调整游戏难度设置有助于吸引广泛用户群体

作者:Lars Doucet

作为正准备发布的RPG游戏《Defender’s Quest》的部分内容,我将在下文中讨论RPG、挑战性和“刷任务”。首先,让我们从游戏的易用性开始。

易用性

易用性是指移除障碍来增加游戏的用户数量。

许多游戏只适用于拥有良好的视觉、听觉、反应以及双臂和十指健全的用户。通常来说,这些身体需求都是主观的,游戏可以重新设计成那些有视觉障碍、听觉障碍、反应缓慢和只有一只手的玩家也能够通关。上述这些目标并非很难或需要花费大量金钱才能实现,在游戏中添加某些简单的功能即可,比如自定义控制、可调节的游戏速度以及服务色盲玩家的视觉选择。

当然,你无法添加所有的内容。比如,要让盲人可以玩上图像密度较大的游戏就很困难,就像要让四肢瘫痪的人爬山一样不现实。

但是,无法接触某些游戏的并非只有残疾人这个人群,肢体技能也是障碍之一。由于游戏的难度较高,许多正常玩家也不得不放弃本可以从中享受到乐趣的游戏。

难度

难度可能是人们无法完成某个游戏的几大原因之一。正如移除对肢体技能的要求能够使游戏获得某些残疾用户一样,降低难度能够让游戏获得更多的低硬核玩家群体。但是,游戏要采取何种方式才能在不影响体验的前提下降低难度呢?

超高难度和硬核游戏通过易用性扩展用户的完美例证是《VVVVVV》。

易用性选项允许你放慢游戏速度,开启和关闭视觉效果,甚至将自己设置为无敌状态。这些选项帮助游戏获得残疾和休闲玩家的青睐。看到此等硬核游戏中有这些功能令人感到惊奇,在这个许多开发商大肆吹嘘自己所开发游戏的难度(游戏邦注:比如《恶魔之魂》之类的游戏)的年代里更是如此。

因为我的残疾(游戏邦注:本文作者患有猝睡症和妥瑞症)不会影响到我玩游戏的能力,所以我通常选择常规设定。对我来说,放慢游戏节奏或让自己无敌会完全“摧毁”游戏体验。所以你可以想到,我并没有打开这些特别功能。

我玩这款游戏并从中获得乐趣。而且,游戏有难度较高的模式和某些他人觉得过于简单的挑战。这些可以通过玩游戏来逐步解锁,但是如果需要,你也可以通过主菜单自行解锁这些内容。就个人而言,我喜欢通过自己的努力解锁内容带来的成就感。所以你可以想到的是,我并没有通过菜单来解锁。

但是,我能肯定有某些玩家讨厌被迫通过自己的努力来解锁他们已经付费购买的内容,所以他们会立即爱上这个额外的功能。这个选择又解决了另一个争端,所有人都可以获得胜利,只要“胜利”的定义不是“强迫每个人以同样的方法来玩游戏”。

为其他玩家移除障碍,甚至为他们添加特别的功能,丝毫不会影响到游戏对我产生的乐趣。反而,我获得了我想要得到的体验,而且许多其他玩家也是如此。这使得游戏的核心设计能够触及更多的人群。我曾听过许多硬核玩家声称,所有花在提升游戏易用性的精力都应该花在提升游戏质量上。这种说法不仅不恰当,我还觉得所有支持更多玩法风格的做法也可以算作是优化游戏之举。

但是更为重要的是,这里好像出现了某个有趣的原则:玩家自然会选择与他们能力相符的挑战水平。

由此必然会出现以下结果:

1、如果游戏过于简单,玩家会尝试让其更有挑战性。

2、如果游戏难度过高,玩家会尽量把它变得简单。

我觉得游戏设计应该达到的目标是,所有玩家想让游戏变得更简单或更难的工具都触手可及,而不是强迫玩家采取作弊码和自定义mod手段来获得适合他们自身的体验。而实现这个目标的方法应该不会冒犯玩家或者降低他们的期望体验。

那么,这与RPG游戏、刷任务和《Defender’s Quest》有何关系呢?

