Mobile Pie分享《B-Boy Brawl》迭代开发经验

作者:Will Luton

介绍

在这篇文章中,我将讨论一种可在小型独特项目中反复使用的游戏创造方法,并描述我们的工作室Mobile Pie在使用这种方法设计iPhone和iPod touch游戏《B-Boy Brawl: Breakin’ Fingers》过程中遇到的成功与失败。

我会讨论我们最初基于传统线性电子游戏设计的方法及其演变过程,失败让我们看清了遇到的问题,知道如何制造出有趣且功能齐全的核心游戏机制,并将这个过程成功应用于其他游戏的开发中。

在讨论电子游戏设计时,我将用上Ian Bogost的单元操作理论,这个理论指出,电子游戏由营造表达某种意图的整体系统的单元操作构建而成。我们可以做出如下假设,我们用于构建完整系统或电子游戏的方法必须以彻底理解这些单元操作如何互相产生作用以实现预想结果为前提。

当然,将现有系统解构并重新构建较为容易也更为便捷。然而,如果我们想要构建与现有系统不尽相同的全新系统,那么我们就必须选择能够相互配合营造预想目标的正确的单元操作(游戏邦注:以及设计元素),但是这些选择有一定的技巧并且有时并不符合逻辑性。

我建议,开发者必须通过重复性开发过程来创造、测试和润色独特的系统,观察系统的反馈,分离那些有碍于预想目标的元素,将它们替代成那些更为适合的元素,重复这个过程直到实现令人满意的结局。

以上推荐的过程似乎已为许多老练的电子游戏设计从业者所熟知,尤其是那些经验丰富的Agile方法使用者。但是,本篇文章将着重通过总结我们自身项目中的成功和失败来得出每个阶段的最佳做法和不同项目间方法使用的差别。

迭代开发的背景

长久以来,数字化内容传播都被认为能够将行业从巨额经费和实体零售瓶颈中解救出来。尽管游戏概念和开发硬件限制可能阻碍到某些开发行为,但PC和苹果App Store二者都能够让小型开发团队自由开发商业化的独特游戏,涌现出类似于《Zen Bound》和《World of Goo》的有趣游戏体验以及成千上万个失败作品。

随着电子游戏生产成本增长并且收益逐渐减少,所有新游戏的开发都会面临更大的金融风险。为使游戏市场规范发展,发行商和工作室已经很少再为不知是否有效的设计元素开绿灯。开发者的关注点从设计的创新性转变为注重游戏收益,这种做法正逐渐侵蚀电子游戏体验并且会影响用户对游戏的信心。

巨额预算和微薄利润也带来了一种严格的微管理文化,主要体现在紧凑的项目开发日程安排,以及对“计划性设计”方式的高度依赖,它将市场营销意图和风险规避设计手法融为一体,使游戏创意性与商业性合二为一。

虽然大型游戏发行公司可能更喜欢采取上述方式,小型独立开发商却因发布某些吸引眼球但与商业化游戏差异过大的游戏而损失惨重。

这些失败部分归咎于开发方法,业界过于信赖大型工作室的产品开发思想体系。依我在Mobile Pie的经验来看,将优秀的游戏想法在设计初期便交由小型团队负责会让他们处于危险的境地,因为时间安排会让游戏的质量大打折扣。

迭代设计开发的演变:《B-Boy Brawl》的成功和失败

迭代设计开发方法起源于创造《B-Boy Brawl: Breaking Fingers》的设计过程。

《B-Boy Brawl》的灵感来源于一系列YouTube上的视频,视频中的人们把手指当做手臂和腿,在一块小区域再现霹雳舞般的动作。视频最初的目标在于教人们如何重现动作,但是当我们讨论起这个概念时,我们形成了一个目标,并催生出了一款游戏。

通过这些早期的讨论,我们决定游戏要保持某些非常独特的设计想法:

