戏产业中一些制作人展开了激烈的讨论。Late White Rabbit,这位有着丰富商业经验的元老甚至质疑那些管理者和制作人的存在价值。

当我在发行第一款独立游戏时,最让我感到震惊的是时间问题,特别是在游戏发行后期,我花费于游戏管理的时间竟然远远多于我的想象。原本我以为作为独立游戏开发者,只有一个很小的团队(再加上外包人员的帮助),我将不会遇到这些繁琐的问题。但是事实并非如此,所以我想在此与你们分享我的亲身经验,谈谈我理想中的管理模式。在游戏发行后期,我花费了大量的时间发电子邮件给外包人员并与他们进行沟通,与电子商务公司和发行网站签订相关文件,制定出游戏发行计划和市场营销策略(显然我在这方面做得不够好,因为我的游戏并没有赢取多大的市场效应),接受记者的访谈,致力于网站上的完善等等。

对于独立游戏开发者来说,这些都是很有帮助的。

首先我们来说说一些理论上的问题。这些观点都是显而易见的道理,你可能也已经对此颇为熟悉。

作为独立游戏开发者,你总是单独行动。你擅长于所有东西。我讨厌所有像你们一样有才能的人(当然,这只是出于一种嫉妒心里)。不管怎样,作为一名独行侠,你可以将一整天的时间投入于游戏中(把游戏开发当成全职工作或者边兼职边制作游戏)。让我们把工作量称作“zot”。即你的产量是1.0zot,你的游戏获得1个完整的zot。

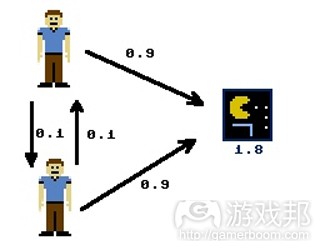

现在让我们假设你擅于游戏编程但是却不擅美工。而这时候你的游戏开发过程的效率可能只有0.25zot。而如果可以不受关卡设计,对话等因素的影响,你将可能获得完整的游戏生产率。不论是什么情况,如果你有一个合作伙伴,那么情况都将有所改变。当你的团队中有2个人一起开发游戏时,是否效率就会较之前快了1倍?不一定。只要你的的开发团队多了一个人,你就需要挪出更多的日常开支于彼此间的沟通与交流。这需要0.1zot的代价。但是相信我,比起那些未进行交流和沟通而引起混乱的团队来说,这种代价真的小太多了。就像我之致力于Jet Moto项目时发现,团队里的成员们对于游戏具有更多不同的观点,而因此导致最终制作出来的游戏与他们预期的游戏设置(和编码)相矛盾。

不管怎么样,你现在将花费0.1zot与团队交流和协作,并投入0.9zot于游戏中。那么游戏便得到了1.8zot的总投入,而如此平均分摊到2个人的身上也正为合适。

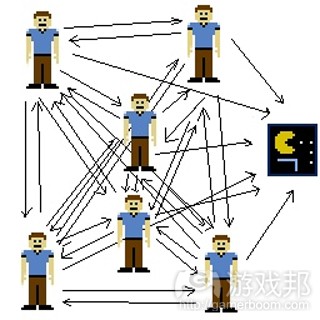

如果增加到3个人又是什么情况呢?即一名设计师兼测试者,美工者和程序员。每个人花费0.1zot于彼此间的交流,并留下0.8zot给游戏。即他们每天总共花费2.4zot于游戏中。以此推算,4个人就变成2.9zot,5个人是3.0zot(5*0.6=3.0)。当团队人数变成6时,结果与5人是一样。每一名成员花费0.1zot于交流和协作中,就等于他们花费了0.5zot于日常开支上而只剩下0.5zot于游戏中,所以他们每天花费于游戏中也只有3.0zot。

为何提升到5人的团队成员结构也没有让结果得到改善,甚至更糟?当团队成员提升到6人时,生产率甚至下降到与5人相当的境况。

也许我这种数字分配方法并不妥当,在现实中人们也许会花费更多时间与部分人交流,而没有与另一部分人进行沟通,但是,根据我的经验,这种人员分解经常是从4至6名团员变化开始。一旦你的团员从2名开始往上增加,你的团队政策将会发生相应变化。民主政策将能够帮助你的团队成员和平共处,但是它们却不能帮助你提高工作效率。你的团队拥有更多不同角色的成员,你将面对更多潜在的风险,并且在情况还未变得最糟糕前你未能发现这些风险。

