分析社交游戏病毒传播机制设计的未来

作者:Aki Jarvinen

游戏邦注:本文发稿于2010年4月7日,所涉时间、事件和数据均以此为准。

在本篇文章中,我将提出时下社交游戏设计热议的设计层面相关问题。该层面原本与游戏设计并无关联,更偏向于营销和销售,这就是游戏的病毒性。

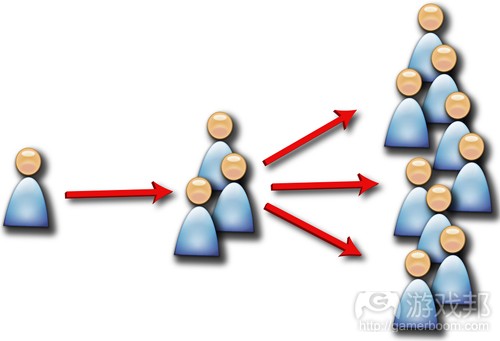

有观点表示,Facebook上的游戏应用称为“病毒游戏”较为恰当,而不是广泛为公众所采用的“社交游戏”的说法。然而用户数是所有病毒性现象的前提条件,病毒式增长通过社交互动方能实现。所以,病毒游戏含有社交性,社交游戏含有病毒性。从某种程度上说,是游戏的开发商和经销商让这两个层面融合在一起。

在这种背景下,Facebook及其交流渠道成为既限制又提供病毒式传播的病毒培养基。在实际运用中,为社交游戏设计病毒式增长模式受网络平台所提供的交流渠道限制,开发商将此套限制条件和机遇整合到游戏玩法中。此时,Facebook之类的社交平台就像是病毒培养基,为游戏的病毒性增长划定了界限。

在这种设计活动中,此类营销方式的差异性来源于营销与游戏可玩性间的有机联系。除非营销人员理解可玩性细节内容,否则病毒性特征便很有可能变成普通消息,只能利用网络的标准交流渠道。营销设计人员需要理解产品的内在运转机制,这与许多其他类别产品并不相同。而且,营销设计人员不可完全按照自己的想法来行事,需要在游戏设计之时考虑到病毒式营销层面。

就开发层面而言,此类设计方案的机遇在于即便平台的交流渠道改变,驱动游戏可玩性的想法仍能保持原样。也就是说,玩家不再只是游戏开发商营销行为所操纵的玩物。刺激玩家病毒式传播的是个人在游戏中的成就或决定,而不是游戏产品本身。

病毒式传播的变革

由于Facebook限定了病毒式传播的形式(游戏邦注:如交流形式和渠道等),社交游戏病毒式设计的创新性几乎不存在或不易为人所察觉。Facebook制定的规范制止干扰性病毒传播行为的产生,从而保护其用户的利益。

随着Facebook平台这个病毒培养基发生改变,病毒式增长的界限也有所改变。游戏的开发并没有使交流渠道得到扩张,反倒使其变得更为狭窄。换句话说,《FarmVille》或Zynga在Facebook病毒式传播风行之初所获得的地位确实已经无可替代。

Facebook Connect和即将出现的Open Graph API(游戏邦注:该接口允许将许多Facebook标准页面功能嵌入任何网页中)是两个矛盾的事物,这两个在Facebook外联结起来的双重病毒式循环可能会萌生更多创新行为。此刻,社交游戏开发商正说服玩家允许他们直接发送邮件。这立马为社交游戏打开了一个直接营销渠道,将病毒培养基扩张至固有的病毒媒介中,正是这些媒介铸就了Hotmail的成功。

不过,我认为即便渠道维持原样,结构和内容也有创新的空间。在Facebook等社交网络及其提供的病毒式交流渠道的背景下,这是近期社交游戏病毒式设计的趋势。

病毒式社交姿态拓宽病毒式传播范围

如果要说社交游戏病毒式设计近期的走向,我认为病毒式传播很有可能模仿普通社交姿态。这并非毫无依据的猜想,竞争性游戏玩法会减少病毒式传播触及的人群及其设计潜力。以某款高竞争性社交游戏为例,如果我们分析玩家在Facebook上发表的故事,除了自我吹嘘、嘲笑他人和比较标准游戏数据(游戏邦注:如等级、分数等)外就没有其他可供交流的内容。

如果游戏玩法和主题带有竞争性,在病毒式设计中采用普通社交姿态的可能性就变得更小,至少游戏的社交触及层面被或多或少地限制在固定品味和社会认同内。游戏事件的病毒性消息只对那些已经在玩游戏或某些玩同类游戏的玩家产生作用。

这可能使得游戏病毒性在小部分群体中增强,但不会自动提供显著病毒式增长所需要的绝对广度,尤其在缺乏社会认同的前提下。社会认同指将他人行动视为合适行为的普遍趋势,将市场意义的病毒性同病理学意义区分开来。

Jesse Farmer从网络理论和病理学的角度来阐述上述问题,将社交网络中的行为机制分为两种:阈值模型(如果有足够数量的朋友在做某件事情,人们也会选择做某件事情)和级联模型(如果有个朋友在做某件事情,人们就有可能去做某件事情)。