1、传授移动方式。用户可以用来学习并记住每个独特的移动方式。

2、炫丽的游戏玩法。游戏让非游戏玩家看起来很有趣。

3、易用性。用户可以简单地学会游戏,无需过多的指导。

4、可适应性。允许用户自由地以不同的方法来做出相同的移动。

这些想法并没有记录下来,但是已经成为游戏项目不可改变的必要元素。我们在执行项目的开发中,这些想法限制了游戏的设计,但我们在无意间修改了设计以及开发手段。

在开发过程中,我发现这些想法中某些内容与其他想法有直接的冲突。从表面上来看,我们或许会发现易用性正与用户需要学习移动方式之间有所冲突。而且,以上两个想法和可适应性有着更深层次的冲突。某个相对合适的机制似乎能提高游戏的易用性,但在测试中我们发现与之相左的方法反而更好。

最早我规划了两个游戏原型的概念:其一以按键来显示用户手指应该放置的位置并以逐渐减少的圆圈来显示时间;其二用HUD来显示节拍以及当前、过去和即将到来的移动。

在这两个原型的基础上,我们猜想用户会如何同这两种方式互动。我们考虑到在游戏中添加按键的方法会让游戏显得约定俗成且单调,这会破坏炫丽游戏玩法和可适应性这两个想法。

但是,更为重要的是我们没有考虑以下问题:在向用户传播所需信息方面,这两种方法的有效性如何以及用户将会如何解读这些信息。我们只顾着考虑用户想要的东西,而忽视了用户可以使用的东西。

我们通过讨论和文件撰写来修改设计想法,最终构建了游戏的最初原型,现有的两个条状物方向不同,一个显示的是节拍,另一个显示移动。玩过游戏原型之后,开发团队对他们的劳动成果感到非常高兴。游戏像我们预想和计划的那样发展,当时我们能够断言,尽管游戏还略显粗糙,但是人们会喜欢这款游戏。

我们马上将原型提交给我们的同行,以听取他们的意见。我们知道游戏并不完美,但是肯定不会很差。看到游戏测试结果,我们感到很震惊。在这个阶段,有些人能够理解游戏机制并乐在其中,但有些用户甚至都不能明白游戏基本架构,两类用户的反应差距悬殊。

公司团队负责设计和执行整个系统,因而能够理解游戏的各项功能和机制、信息呈现的方式和形式、所呈现信息的内容,以及如何理解信息以做出正确的动作并获得丰富的体验。

我们从测试用户处获得各种反馈,有些用户的意见还会有一定的冲突。有些人对游戏大加抱怨,因为他们无法理解游戏玩法。还有些人声称,应该制定教程,音乐拍子应该慢些,失败的条件应该更宽松些,而且他们不知道下一步要把手指放在何处,拍子应该显得更为形象化。

我们收集众人的反馈,包括他们口头阐述的反馈和我们从他们的游戏过程中观察到的内容。我们构建起全新的原型,再次将上述想法融入其中,让新用户来体验并收集更多的可用反馈,不断重复这个过程直到我们拥有精致的原型。完成这个过程后,多数用户都能够在教程的辅助下明白游戏机制。

现在回想起来,这个成功也预示着更大的失败,在这些设计润色的过程中,我们通过削弱某些内容来提高游戏的可用性。随后,又有针对屏幕图像的反馈意见,声称这会让用户感到眼花缭乱。我们没有让游戏变得更具易用性,反倒使它变得更为复杂。

我们将游戏提供给发行商或其他愿意与我们合作解决营销和认证问题的人,我们发现在此等情况下游戏完全不具有易用性,我们创造出了个复杂的系统,只有通过超长的教程才能够解释清楚。

意识到这个问题后,我们召开会议讨论项目未来的发展。在一个小时的时间里,我们就发现了问题的根源所在并制定出了解决方案。我们曲解了测试用户的反馈,解决的只是游戏所存在问题的表象而不是原因。用户想要的东西(游戏邦注:即某些细微的改变)和他们真正需要的东西(游戏邦注:更容易理解的核心机制)是完全不同的东西。