刷任务

刷任务是游戏领域历史最悠久的易用性选项之一。如果玩家无法击败下个BOSS,那么她可以去击败其他低级怪物获得升级,然后再次尝试。这方便了不同技能等级的玩家以自己的方式来实现相同的游戏任务。

尽管玩家在《最终幻想》中可以在推荐的35级时打败最终BOSS,但是当年仅有8岁的我还只是个菜鸟,不得不升到50级才获得了击败BOSS的机会。这并非完美的解决方案,但是确实提供了合适的“安全阀门”,确保游戏中不会出现不可能实现的目标。回顾所有电子游戏的过场动画带来的非凡体验,RPG游戏是我唯一期望能够打通的游戏类型。

就其好处而言,刷任务确保玩家只需要不断玩游戏就可以获得胜利。

就其坏处而言,刷任务人为地扩展了游戏的长度,通过斯金纳原则和令人上瘾的机制来控制玩家(游戏邦注:就像某些Facebook游戏的做法)。

刷任务好坏共存。

之所以说它存在不益之处,是因为它惩罚那些较弱的玩家,迫使他们必须花更多的时间完成任务,而且这部分人的闲暇时间往往很少。而且,刷任务本身通常都很乏味单调。

但是,这种设置也有好处,因为它让玩家只需要通过玩游戏就可以平稳地调整游戏的挑战,完全无需做足准备工作。刷任务不仅为休闲玩家降低了难度,拒绝刷任务还可以让硬核玩家提升游戏难度,比如尝试在25级时打通《最终幻想》。

如果处理得当的话,游戏的挑战可以由玩家自行调节。随着玩家在游戏中进行下去,他们很自然地会去上下调整挑战水平。

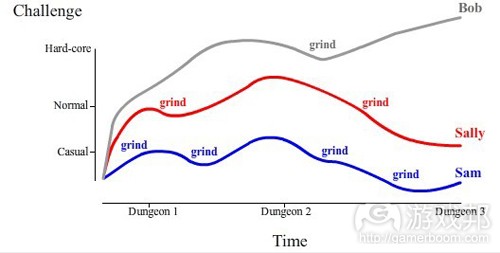

Sam是个技术低于设计师想象的玩家,其水平甚至低于游戏所指向的“休闲”玩家。因而,Sam在整个游戏过程中都需要通过刷任务以降低自己遇到的挑战。Sally刷了一小段时间的任务,将游戏挑战保持在“正常”的水平。而Bob拒绝刷任务,他尽量提高挑战门槛。

现在,让我们看看如果移除了刷任务选项会对Sam的体验造成何种影响。Sam现在必须在游戏开始时从“简单”、“普通”和“困难”三个难度模式中做出选择。因为技能较弱,Sam会选择“简单”模式,然而却发现多数关卡对他来说仍然太难。游戏设计师通常对“简单”难度的把握不当,所以当我怀着“简单模式肯定会很简单”的念头进入游戏是会发现事实并非如此。

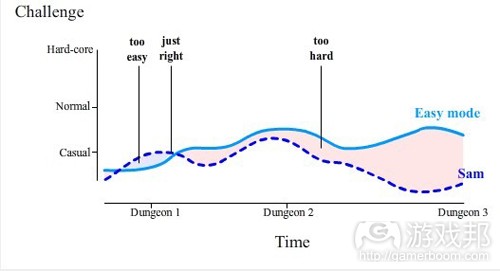

深蓝色曲线呈现的是Sam希望取得的关卡挑战,但是由于不存在刷任务,除了遵从游戏中所谓“简单”模式的难度曲线外他别无选择。由于没有进行调节的方法,Sam很可能在体验首个地下城环节之后就会很快地离开游戏。

