合理利用图式理论可以提升游戏趣味性

作者:Soren Johnson

首先,请认真阅读以下这段话:

步骤很简单。首先,将这些东西分成不同的组合。当然,如果量很少的话,一堆就可以了。如果你需要去的那个地方设施不够便利,那么就可能要再多执行下一个步骤。如果不是,那就说明你已经准备好了。重点在于知道“过犹不及”这个道理。从短期来看,这样做似乎并不重要,但如果不注意就很容易引起麻烦。错误的做法可能让你付出昂贵的代价。首先,整个步骤就会显得很复杂,不久之后,生活可能就变了一番模样。

这段话是不是看起来毫无意义呢?原因在于这段文字没有上下文背景。现在,尝试带着“洗涤脏衣服”这个观点再次阅读这段话。

现在,以上信息读起来的感觉就完全不同了,这些内容有了真正的含义。这段文字是叫你如何洗衣服的指导信息。事实上,现在你已经知道了文字的背景,再要求你无视背景来阅读这段话几乎是不可能实现的了。

图式理论

这是图式理论的一种范例,解释我们的大脑如何对世界进行分类。从本质上来说,图式是围绕某个特定主题的心理框架,帮助我们处理和归类新信息。

比如,狗的图式信息包括它们的身体(游戏邦注:比如四条腿、有毛发、有尾巴)、它们的行为(游戏邦注:如吠叫、流口水、追逐猫)和它们的品种(游戏邦注:如牧羊犬、猎犬、贵宾犬)。而且,狗图式还包括更高层次图式的特征,如属于哺乳动物(游戏邦注:温血、脊椎动物、胎生)和适合作为宠物饲养(游戏邦注:喜欢家庭生活、忠诚、训练有素)。所以,当遇到狗时,我们的心理图式便会调用这些信息,让我们知道这种动物会有何种行为。

但是,图式只有激活后才能够发挥作用。之前提到的那段话毫无意义,直到“洗涤脏衣服”这个短语触发了读者心理中合适的图式。如果没有图式,文字本身毫无用处,这是那些想要有效与读者交流的作家需要重点考虑的事情。

游戏和图式

游戏设计师也需要有效地交流信息,也就是玩家必须学习和掌握的规则和机制。这种教导过程是游戏开发者面临的最大挑战之一,许多有着有趣系统的游戏最终失败,完全是因为只有少数玩家能够学会其中的机制。目前有许多工具可用来解决这个问题,包括节奏安排妥善的教程、能够起到作用的工具提示和可接入性良好的UI,但最为简单的方法可能是激活玩家大脑中与游戏基础机制相符的图式。

比如,桌游《Agricola》激活了玩家的农耕图式,来传授相对复杂的经济引擎。玩家已经理解了犁地、播种、收获小麦、烘焙面包和供养家庭这个顺序,这使得资源、土地、升级和动作间的复杂互动更容易学会。因而,游戏主题的最重要的工作之一是帮助玩家理解并记住游戏机制,这也是为何游戏主题和机制应该相配套的原因所在。

《Coloretto》和《Zooloretto》这两款互有联系的桌游也能说明图式的强大力量。这两款游戏使用相同的而游戏机制,惩罚获得过多不同类型道具的行为。比如,玩家在《Coloretto》收集7套不同颜色的卡片,但是只有最大的三套能够获得分数,其他颜色的卡片都只能扣除分数。

同样的机制也在《Zooloretto》中出现,玩家需要集中的是同样种类的动物而不是同种颜色的动物。游戏主题的这种设置能够激活玩家的动物园图式,以此来判定得分系统的做法。《Coloretto》新玩家需要得到明确指示才能知道超过3种颜色的卡片会带来副作用,而《Zooloretto》新玩家可以直观地从游戏中意识到,他们所拥有的牢笼有限,收集其余的动物是毫无用处的行为。玩家大脑中的动物园图式让他们明白不同种类的动物应当关在不同的地方,这使得游戏更容易学会。

而且,某些主题相对比较容易激活玩家的图式。历史或当代主题相比科幻或玄幻主题而言更能为用户所接受。相对比《星际争霸》中的mutalisk和dark templar而言,玩家更容易猜到《帝国时代》中骑士和弓箭手的作用。事实上,多数玄幻题材游戏都会采用精灵和矮人等玩家所熟悉的内容。诸如《可汗》系列(游戏邦注:采用波斯神话来塑造玄幻世界)等采取别样做法的游戏通常都不会特别出众,因为玩家无法使用他们因《魔戒》而形成的图式。