解决方案很简单,即重新根据基于按键的原型来构建游戏,摒弃我们自己强加在游戏上的设计限制,也就是那些设计想法。

按键系统通过已经确立的按键图解来向玩家传达所需的动作,即按动或触摸。同时,利用封闭式的圆圈来显示时间。这些元素是让电子游戏和用户间产生预想互动的关键元素。

现在,用户已经不需要学习他们在游戏中用到的移动,核心机制让玩家跟随游戏节奏即可。这种做法弱化了游戏体验对旁观者的影响,却大大提升了产品的易用性和用户获得的游戏趣味性。

我们使用新引擎从头开始创建全新的原型,尽量避免之前犯下的错误。现在,我们不将想法强加在产品之上,而是构建、测试、解释上述解决方案,不断测试和重新构建,根据用户的反馈来进行游戏设计。

通过测试找到问题所在后,我们提出了一个解决方案并使用问题追踪软件进行记录。随后,我们将这种方法用于新的架构中,并对其进行测试。

在原型开发过程中,这个方案不断演变并且变得更为精致,随后便用来构建和改善内容,产生极具趣味性且易用性良好的产品。

对这些过程的理解使我细致分析了开发过程的行为,将它们进行分解并组织成设计方法,使得其他人也可以将优秀的想法在有限的预算和时间框架内转别成优良的游戏体验。

迭代设计开发方法的成型

这是种有着更为完整、精致并包容所有过程的框架,来源于Mobile Pie成员的经验和工作方法,并结合了Agile方法论。但是,不可将其视为电子游戏设计的权威方法。

这种设计很大程度上由产品本身推动,而不是使产品受到限制。因而,设计师的目标会更为明确。这种独特的效果使得这种方法适宜小团队,如精品独立工作室或学生团队,在毫无外界压力的情况下,他们可以在短期内制造出产品。

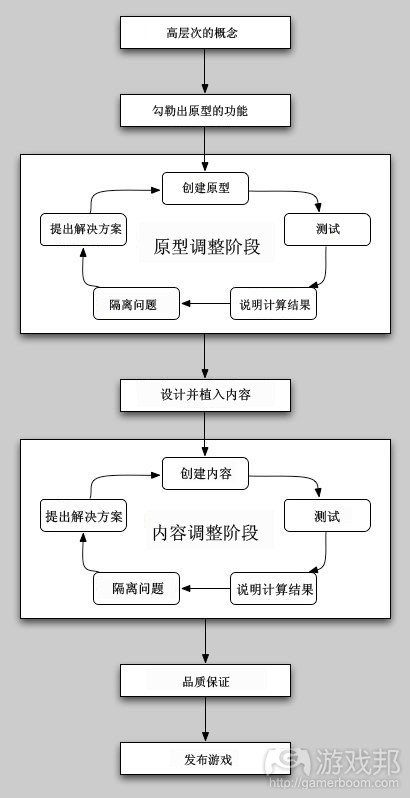

下图显示迭代设计开发的各个阶段的流程。

该过程起始是独特的高层次概念,随后团队成员进行讨论,罗列出原型中的功能。然后团队密切配合制作出最初的原型,最好能够使用游戏目标平台上的目标技术。

我建议不必过于拘泥于开发文件,团队成员间的口头交流能够更迅速地构建起原型,当然,这取决于团队成员的投入程度、可信度和民主作风。

一旦最初的原型确立,迭代设计过程就可以进入“原型调整阶段”。该阶段的每个循环都可以视为类似SCRUM Sprint的方法。

该阶段的测试过程和反馈的提炼是创造有效迭代的关键。你可以选择将玩家分组测试产品,也可以选择将游戏提供给同龄人或其他你偶遇的人进行测试。

重点在于,脑中不要有明确的精致度量,你应该观察用户及其行为以及他们所说的话。这是因为度量会让你对系统的功能问题产生预设的想法,但依我的经验来看,你作为系统的构建者,根本不可能预测到系统中的哪些元素会产生阻碍作用。