动态难度调整

除了刷任务外,对这个问题的普遍解决方案是“动态难度调整”,即所谓的DDA。在这种方法中,游戏根据玩家在游戏中的行为来调整难度。最早使用这种方式的游戏之一是街机射击游戏《Dragon Spirit》。在这款游戏中,首个关卡是个隐藏的测试。如果你死亡了,随后的游戏就会是“简单”模式。如果你在首个关卡中存活下来,那么你将进入的是“普通”模式。这种做法很大程度上并未被玩家察觉。

当然,当玩家发现这个规律后他们会觉得自己受到了欺骗,可能的应对措施是在首个关卡中死亡后就重置游戏。诸如《战神》和《恶魔猎人》等游戏采用的DDA方法是让玩家在死亡数次后自行选择较为容易的难度模式,这种做法可以解决上述问题。这种做法将控制权交回玩家手中,但有时感觉像是种嘲讽玩家无能的侮辱。

DDA能够起到作用,但是并不完美。问题在于,任何预先设定的难度模式永远都无法匹配玩家个人不同的挑战曲线,而游戏中难度的转变有时仅仅意味着在“太难”和“太容易”间做出选择。

刷任务并不能在所有题材的游戏中发挥作用,就RPG而言我更偏向刷任务而不是DDA。这两种方法都可以降低游戏的难度,但是刷任务至少让我觉得我做了些事情。DDA只让我觉得自己是个输家,需要选择较容易的难度。

玩家驱动的目标

难度问题的另一个解决方案是让玩家自行设定目标。《Donkey Kong Country 2》(游戏邦注:下文简称DKC2)便是个绝佳的例证,David Sirlin曾对此进行解释。总结如下:单纯打通DKC2是“相当简单”的,但是找到所有的秘密并获得100%的完成度很困难,玩家可以自行选择想要获得怎样的目标。通过这种方法,DKC2让玩家自行绘制难度曲线。当玩家觉得游戏“太容易”时,她可以选择去寻找更多的秘密来深化挑战,但是当游戏显得“太难”时,她可以只把打通关卡作为目标。

我只对David的某个小观点有异议,那就是打通DKC2是“相当简单”的,要么就是我和妻子十分不擅长经典电子游戏。无论出于何种原因,我的观点是只要玩家可以自由地自行构建前进方向,那么游戏的难度就可以让大家满意。

重议刷任务

在《Defender’s Quest》中,我们将玩家驱动目标与刷任务结合起来,我们觉得这种方式能够尽量扩展用户数量,并且不会降低核心游戏可玩性或浪费任何人的时间。

让我们先来看看以下屏幕截图:

该游戏与《最终幻想策略版》等策略RPG和诸如《超级大战争》等其他战术游戏一样,每场战斗都发生在大地图的单独地点上。我们的游戏主要注重的是战斗、自定义和故事。探索暂且放在次要位置。

在《Defender’s Quest》中完全没有随机战斗。每场战斗都设计独特,而且有从非常容易到非常困难等各种挑战难度。要进入下场战斗,玩家所要做的就是在战斗最容易的挑战中存活下来。

三种“主要”挑战模式是普通、高级和特级,用地图中每场战斗发生地下方的星星数量来表示。“普通”模式是自然的起点,“高级”和“特级”中会遇到更高难度的挑战,玩家应该在获得些许经验之后再回来玩这两个难度。

这种设计让玩家可以自行设定目标,而且使得刷任务也不会那么乏味。如果玩家只是为了打通游戏,他们可以完全忽视更高难度的挑战。但是,如果他们真得喜欢游戏,也不用浪费时间一遍遍地玩相同的战斗。反之,他们可以尝试之前关卡中较高难度的挑战。

而且,这些不同的挑战模式都与关卡的基本设计有所不同。这可以让追求成就感的人通玩所有难度,获得100%的完成度,而且还可以保证技艺不精的玩家可以在游戏中流畅地进行下去。