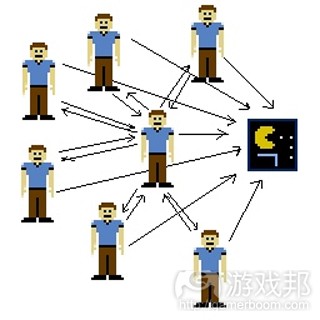

而这时你就需要采取一些管理工作。你按照等级结构去区分一些事物,如上图所示那样,我们现在有7名成员,但是他们只与制作人(比起进行单纯的交流,他的作用是推动其他成员间的沟通)进行交流。所以再次,增加第7名成员以充当制作人的身份,将形成6*0.9=5.4zot。而因为制作人本身还有0.2zot可以直接用于游戏本身,最终的工作效率便可想而知了。

对于那些同时开发两款游戏的大团队来说,这种方法更为重要。随着工作室的发展,你的游戏在开发过程中将会需要不同的人力。而让一些人站在较高的级别去明确更多工作和资源需求,将会对你的游戏开发更有帮助。

显然的,比起那些有一名成员单纯地进行着“管理”工作的策略,这种方法看起来好多了(游戏邦注:小团队尤其如此)。但是这个也只是用于解释为何3,4名成员以上的团队不适用于平面模式,而需要采取等级模式的一种理论观点。不管怎么样,如果你的团队中有一名优秀的制作人,能够帮助你管理好整个团队,那么这就是最好的实际理论。以下我将根据自己所遇到的情况谈一些个人观点/理论。

首先是关于管理人员的等级或者位置。这是一个很棘手的问题。这就是为何我图上所有成员是围绕着管理者而非位于其下方的原因。我认为(特别是在一些小公司里),管理人员在薪资/级别上应与其他团队成员相同,或者至少不能在所有“利益相关者”之间“搞特殊”。不过小团队聘请他人扮演管理者角色的情况也并不鲜见。我承认,没有权威的管理者确实比较头疼。但是我并不认为这是“领导者”所需要的唯一一种才能,我认为,作为一个团队中的管理者,他还必须对自己所领导的成员们负起责任。

其次,在一些小团队(或者特别是在一些小团队)中也有一些领导角色。并非意味着所有人都要听这个领导角色的话,而是指他能承担起团队中的相关责任。这个人将是游戏的领导者/管理人/制作人等等。不论什么时候,只要是1个人以上的团队进行任务,那么他们就需要一个与任务相关的领导。你将会有美工领导,编程领导,设计领导,市场影响领导,业务处理领导(特别是在与第三方或者发行商签订合同时)等等。你可以派遣团队中的一人担当领导角色。这是很多独立游戏开发者所采取的措施,即让一个人承担起领导任务,并签订一系列合同条约等。

不管怎样,这种领导者的角色始终存在于团队中,甚至是对于那些需要扮演不同角色的独立开发者而言也如此。需要有些人去确认游戏的发行时间是否适当,确保所有的开销不会超过预算,并保证游戏的质量能够满足玩家的需求。换句话说,这个领导者正是带领整个开发团队走向成功的重要角色。这个人既需要有足够的威信,也需要有准确的判断力。任何决定都不能只是停留在表面工作,需要一个人来做最终的决定。

我所钦佩的团队领导者/管理者需要管理各种琐事。不论他是谁,作为领导者,他最好能够扫清阻碍游戏成功的各种障碍,解决团队美工和编程成员间的争吵,决定是否购买帮助提高生产力的新工具等等。

不幸的是,就像Late White Rabbit的评论中阐述的,即使在整个软件产业里这种领导者也不算是一个完整的“产业标准”,更别说在单单一个游戏产业里了。反倒是这些领导者所做的事经常有悖于我们的期待。他们频繁地召开会议只是想让让人觉得他们很忙,其收集一些信息则是希望能对上级有所交代。他们对一些小事情吹毛求疵,但是对于一些大事情却往往不敢下决定。更糟糕的是,他们总是扮演着暴君的角色,不经过团队其他成员的同意便妄自下决定。最可怕的是,他们常常不把自己当成是团队中的一员,总是想着如何做才能逃避团队中的争执。

游戏邦注:原文发表于2011年2月23日,所涉事件和数据均以当时为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

What Does a Game Producer / Manager / Leader Actually Do?