对测试中所得反馈的理解是种很高深的技能,其内容足以再写一篇文章来阐述。但是从常识上来看,倾听的能力以及对电子游戏功能的理解是非常宝贵的技能。

一旦整个团队同意原型能够发挥其功能时,就必须考虑设计和添加额外的内容了。这个阶段时间的长短和复杂性取决于项目的类别。

内容设计并执行之后,便进入了“内容调整阶段”。根据项目类型的差异,这个阶段与“原型调整阶段”相比时间可能较长也可能较短,但是所使用的原则与上述相同,即考察内容在核心机制下的功能如何。除非确为必要之举,否则不要对游戏玩法做过多的改变。

这个阶段过后,产品就处于可供测试的状态,应该进行QA来修补漏洞,随后就可以发布了。

迭代设计过程中的项目管理

这个方法可用于开发高质量游戏,但是由于其独特的效能,如果能够对项目进行恰当的管理,开发时间和成本都可以得到控制。

使用这种方法的风险在于,每个调整阶段所需的时间不确定。调整阶段的每个循环所耗费的时长并不确定,而且迭代的次数也没有限定。

但是,为对产品开发的时间和成本进行控制,就必须在项目开始前商定循环的次数和时间。

但是,包括内容开发等其他阶段都可以使用传统的模式进行控制。通过严格设定每个迭代阶段的时间框架,项目主管可以牢牢把控项目的整体开发时间和成本。

迭代开发过程的适用范围和适用性

尽管这种方法的目标用户是开发独特电子游戏的小型团队,但也可以用来提升大型主流电子游戏的体验的质量。在较为大型的项目中,重点可能会有所改变,可能应该更加关注内容。

这种方法还可以被小型团队用来创造大型项目游戏概念的样本,他们可以从内容迭代阶段的测试中获得反馈,改善未来内容的设计。

这种方法也可能用来改善多种产品的质量,但是需要根据团队的类型和预想的结果进行些许改变。

结论

迭代设计开发可以让小型但富有天赋的团队找到正确的方法,以开发出独特且富有创意的产品。

在开发循环中,它有着相对较大的自由度和灵活性。它还鼓励团队成员间在项目开始之处便开展合作,这意味着团队成为整体,而不是成员独立完成各个人物。

这个过程在Mobile Pie开发大量产品的过程中得到调整,还包含了学术性的设计理论和Agile项目管理理论。

我希望这种方法能够对那些与我们情况相似的开发商有所帮助,他们可以调整并讨论游戏内容,使这种方法进一步演变成为更有效的游戏开发方法。

游戏邦注:本文发稿于2009年10月15日,所涉时间、事件和数据均以此为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Making Better Games Through Iteration

Will Luton

Introduction

In this article I’ll discuss a game creation method through iteration for small, unique projects, and will describe how the failures and success of the process of designing our studio Mobile Pie’s upcoming iPhone and iPod touch title B-Boy Brawl: Breakin’ Fingers shaped that methodology.

I will discuss our initial design approach, based in the traditions of linear video game design, and how that evolved, through the failures we saw and the confusion we felt, to produce a core gameplay mechanic that is fun and functional and how the process can be refined and applied elsewhere successfully.

I will consider video game design according to Ian Bogost’s theory of Unit Operations; this suggests video games are constructed from discreet unit operations which function to create a system which delivers a desired meaning. We can hypothesize that our approach to building a complete system, or video game, must be based on a sound understanding of how these unit operations function with each other to achieve a desirable outcome.

Existing systems can be deconstructed and recreated verbatim or slightly deviated, with reasonable ease and security. However, if we wish to construct a new system, relatively unique from those that already exist, then we must choose the correct unit operations (or design elements, perhaps) which interact to create our desired outcome, however their selection is tricky and cannot always be deduced by pure logic.

Instead I suggest one must create, test and refine a unique system through an iterative developmental process; observing the feedback of the system, isolating the elements that pervert the intended meaning, replacing them with those deemed more suitable and repeating the process until a satisfactory result is observed.

The proposed process may seem self-evident to many seasoned video game design practitioners, especially those with experience of Agile methodologies, however, best practice at each stage and considerations for different projects are discussed throughout, with conclusions drawn from our own successes and failures.