但是,即便游戏中有这些挑战模式,我们发现某些玩家仍然需要游戏难度降到基准线以下。这让我们左右为难,因为我们不希望许多高级玩家因为误选最容易的挑战并且认为这是我们设定的起点而离开游戏。

为解决这个问题,我们增加了新的模式,设置显示更小的星星,将新挑战模式命名为“休闲”。而且,还在游戏中设置了工具贴士明确地阐述各挑战间的差异。

我们并没有在每场战斗下面的星星调整为4个,而是设置成打通休闲模式后亮起半颗星,这样玩家仍然可以很直观地察觉到“普通”模式是基础难度和预设的起点。效果如下图所示:

休闲模式让许多测试玩家感到惊奇。它不仅扩展了难度空间,也让游戏满足更多非目标玩家的诉求。许多测试者提到,因为自己已经成年,所以玩游戏的时间会很少,尤其是那些需要耗费60多个小时的RPG游戏。休闲模式不仅为那些认为普通模式难度过高的玩家提供了解决方案,而且还受到了那些时间不足的玩家的喜爱。现在,完成《Defender’s Quest》所需的时间为5到50个小时不等。玩家可以在休闲模式中取得急速的进展(游戏邦注:这对那些只关注故事的RPG粉丝是个理想的选项),也可以尝试在每次挑战中都做得很完美,从战斗和升级系统中体验战术安排带来的快感。

对于我们做出的最后一个选择,我觉得可能会引起争议:

不同难度,同种结局

打通关卡的休闲挑战获得通关分数是在游戏中取得进展和看到过场动画的唯一必要条件。而且,游戏有着不同的结局。无论你打通的是哪个挑战,游戏的所有结局都可以实现。以下这个故事可能会让你明白我想说什么。

某些游戏因其难度而产生吸引力。征服某个有着极大难度的游戏带来的奖励确实很甜美,尤其是当这个奖励是美好的结局时。比如,我永远不会忘却首次打通《Cave Story》中“地狱级”挑战并解锁最佳结局(游戏邦注:挽救了游戏中某个玩家认为必死的角色)带来的那种胜利感。

这种挽救惨事产生的快感是好莱坞的电影所无法比拟的。这是我曾经在电子游戏中获得的最佳体验之一。

但是,作为一名设计师,我想知道有多少《Cave Story》的玩家获得与我相同的感觉。而且,游戏中的挑战已经快接近我的能力顶峰了,技能较差的玩家发挥其全部能力能够获得与我相同的挑战和成功感吗?

少部分玩家会找到其他方法看到他们无法打通的游戏的结局,这种情况是存在的。他们可能采取的方法包括作弊码、使用他人的存档等,让他们能够以某种应付得了的方式来玩游戏。如果要强迫这些人采用上述方式来享受电子游戏,那么作为游戏开发者的我们为何不采用折中方案满足他们的诉求,或者预先给他们提供合适且不会破坏游戏体验的工具呢?(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

RPGs, challenge, and grinding

Lars Doucet

As part of an ongoing series on our upcoming tactical RPG Defender’s Quest, I’d like to talk about RPG’s, challenge, and “grinding.” Let’s start with accessibility.

Accessibility

Accessibility is about expanding your game’s audience by removing barriers.

The word “accessibility” immediately brings disabilities to mind, and as I’m disabled myself, let’s start there. Many games require good vision, hearing, reflexes, as well as two hands and ten fingers. Often, these physical requirements are arbitrary, and the game could easily be redesigned so that a person with poor vision, no hearing, slow reflexes, and only one hand could still play the game to completion. These accommodations are rarely difficult or expensive to implement, and include such simple features as customizable controls, variable game speed, and visual choices tailored to the color-blind.

Of course, you can’t accommodate everything. It’s tough to make visually intense games accessible to the totally blind, for instance, just as it’s tough to make mountains accessible to quadriplegics. I’m talking about printing books in braille here, not installing chair lifts to the top of Mt. Everest.