现实性与趣味性

使用图式作为工具来让玩家触及游戏系统会产生现实性的问题,因为规则需要精确地符合玩家在心目中的假想情况。如果棒球游戏中的规则与现实规则不同,不但会使得玩家的棒球图式无法发挥作用,还会让玩家市场感到糊涂。

因而,设计师必须考虑现实性,这也是重要的工具。但是,游戏开发者们似乎对现实性并无好感。比如,有些粉丝会专门盯着挑游戏中犯下的历史细节错误。确实,Sid Meier曾经说过:“当趣味性和现实性发生冲突的时候,首先应该顾及趣味性。”

但是,这是个错误的选择。现实性能够让玩家更容易学习游戏机制,这会让游戏显得更好玩。过于追求游戏现实性的危险在于,有些设计师希望游戏需要玩家将大量的知识带到游戏中,这可能会限制游戏的潜在用户数。比如,某款二战游戏设置不同的德国装甲车有不同的性能,这是可取的做法,但是如果游戏希望玩家自己去掌握各种装甲车的优劣而不提供游戏内的指导,这就是个问题了。

而且,认知真实比实际上的真实更加重要。最重要的问题是,如何在开始游戏之前预构建玩家的图式。如果某种错误的想法已经为大多数人所接受,那么最好根据他们的想法来制作游戏(游戏邦注:出于教育目标的游戏除外)。

比如,Sid Meier并没有完全根据历史记载来构建《Pirates!》这款游戏,主要根据却是海盗电影,也就是好莱坞式的海盗时代。所以,每个海盗都有个长久被西班牙人扣押的妹妹,每个小酒馆中都有个神秘的陌生人拿着藏宝图的关键部分。同样,Will Wright也没有真正基于家庭生活来开发《模拟人生》,而采用了情景喜剧的风格。

题材图式

图式并不需要完全与游戏世界分离。游戏资深人士最终会开发出他们自己的图式,而这些是设计师必须遵循的。更为准确的说,玩家会根据游戏题材而产生相关图式,比如第一人称射击图式、平台游戏图式、战斗游戏图式等。

就像玩家遇到新狗会期望它做出某些符合脑中的狗图式的行为一样,那些遇到新即时战略游戏的玩家也会希望游戏符合心中的RTS游戏图式。玩家可能希望游戏能够设置成俯视,可以控制多个单位,需要矿工开采资源获得金钱,有军事和科技的基本建筑,更高层次的游戏平衡等。

避开这些特征的游戏可能会显得很特别,但几乎无法取得商业上的成功。用户在花60美元购买新游戏时会显得很保守,他们在购买之前对游戏的理解越深刻(游戏邦注:即游戏符合题材图式),他们会越愿意购买游戏。所以,题材图式对行业内的创新会产生很大的影响。

可能解决题材图式限制性的最佳方法是,通过游戏的真实主题向玩家提供非同寻常却更强大的图式。比如,《Nintendogs》并没有完全符合某种成功的商业题材,但是游戏中照顾宠物狗的主题激活了用户的图式,因而这款游戏得以畅销。这款游戏之所以能够吸引玩家,这得益于他们已经对宠物狗很了解。

产生意义

确实存在部分愿意涉足自己不熟悉题材的玩家,比如《Dwarf Fortress》和《Dominions》系列游戏早期的玩家。但是,多数玩家只有在理解游戏主题之后才会选择游戏。因而,设计师需要用图式来吸引玩家,可以通过游戏的可视化主题,也可以利用某些已经为人所熟知的题材传统方法。

但是,虽然后者可以成功地将游戏销售给忠实的核心玩家,但只有前者才能让游戏接触主流受众。当然,任天堂Wii是这个主机时代中最棒的例证。除了控制系统的可接入性之外,该公司旗下许多畅销游戏都有着鲜明的主题,能够轻易激活用户的图式。那些有关太空飞船和巫术的游戏就没有这种优势。

然而,找到能引起用户反响的主题只是成功的一半,游戏的机制也必须与主题相符。老式的“趣味性超越现实性”的看法会让设计师处于趣味性的需求而打破游戏主题与其机制的联系。玩家开启新游戏时总是带有愿景,所以玩家有权期待游戏能够符合自己的图式。

游戏邦注:本文发稿于2011年2月4日,所涉时间、事件和数据均以此为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Game Developer Column 15: Start Making Sense

Soren Johnson

First, read the following paragraph carefully.