The Context for Iterative Development

Digital content delivery has long been the prophesied savior for an industry creatively bound by huge overheads and a physical retail stranglehold. While concept approval and overzealous development hardware restrictions may hinder certain console outlets, the PC and Apple’s App Store both allow small development teams the freedom to test the water with commercial yet ambitious and unique games, providing for interesting experiences such as Zen Bound and World of Goo, as well as thousands of miserable, ugly failures.

As video game production costs grow and return becomes increasingly spread, ever more financial risk is put on all new development. In order to normalize the market, publishers, as well as studios, greenlight fewer products with unproven design elements; focus has shifted from design innovation to proven success and careful market positioning, slowly homogenizing the video game experience and potentially eroding consumer confidence.

The huge budgets and slimmer margins have also brought with it a culture of tight micro-management: both in terms of scheduling and over-reliance on meticulously pre-planned design, which incorporates the marketing will of licensing and small risk-free design deviations; both of these blights are linked creatively as well as commercially.

Although this may well be an understandable and, perhaps, forgivable norm for the large publicly held companies, small indie developers are gaining worldwide notoriety by releasing attention-grabbing games which deviate massively from the slew of cookie cutter commercial titles. However, for every Darwina or Alien Hominid there are a thousand nice ideas poorly realized that ultimately sink and disappear without even a ripple.

These failures could in part be blamed on development methodology; placing too much faith in the big studio ideology of immovable production paths. In taking a great idea and committing, what might seems sensibly, to the design very early on small teams can, from my experience here at Mobile Pie, put themselves in a perilous position where predetermined schedule is chased at the cost of quality.

The Evolution of Iterative Design Development: B-Boy Brawl’s Successes and Failures

The Iterative Design Development methodology was born from the evolution of the design process required to produce B-Boy Brawl: Breaking Fingers.

B-Boy Brawl was inspired by a series of YouTube videos in which people were using their fingers as arms and legs, to recreate break dance moves on a small scale. Initially the aim was to teach people how to reproduce the moves, but as we discussed the concept, goals were introduced and the product became a game.

Through these early discussions we decided the game was to uphold some very specific design ideals:

Teach the moves. For the user to learn and remember each unique move.

Theatrical gameplay. For the game to be fun for non-users to watch.

Accessible. For a user to easily pick up and begin playing, with little instruction.

Adaptable. Allow the user the freedom to perform the same move in different ways.

These ideals were undocumented, but existed as aims for the project and became immovable, fixed necessities. Although we approached the project with the idea of organic development these ideals restrained and shaped the design in an unexpected and unwanted way; we had inadvertently fixed design, and thus a development path.

Through development some of these ideals proved to be in direct conflict with one another in both obvious and obscure ways. On the surface we may see that accessibility is at conflict with the user having to learn moves. However, much deeper conflicts exist between both of these ideals and adaptability. A comparatively non-prescriptive mechanic may seem desirable to increase accessibility, but in fact the opposite was proven true, as during testing it became obvious users required more firm direction.

Initially, I documented two prototype concepts: one which featured buttons indicating where the user’s fingers should be placed, and decreasing circles to indicate timing, and another which featured a HUD displaying the beat and the present, past and upcoming moves.

Mocked shots of the two proposed prototypes, representing a button-orientated and a HUD-led design.

From simply looking at these prototype proposals, we made assumptions on how the user would interact with both. It was considered that having buttons would make the game too prescriptive and monotonous, destroying ideals of theatricality and adaptability.

More important, however, was what we did not consider: How effective each approach would be at serving the required information to the user and how they would interpret it. We were blinded by what we thought the user would want and so did not consider what the user could use.

We fixed the design through discussion and documentation and built an initial prototype of the game, where there existed two bars as the sole direction and feedback for the user: one indicating the beat, and one indicating the moves. Upon playing it the team was very happy with the results of their labor. The game played as we had envisioned and planned it, and we felt assured that, despite it being a little rough in its present state, people would enjoy it.

An early build of B-Boy Brawl running in landscape with the move and rhythm bar.

We immediately gave the prototype to our peers for review; we knew what we had was not perfect, but we certainly did not feel it was fundamentally flawed. Watching people play it — or fail to play it — came as a great shock. At this stage there existed an obvious disparity between the team playing it comfortably and enjoying it and the inability of our users to even grasp the basics.