But the disabled aren’t the only people who are often turned away from games, and physical skills are simply one barrier among many. Plenty of non-disabled players are turned away in droves from games they could have otherwise enjoyed, usually by the game’s difficulty.

Difficulty

Difficulty is probably among the top three reasons why people never finish a game. Just as removing assumptions about physical skills expands the game’s audience to the disabled, removing difficulty expands the game’s audience to less hard-core players. But how can a game remove difficulty without under-mining the experience?

A perfect example of an incredibly difficult and hard-core game that expands its audience through accessibility is VVVVVV.

The accessibility options allow you to slow the game down, turn visual effects on and off, and even make yourself invincible. These options help expand the game to both disabled and casual players alike. It’s quite surprising to see such features in such a hard-core game, especially given how many developers like to brag about how hard their games are (Demon’s Souls, anyone?).

As my disabilities (Narcolepsy and Tourette’s Syndrome) don’t affect my ability to play games, I just kept the normal settings. For me, slowing the game down or making myself invincible would “ruin” the experience. So you know what? I didn’t turn them on.

I played the game and had a blast. Furthermore, the game has extra difficulty modes and challenges for those who somehow find it too easy. These are normally unlocked through play, but you can unlock them yourself from the main menu if you want. Personally, I like the feeling of achievement that comes with unlocking things myself – so you know what I did? I didn’t unlock them from the menu.

Meanwhile, I’m sure some gamer who hates being forced to unlock content they already paid for got to enjoy the bonus features immediately. Another controversy solved through choice – everybody wins, so long as “winning” isn’t defined as “forcing everyone to play the game the same way.”

Removing barriers for other players, and even adding special features just for them, in no ways affected my enjoyment of the game. Instead, I got exactly the experience I wanted, and so did plenty of other players. This took a game that started with a narrow, niche appeal, and expanded it as far as its core design would allow. I’ve heard some hard-core gamers argue in comment threads that any extra effort spent making a game accessible should have been spent “making the game better,” instead. Not only does this smack of entitlement, I fail to see how enabling diverse play styles doesn’t count as “making the game better.”

But more importantly, an interesting principle seems to be emerging here: Players naturally seek out a level of challenge that matches their abilities.

Corollaries:

If the game is too easy, players will try to make it more challenging.

If the game is too hard, players will try to make it easier.

I think games should be designed so that all the tools the player needs to make the game easier or harder are right at their fingertips, without forcing the player to resort to hacks, cheat codes, and custom mods just to get an experience that’s right for them. This should be done in a way that doesn’t insult the player or cheapen the experience they’re trying to set for themselves.

So, what does this have to do with RPG’s, grinding, and Defender’s Quest?

Grinding

Grinding is one of the oldest accessibility options in games. If the player can’t beat the next boss, she can always beat up some monsters, level-up, and try again. This allows players of widely different skill levels to complete the same game on their own terms.

Whereas elite Final Fantasy I players could beat the last boss at the recommended Level 35, noobs like my 8-year old self had to grind up to level 50 to stand a chance. It wasn’t a perfect solution, but it did offer a convenient “safety valve” that ensured that the game would not be impossible. Back when it was an uncommon experience to see the end screen of any video game, RPG’s were the only kind I could expect to finish.

At its best, grinding assures the player that victory is possible if they just keep playing.

At its worst, grinding artificially extend the game’s length, and exploits the player through Skinnerian principles and addiction mechanics (as in certain facebook games).

Grinding is simultaneously crude and elegant.

It is crude because it punishes weaker players, who must spend more time grinding, and who often have less time to spend in the first place. Furthermore, grinding itself is usually tedious.

It is elegant, however, because it lets the player smoothly adjust challenge just by playing the game, without any up-front commitments. Not only can a casual player lower the bar by grinding, a hard-core player can raise it by refusing to grind, like trying to beat the Final Fantasy I at level 25.

When done correctly, the game’s challenge becomes self-regulating. The player can naturally adjust the challenge level up or down as she progresses through the game.