“The procedure is actually quite simple. First, you arrange things into different groups. Of course, one pile may be sufficient depending on how much there is to do. If you have to go somewhere else due to lack of facilities, then that is the next step. Otherwise, you are pretty well set. It is important not to overdo things; that is, it is better to do too few things at once than too many. In the short run, this may not seem important, but complications can easily arise. A mistake can be expensive as well. At first, the whole procedure will seem complicated. Soon, however, it will just become another facet of life.”

Did the paragraph make any sense, or did it seem like a string of nonsense? Most likely, it was the latter, and the reason is that the text is completely devoid of context. Now, try reading the paragraph again, but think of this simple phrase first: “dirty laundry.”

Now, the information should read completely different and actually mean something. The text is simply a set of instruction about how to wash one’s laundry. In fact, now that context has been established, reading the paragraph again without thinking about clothes is probably impossible.

Schema Theory

This transformation is an example of schema theory, which tries to explain how our brains categorizes the world. Essentially, a schema is a mental framework centering on a specific theme, helping us process and classify new information.

For example, a schema for dogs include information about their bodies (four legs, hair, tail), their behavior (barking, drooling, cat chasing), and even their breeds (collies, spaniels, poodles). Further, the dog schema can contain traits from higher-level schemas, such as for mammals (warm-blooded, vertebrates, live births) and pets (domesticated, loyal, house-trained). Thus, when encountering a dog, our pre-existing schema brings with it a wealth of information that informs us on what to expect from the animal.

However, schemas are only useful if they are activated. The original paragraph was meaningless until the appropriate schema was triggered in the reader’s mind by the simple phrase “dirty laundry.” The text itself is useless without the schema, which is an important consideration for an author who wants to communicate effectively.

Games and Schemas

Game designers also need to communicate something effectively – a set of rules and mechanics that the player must learn and master. This education process is one of the biggest challenges game developers face, and many games with fun systems have failed simply because few players get past the learning curve. Many tools exist for solving this problem – well-paced tutorials, helpful tooltips, accessible UI – but perhaps the simplest approach is to activate one of the player’s pre-existing schemas that is well matched with the game’s underlying mechanics.

For example, the board game Agricola activates the player’s farming schema to teach a fairly complex economic engine. Players already understand the order of plowing a field, planting seeds, harvesting wheat, baking bread, and feeding one’s family, which makes the complex interactions between the resources, fields, improvements, and actions easier to learn. Thus, one of the most important jobs of a game’s theme is to help the player understand and remember the mechanics, which is another reason why a game’s theme and mechanics should be well matched.

Another good example of the power of schemas comes from the related board games Coloretto and Zooloretto. Both games use the same underlying game mechanic of set collection with penalties for acquiring too many different types of items. For example, in Coloretto players gather cards of seven different colors, but only the player’s three largest sets score positively; all other color sets score negatively.

The same mechanic is at play with Zooloretto but with herding animals of the same species into pens instead of gathering identical colors. This difference gives the game a strong theme that activates the player’s zoo schema, which actually justifies the scoring system. New Coloretto players need to be told explicitly that every color past their third will hurt them while new Zooloretto players can see clearly from the board that they only have so many pens available – extra animals will remain useless in the barn. The zoo schema matters because the players’ pre-existing knowledge about zoos – that animals of different species are placed into separate pens – makes the game easier to learn.

Furthermore, some themes will activate a player’s schemas easier than others. In particular, historical or contemporary themes have more resonant schemas than sci-fi or fantasy themes. Players can more easily guess how Age of Empire’s knights and archers function than how StarCraft’s mutalisks or dark templars do. Indeed, most fantasy-based games tend to follow very well-established tropes (elves, goblins, dwarves) with which the player is already familiar. Those games which color outside the lines – such as the Kohan series which based its fantasy world on Persian mythology – often fall flat because players cannot use their pre-existing Tolkein schema.

Realism vs. Fun

Using schemas as a tool to give players a window into a game system raises the question of realism because the rules also need to accurately mirror the assumptions the players bring with them. If a baseball game gave the player four outs instead of three, the use of the baseball schema would not just be useless but actually counter-productive because players would be constantly mixing up the exact rules.