The team had between us designed and implemented the entire system, and so had an intrinsic understanding of its functions; the way and form in which the information is presented, what the information represents, and how it should be interpreted to perform the correct actions and bring about an enjoyable experience. In linguistic terms, we were the ideal speaker-hearer, understanding without exception the meaning of the language — in this instance a video game interface — which we had created.

The feedback we received from our test audience was varied and occasionally conflicting; some blamed themselves for failing to understand the gameplay, others claimed tweaks should be made to the tutorial, that the music tempo should be slower, that failure conditions should be less stringent, that they didn’t know where to place their fingers next, or that the beat should be better visualized.

We took the feedback from the test subjects on board — both their verbal feedback, and that which we observed from their actions during play. We built a new prototype, still restrained within the ideals, had new users play it, collected more usability feedback, and repeated the process until we had a refined and much improved version of the initial prototype. At this point, with the help of the tutorial, almost all users were able to pick up and play it.

A refined version of the original prototype, still featuring the move and rhythm bars. Later these were merged in to one.

This success, in retrospect, also indicates a larger failure; over the course of these design refinements, we had partially achieved the ideal of usability through minor adjustments at the expense of some of our other ideals. The screen had become cluttered as new feedback elements crept in, confusing the eyes of the user. Rather than making the game more accessible, we had in fact made it more complex.

We took the game around to publishers and others who we wanted to partner with us to assist with marketing and licensing and found that in less controlled conditions that the game was, rather embarrassingly, not at all accessible; we had created an esoteric system which could only be understood through a lengthy tutorial.

After this realization, we called a meeting to discuss the future of the project and within an hour we had identified the root cause of the problem and produced a solution. We had been incorrectly interpreting the feedback from our tests and addressing the symptoms of a problem rather than the cause. What the users were asking for (the minor changes) and what they really needed (a more prescriptive core mechanic) were very different things.

The solution was irritatingly simple: to rebuild the game as the alternative button-based prototype, and disregard our self-imposed design restrictions — i.e. the design ideals.

The button system dictates the required actions to the player through the established iconography of the button — something to press or to touch. Meanwhile, the closing circle suggests timing. These elements were the key to producing the desired interactions between the video game and the user.

Now, the user was not required to learn each move they were expected to use; instead the core mechanics allowed the user to simply follow along. This, in turn, slightly reduced the theatricality of the experience, but greatly increased the accessibility of the product and the enjoyment users experienced.

We started the development of the new prototype from the ground up in a new engine, and took on board our previous mistakes. We now did not impose our ideals on the product, but instead built, tested, interpreted, proposed solutions, rebuilt and retested, with both the prescriptive and implied feedback of the user always leading the design.

After identifying an issue through test interoperation, a solution was proposed and recorded using a issue tracking software. This was then integrated in to the next build, and again the new build was tested.

The final revision of the B-Boy Brawl button-orientated design. Features a score, a multiplier bar and flashy particle effects.

This process evolved and became more refined over the course of the prototype development and was later utilized to shape and improve content, leading to a product which is enjoyable and intuitive.

The understanding of these processes has led me to consider our actions, break them down and formalize a design methodology to allow others to translate good ideas in to great experiences within limited budgets and timeframes.

A Formalization of the Iterative Design Development Methodology

This methodology is offered as a framework for a more complete, refined and inclusive process and is created using the collective experience and work ideologies of the members of Mobile Pie, as well as generalizations of Agile methodologies. It is not to be considered as a definitive approach to video game design.

This design approach is driven very much by the product itself, as opposed to a strict envisioning of the product; therefore the role of the designer becomes quite concrete. This unique fact makes it perfect for small teams of multidiscipline staff, such as boutique independent studios or student teams, working without external pressure, in short timeframes, to realize products.

The below diagram shows the phases of Iterative Design Development.

The various phases of Iterative Design Development.

The process begins with a unique high-level concept which is then discussed between the team members with the intention of outlining the functionality of a prototype. The team then works in close proximity to realize the initial prototype, ideally on the target platform with the target technology.