Posted by Rampant Coyote on February 23, 2011

When I was in the trenches of game development early in my career, I was lucky enough to have some producers / managers who were pretty good at their job. Later on, in other jobs (including many outside of the games biz), I wasn’t always so lucky. A couple of days ago, in response to my little commentary on interesting bug reports, we got into a lively discussion about some producers in the games biz who are pretty much useless. Late White Rabbit even asked – as an experienced Marine with a business degree – questioned the value of managers or “producers” (as they were called in my first company) at all.

One of the things that really shocked me when I released my first indie game was how much of my time – particularly during the latter stages of the project – I spent doing “management” type things. Here I thought, as an indie with a principle team of one (plus contracted help), I’d be rid of that entirely. So I figured I’d post on this – based on my experiences (good and bad), and my ideals of what I think management SHOULD be like in my own little imaginary world. But I was spending a lot of time emailing or talking to contractors, signing paperwork with e-commerce and distribution sites, working out launch & marketing plans (evidently I didn’t do so well, as the game was never a big seller), talking to journalists, working on the website, etc.

So this is valuable stuff for indies, too.

First – a quick review. How things work in theory. These lessons come directly from Mount Obvious, so you should already be familiar with them.

Let’s say you are a “lone wolf” developer. You are really good at just about everything. I hate talented guys (and gals) like you. ![]() (Actually, I want to be a guy like that, but I hide my aspirations with jealousy.) Anyway, you the lone-wolf can devote your full attention in a day to your game – whether that’s a full-time day, or a 2-hour evening working part time, doesn’t matter. Let’s call that amount of work a “zot.” So your productivity is 1.0 zots, and the game gets the full zot. Life is awesome. Ain’t being a lone-wolf indie grand?

(Actually, I want to be a guy like that, but I hide my aspirations with jealousy.) Anyway, you the lone-wolf can devote your full attention in a day to your game – whether that’s a full-time day, or a 2-hour evening working part time, doesn’t matter. Let’s call that amount of work a “zot.” So your productivity is 1.0 zots, and the game gets the full zot. Life is awesome. Ain’t being a lone-wolf indie grand?

Now lets say you are awesome at programming, but not so good at art. Maybe that part of the game development process only has you operating at 0.25 zot efficiency. Or maybe you think you can only achieve your full productivity if you don’t have to be distracted by things like level design, dialog, and so forth. Whatever the case, you decide it’s best if you have a partner. Now there’s two of you working on the game. Should get things done twice as fast, right? Well, not quite. As soon as you have other people working on the game, there’s some overhead introduced involving communicating and coordinating with each other. Let’s say it’s a cost of 0.1 zot. Believe me, it’s cheap compared to the alternative – major, major disasters have been caused by teams NOT paying that cost and the project descending into utter chaos. While not a disaster, we ran into similar issues when I was working on Jet Moto, where some team members had a different vision of the game than others, and ended up generating assets that were totally incongruous with the expected gameplay (and code).

Anyway, both of you are now spending 0.1 zot coordinating and communicating, and then putting 0.9 zots into the game. Now the game is receiving a combined total of 1.8 zots, for 2 people. Not too bad.

Rev it up to three people – say a designer who is also taking on the role of tester, an art guy, and a programmer. With everyone spending 0.1 zot talking to each of their other two team members, that leaves them 0.8 zots working on the game . That’s 2.4 zots spent per day on the game, total. Four guys, the total is 2.9. Five guys, it goes up only a tiny bit, to 5 x 0.6 = 3.0. And then… we bring the team size of six people. same values. If every team member is spending 0.1 zot coordinating and communicating with the other five members, then they are spending 0.5 zots on overhead, and only 0.5 zots on the game itself – for a total of still only 3.0 zots per day.