Thus, realism matters and is an important tool for designers. However, realism has earned a bad name among game developers. For instance, fans who nitpick over small historical details that a game gets wrong are called “rivet counters.” Indeed, Sid Meier famously said that “when fun and realism clash, fun wins.”

However, in many ways, this choice is a false one. Realism that gives the player an easier learning curve makes a game more fun, not less. The danger from an over-zealous pursuit of realism comes when the designer expects the player to bring significant outside knowledge to the game, limiting the potential audience. If a WWII game contains realistic ratings for different flavors of German panzers, that’s fine, but if the game expects the player to already know these ratings by heart, without in-game help, that’s a problem.

Further, perceived reality is more important than actual reality. The most important question is how the player’s schema is pre-built before starting the game. If a common misperception is widespread enough, better to support the players’ expectations than to subvert them (unless, of course, the design itself has an educational goal).

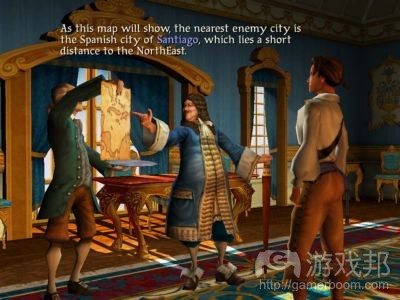

For example, Sid Meier primarily based Pirates! not on exhaustive historical records, but on pirates movies, Hollywood’s version of the era. Therefore, every pirate has a long-lost sister held captive by an evil Spaniard, and each tavern holds a mysterious stranger who might have a key piece of a treasure map. Similarly, Will Wright based The Sims not on actual domestic life but on a stylized sit-com version of it.

Genre Schemas

Schemas do not need to exist entirely separate from the world of games itself. Gaming veterans will eventually develop their own schemas for which designers must accommodate. More specifically, players will develop schemas related to how a genre is “supposed” to work – a schema for first-person shooters, for platformers, for fighting games, and even for rogue-likes.

Just as people who encounters a new dog expect certain behaviors based on their dog schemas, players who pick up new real-time strategy game come with their own sizable RTS schemas into which they expect the game to fit. The players might expect a God-level view, control of mutliple units, a peon-based economy, base-building for military and technology, a high-level boom/turtle/rush game balance, and so on.

Game which eschew too many of these features can hopefully become critical darlings (Majesty, Sacrifice, Dragonshard) but almost never achieve commercial success. Consumers are generally conservative when dropping $60 on a new game, and the better they can understand a game before purchasing it – often by fitting it squarely into the framework of a genre schema – the more comfortable they will feel. Thus, genre schemas have a significant chilling effect on innovation within the industry.

Perhaps the best way to overcome the limitations of genre schemas is by providing the consumer a different yet stronger schema via the game’s actual theme. For example, Nintendogs did not fit well into a successful commercial genre but the game’s theme – taking care of a pet dog – activated the schemas of consumers with so many clear possibilities that the title became one of the best-selling games of all time. The game sold itself to players primarily on the basis of what they already knew about dogs.

Making Sense

A certain breed of player does exist that is unafraid to dive into unfamiliar territory, such as the early adopters of iconoclastic cult games like Dwarf Fortress and the Dominions series. Most players, however, need to understand what a game is about before they even touch a controller. A schema hook is required, either via the game’s visible theme or some well-established genre conventions.

However, while the latter can successfully sell a gaming to faithful core gamers, only the former can expand gaming to a mainstream audience. Certainly, the Nintendo Wii was the greatest example of this fact during the current console generation. Besides the accessibility of the controls, many of the best-selling games – such as Wii Fit, Mario & Sonic at the Olympic Games, Just Dance, and – yes – even the oft-derided Carnival Games – all have very clear themes that easily activate consumers’ schemas and expectations. Games about space marines and evil wizards do not have this advantage.

Still, finding a resonant theme is only half the battle; a game’s mechanics must match the theme as well. The old “fun beats realism” saw has become such dogma that designers can easily fray the connections between a game’s theme and its mechanics in the very subjective pursuit of fun. Starting a new game is always a leap of faith, and players have a right to expect their games to start making sense. (Source: DESIGNER NOTES)

上一篇:游戏设计师不可盲从所有用户的需求

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号