It is recommended that documentation is kept to a minimum and instead the prototype is built very rapidly by verbal communication between the team, with an even split of creative and technical skill sets having input. Of course, this relies on the team members being committed, reliable and democratic.

Once the initial prototype is created, then the iterative design process may begin with the Prototype Refinement Phase; each cycle of this process can be considered in a similar manner as a SCRUM Sprint, where the Product Backlog taken in to a Sprint is, in this instance, a list of Proposed Solutions i.e. alternatives to elements perverting the experience which have been isolated via the interpretation of a test.

The test process and the extraction of feedback from it is very key to producing a meaningful interaction. You may choose to focus group test the product or to pass it around between peers or others you know casually.

It is important not to have strongly defined metrics heading in, but instead to observe the user and their actions, as well as what they say. This is because metrics suggest a predetermined idea of issues within the functionality of system, but, from my experience, you are, as the builder of the system, unable to predict what elements within it which may hinder the desired interaction.

The interpretation of feedback from play testing is a skill which could be covered as an article in itself; however, the ability to listen, common sense, and an understanding of the functionality of video games are all invaluable skills.

Once the team has agreed that the prototype functions as it should with placeholder content, or delivered a vertical slice (a complete playable section of game indicative of final quality), the team must move on to the design and implementation of additional content. The length and complexity of this phase is dependent on the type of project.

Once the content has been designed and implemented then begins the Content Refinement Phase. Dependent on the project this may take more or less time than the Prototype Refinement Phase, but uses the same principals focused purely on how the content functions within the parameters of the core mechanics, as defined during the Prototype Refinement Phase. Large changes to the gameplay should not be made unless absolutely necessary.

After this phase the product is in a strong Beta state and should enter QA with a focus on bug fixing only, after which it is suitable for release.

Project Managing the Iterative Design Process

This methodology focuses on producing a product of high quality, however due to its particular efficiencies it can, when correctly project managed, do so within a controlled time and cost.

The main risk when attempting to scope a project using the proposed methodology is that the time each refinement phase will take is an unknown. In an unrestricted implementation each cycle within a refinement phase is of an indeterminate length and there are an unknown number of iterations.

However, to stop both the time and financial costs of production from spiraling out of control it is suggested that the number and length of cycles with a refinement phase are agreed and fixed prior to the start. Therefore, it is important that before a new build in a refinement cycle is started that all Proposed Solutions are prioritized and then completed in that order so as the most important functional changes are fulfilled first.

However, all other phases, such as content development, can be managed using a traditional waterfall model. By defining strict time frames for each refinement phase (as described above) the project manager is able to give a very defined timeframe and cost for the project.

Scope and Suitability of the Iterative Design Process

Although this methodology is proposed for small teams developing unique video game experiences, it has the flexibility to improve the quality of the experience of much larger, more mainstream video games too. In a larger project, the emphasis would be change — perhaps more toward the Content than the Prototype Refinement Phase.

However, this methodology could suitably be applied to the creation of a proof of concept demo by a small team as a precursor to a larger project, with the feedback from testing placeholder content in the Content Refinement Phase, informing the design of future content.

Its implementation is something that is able to improve the quality of a product in a number of scenarios, however it must be done with thought and concern for the type of team and desired outcome.

Conclusion

Iterative Design Development focuses small, talented teams on finding the correct design to realize a unique and innovative product by building fast and failing fast.

It offers a relatively large freedom and flexibility early on in a production cycle, allowing for a quick and reactive approach to design. It also encourages the collaboration of all disciplines from the start, meaning that teams can start producing straight away, as opposed to one being dependent on the other to finish a task.

It is offered as an evolution of processes refined by Mobile Pie following the construction of numerous products and is informed by our successes and failures, before and after the formation of the company, as well as academic design theory and Agile project management methodology.

I hope that this framework is of use to others in our position and that they may refine and discuss its merits and implementation, further evolving and tuning it for more efficient design development. (Source: Gamasutra)

下一篇:游戏设计师谈团队矛盾应对原则