Sam is a player that has weaker skills than the designers expected, below even what the game considers a “casual” level of play. Sam thus has to grind throughout the game to keep the challenge low. Sally grinds a little bit, keeping the game around the “normal” level of challenge, whereas Bob refuses to grind except for just once late in the game, raising the bar as high as possible.

Now, let’s see what happens to Sam’s experience if we remove the option to grind. Sam must now pick from “Easy,” “Normal,” and “Hard” difficulty modes at the start. Being a weak player, Sam opts for “Easy” mode, only to find that most of the experience is still too hard for him. Game designers often misjudge what counts as “easy,” so I will join with Ernest Adams’ in demanding that “Easy Mode is Supposed to be Easy, Damm it!”

The dark blue curve represents the level of challenge Sam would like to pursue, but without the ability to grind, he has no choice but to follow the difficulty curve dictated by the game’s so-called Easy mode. With no way to adjust this, Sam will probably quit soon after Dungeon 1.

Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment

A common solution to this problem (besides grinding) is “dynamic difficulty adjustment”, or DDA. In this method, the game adjusts the difficulty mid-game in response the player’s performance. One of the earliest examples of this is the arcade shooter Dragon Spirit. In this game, the first level was a hidden test – if you die, instead of losing a life you simply continue the rest of the game in “easy” mode, but if you survive, you continue in “normal” mode. This effect is largely invisible to the player.

Of course, when the player finds out they can feel cheated, and might respond by resetting the game whenever they die on the first level. Other approaches to DDA, such as in God of War and Devil May Cry, fix this problem by explicitly offering the player the choice of an easier difficulty mode after several deaths. This puts control back in the player’s hands, but sometimes feels like an insult.

DDA works, but it’s not perfect. The problem is that any pre-ordained difficulty mode can never match an individual’s unique challenge curve, and switching between difficulties mid-game often just means choosing between “too hard” and “too easy.”

Grinding doesn’t work for all genres, but I prefer it to DDA for RPG’s. Both methods lower the difficulty bar, but grinding at least makes me feel like I’ve done something. DDA just makes me feel like a loser who needs to go back to the bunny slope.

Player-Driven Goals

Another solution to the difficulty problem is to let the player set their own goals. Donkey Kong Country 2 is a great example, which I’ll leave to David Sirlin to explain. Summary: simply beating DKC2 is “fairly easy,” but finding all the secrets and going for 100% completion is difficult, and the player gets to decide for herself what she wants to achieve. In this way, DKC2 lets the player chart her own difficulty curve. When the game is “too easy,” she can go after more secrets to ratchet up the challenge, but when the game gets “too hard,” she can settle for just beating the level.

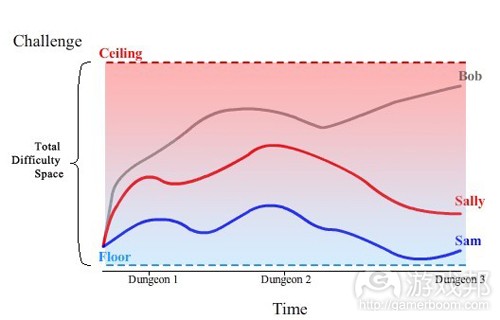

I’ll disagree with David on one minor point – simply beating DKC2 is not “fairly easy” – either that, or my wife and I totally suck at classic video games. Either way, my point is that so long as the player is free to chart his own path, you can’t go wrong by both lowering the floor and raising the ceiling on the game’s difficulty.

Back to the Grind

For Defender’s Quest, we combined player-driven goals with grinding in a way that we feels expands the game’s appeal to as wide an audience as possible, without watering down the core gameplay or wasting anyone’s time.

Let’s start with a screenshot:

In keeping with the conventions of tactical RPG’s such as Final Fantasy Tactics, and other tactical games like Advance Wars, each battle is a unique set-piece on a large map. This comes at the cost of foregoing a free-roaming overworld, but given our non-existent budget and disdain for random battles it felt like the right choice. Our game tightly focuses on battles, customization, and story. Exploration will have to wait for the sequel.