What? No improvement at all over a team size of five guys? And it gets worse! As the team size expands above six, productivity drops even more with a flat team hierarchy.

I may be pulling numbers out of the air, and in reality guys may spend more time talking to some and not to others, but in my experience the break-down usually starts occurring somewhere between four and six team members where “flat” fails. Also, once you get more than two people involved, politics may happen. Democracies are great for getting people to coexist freely and peacefully with each other, but they don’t work well for getting a job done. And the more people you have with different roles, the more potential there is for something “falling through the cracks” and not getting done until it’s a bad, expensive surprise.

And that’s where you get some kind of management involved. You break things into a hierarchy. Even something as dumb as the picture to the left will work — now we have seven people working, but only “talking” to the producer (who is probably, in reality, facilitating coordination between members rather than just acting as a single point of communication — this is all theoretical here…) So in this example, adding a seventh person as the producer theoretically brings everybody up to 6 x 0.9 = 5.4 zots. And even the producer may have 0.2 zots left over to do some direct work on the game himself, right?

This gets even more important with larger teams that may have two projects in development at a time. As studios grow, this is key, as games have different manpower needs during development. Having someone at a higher level who can perceive the “greatest need” and shuffle resources as needed can be very helpful.

Obviously, there are probably much better ways of doing this that would be cleaner than having one dude doing little more than just “managing,” especially for a very small team. But this was a theoretical exercise to illustrate about where a “flat” model breaks down very quickly, and why some kind of hierarchy gets needed after about three or four people. Anyway, that’s the basic theory, if you have a good producer managing a team. Now we’re going to some personal theories / ideals of my own - based loosely on what I’ve seen work.

First of all – the rank or position of the manager. This is a tricky situation. And this is why I drew the picture with the team surrounding the manager instead of being “under” him. I do believe, especially for small companies, that management should be pretty much equal in pay / rank to the rest of the team – or at least no different from any of the other “stakeholders.” It’s not unheard of that a small team might actually hire someone to manage them – making the manager their employee. I do acknowledge that the lack of authority may cost them some of their tools. But I do not believe that is necessarily the case, and I think there’s something inherently healthy about the “leader” of a team also being answerable to the people he leads.

Secondly – there are lots of leadership roles on even a small team. Or maybe especially on a small team. Not all belong to one person, but I do believe there should be one person for whom the buck stops with them. That person is the project lead / manager / producer / whatever. But whenever more than one person may be involved in a task, one person should have the leadership role related to that task. You have the art lead. The programming lead. The design lead (or “keeper of the vision.”) Someone leading marketing efforts. Someone handling the business end of things – particularly when it comes to setting up contracts with third-parties or distributors. You could have one person doing that role. For many indies it comes exactly down to that, as there’s one person running the show and working with contractors.

But the role is always there, even for lone wolves who must wear a dozen hats daily. Someone needs to be making sure the project ships in a timely manner, doesn’t blow its budget too badly, is of reasonable quality and addresses the needs of its intended audience. In other words, they have to lead the team to success. Someone needs to have both the will and the authority to cut features and make other hard decisions necessary. It shouldn’t be done in a vacuum, but someone has to have the final say.

One final role I admired in team leads / managers was to be the “mother hen.” This person, whoever they are, may also be in charge of removing obstacles to the team’s success – whether it is in internal argument between art and programming, or deciding whether or not to buy a new tool for the team that would theoretically boost their productivity.

Unfortunately, as Late White Rabbit noted in his comments, this isn’t all “industry standard” even in the software industry as a whole, let alone the games biz. Too often they end up doing the opposite of what I feel their jobs should be. They create long meetings to feel busy and collect information so they can report to their own superiors as if they actually knew what was going on. They nitpick the small stuff, and are afraid to make a decision on the big stuff. Or worse, they play tyrant, and make fiat decisions without gathering information from the rest of the team. And worst of all, they don’t seem to consider themselves part of the team, but rather someone aloof to the fray.(source:rampantgames)

上一篇:游戏设计无捷径 迭代方法是关键

下一篇:开发者不可重游戏玩法而轻图像设计

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号