There are exactly zero random battles in Defender’s Quest. Each battle is uniquely designed, and comes with several challenge variations ranging from very easy to very difficult. To progress to the next battle, all the player has to do is survive a battle on the easiest challenge.

The three “main” challenge modes are normal, advanced, and extreme, which correspond to the three stars underneath each battle on the map. The different modes are balanced such that “normal” is the natural starting point, with “advanced” and “extreme” being extra challenges the player should come back for later when they’ve gained a little experience.

This lets the player set their own goals, as well as making grinding less boring. If the player just wants to play through the game, they can ignore the higher challenges. If they do get stuck, however, they don’t have to waste time playing the same battles over and over again – instead, they can try some of the harder challenges from earlier levels, which are now within their reach.

Furthermore, each of these different challenge modes features a unique variation on that level’s basic design. This lets achievers ratchet up the difficulty and go for 100% completion, while still allowing weaker players to progress without getting stuck or bored.

Even with these challenge modes, however, we found that some players still needed the ability to “drop down” to something easier than the baseline. This caused a bit of a dilemma, since we didn’t want more advanced players to get turned off if they accidentally picked the easiest challenge, mistaking it for the intended starting point.

To solve that, we added a vertical separator, made the star smaller, and gave the new challenge mode the name “casual,” as well as tool-tips to explicitly spell out the differences between challenges.

And, rather than adding a fourth star underneath each battle, we made beating casual mode simply fill the first star half-way, so that “normal” mode is still clearly the baseline and intended starting point:

Casual mode was a hit with many of our testers. It not only opened up the difficulty space, but also increased the game’s appeal to an unexpected audience. Many testers mentioned that since they’d grown up they have a lot less time to play games, especially 60+ hour epic RPG’s. Not only does casual mode offer a solution to getting stuck, it offers a solution to not having time. The upper and lower bounds for completing Defender’s Quest now sits at roughly 5-50 hours. Players can fly through in casual mode (ideal for the sub-set of RPG fans who are “just here for the story”), or they can squeeze every ounce of tactical goodness out of the battle and upgrade systems by trying to go for “perfect” on every single challenge.

We made one last choice, however, that I feel might be controversial:

Story is never held hostage by difficulty

Beating a level’s casual challenge with only a passing score is all that is necessary to progress and see the next cut-scene. Furthermore, the game has multiple endings, all of which are equally achievable no matter which challenges you beat. Let me relate a quick story so you can understand where I’m coming from on this one.

Certain games are appealing because they are difficult. The reward of conquering an insanely-hard game is all that much sweeter, especially if that reward is a better ending. For instance, I will never forget the feeling of triumph I had when I beat the “Running Hell” challenge in Cave Story for the first time, unlocking the best ending, which prevents the death of a beloved character I previously thought to be inevitable.

Conquering a tragedy by being totally freaking awesome adds punch to a happy ending in a way that schmaltzy Hollywood fare simply can’t match. It ranks among the best experiences I’ve ever had in a video game.

As a designer, however, I wonder how many Cave Story players ever made it that far. Furthermore, this particular challenge was right at the edge of my abilities. Wouldn’t a weaker player have felt the same sense of challenge and triumph if he could play right at the cusp of his skills? Would allowing him that triumph cheapen my victory, knowing that I could have lowered the bar for myself? And even if supposing it would cheapen my victory, why should the game’s designer pander to me rather than the other guy?

Inevitably, some small fraction of players will find ways to see the endings to games they can’t beat. Either they will use a cheat code, hack the game, or wait for tools like emulator save-states to arrive that let them play the game in a way they can handle. Rather than forcing these persistent few to jump through hoops simply to enjoy a video game, why don’t we as game developers meet them half-way, and just give them well-balanced tools up-front that don’t spoil the experience for anyone? (Source: Gamasutra)

下一篇:阐述建设性反馈信息的4大标准