无论是何种模型,关键在于人们会跟从其他人的做法。除了可以有效地开展宣传活动,病毒式姿态的社交意义也非常重要。多数朋友可能并不关心你在某款游戏中升级,但此类消息对你那些即将升到这个等级的朋友来说,效果便大不相同。即便朋友没有马上变成游戏玩家,这种祝贺性的社交姿态也很可能加深品牌价值以及好友对游戏的认识,你所玩的游戏在那些已经成为玩家的朋友心中的分量更重。将游戏事件嵌入社交姿态使得病毒式传播有可能循环反复,但这种循环必须有适当的游戏主题、机制和情感潜力方能产生。

社会认同与游戏认同

同时在网络背景下,社会认同的形式正发生改变,不再有某些传统的效果。Facebook游戏应用粉丝页面普遍出现“请添加我”之类的评论。在社交网络中,发挥作用的是互惠友情援助,与游戏相关的友情带来的利益凌驾于传统友情之上。社交纽带并非由游戏产生,游戏本身已成为社交纽带,但可能只在游戏背景中才能发挥作用。虽然这种病毒式帮助并非由多数人的行为构成,但其普遍性仍足以显示出社交游戏中包含的社会认同。任何度过营销著作的社交游戏开发者都知道,这是对老式策略的冲击。

社交姿态的范围已超过竞争性尺度。同时,其扩大了病毒式传播可利用的社交情感范围,因而也会影响到病毒式现象的关键点,如行为适应。如果社交姿态源于游戏,其作用就犹如两人或更多人间的病毒性纽带。比如,用游戏来祝贺朋友在面试中获得成功,如果游戏主题与情形契合,这种游戏般社交姿态可能令接受者印象深刻。此类游戏通常为视频游戏开发商所漠视。《好友买卖》之类的游戏也是游戏玩法同社交姿态结合起来的典型。

总之,病毒式设计近期内有产生变革的机遇,对现有公式化的病毒式增长设计提出质疑。病毒式渠道将探索传播密度和广度间的平衡点,社交姿态将源于社交游戏,为玩家的朋友提供游戏外的含义。

这可能是社交游戏的首个主流文化。一旦实现,我们的病毒式游戏设计便又迈上新的台阶。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The Near Future of Viral Design in Social Games

Aki Jarvinen

In this essay, I want to pose questions about a design aspect which is particularly topical to social game design. This aspect is something that has not been traditionally associated with game design, but rather with marketing and distribution: virality.

It has been suggested that ‘viral games’ characterizes game applications in Facebook better than the widely adopted ‘social’ prefix. Yet population is a prerequisite for any viral phenomenon, and it is through social interaction that viral growth can take place. So, viral games are social, and social games are viral, to the extent that their developers and marketers push them to be.

In this context, Facebook and its communication channels become the viral substrate that both constrains and affords viral spread. In practice, designing viral growth for a social game is leveraging whatever communication channels the network platform affords, and integrating this set of constraints and possibilities with gameplay. The platform, such as Facebook, functions here as the viral substrate that sets boundaries for viral growth.

In this kind of design activity, the difference with marketing as such stems from the organic connection to gameplay – unless the marketer understands the details of gameplay, the viral features are in danger of turning into tacked-on messages that only take advantage of the standard communication channels of the network. The marketer-designer needs to understand the inner workings of the product, unlike with many other product categories. Moreover, the designer-marketer needs to step beyond his/her comfort zone and take the viral marketing aspect into account in the game design.

The opportunity in this, in terms of development, is that even if the platform’s communication channels change, the gameplay-driven message does not change. On the other hand, the player does not necessarily feel very motivated to only function as a puppet marketeer for the game developer. Rather, if there is ever to be an incentive for an individual player to virally spread the word, it needs to be about a personal achievement or decision in the game, not the game product as such.

Innovating with viral

The innovation in the viral design of social games is either nearly non-existent, or goes barely unnoticed, due to the formats – i.e. the communication types and channels – that Facebook forces the virality into. The policies Facebook puts in place function as deterrents to aggressively viral endeavours, thus protecting its population.

As the Facebook platform as a viral substrate has changed, the boundaries of viral growth have changed. The development has been one of narrowing the channels rather than liberating them. This means that, e.g., FarmVille’s (and Zynga’s) status of non-displacement, acquired in ‘wild west’ days of Facebook virality, is literally non-displaceable.

More substantial and disrupting innovation might come from the double viral loops that connect outside Facebook – paradoxically, through Facebook Connect and Facebook’s upcoming Open Graph API that allows many of the standard page functionalities from Facebook to be embedded into any page in the web. As we speak, social game developers are persuading players to give permission to email them directly. At once, this opens up a direct marketing channel for social games, and expands the viral substrate to an inherently viral medium – the substrate behind the success story of Hotmail, after all.

Nevertheless, I believe there is room for incremental innovation, both in terms of structure and content, even with the channels in place at present. This could constitute the near future of viral design in social games, at least in the context of a social network like Facebook and the communication – i.e. viral – channels it affords.

Epidemic social gestures unlock viral breadth

If there is a near future of viral design for social games, my argument is that it is in modeling the viral feeds more strongly towards general social gestures.

This postulation is based on a starting hypothesis, according to which competitive gameplay reduces viral reach and its design possibilities. If we take a highly competitive social game and analyze the Facebook stream stories it persuades players to post, what is there beyond bragging, taunting, and the standard quantitative game data (levels, points, etc.) that can be communicated?

When the gameplay and theme are inherently competitive, the possibilities to adapt general social gestures to viral design become more narrow or at least their social reach stays within more or less fixed boundaries of taste and social proof. Viral messages about game events remain meaningful only to those already playing the game, or someone playing a very similar game.

This might give the virality some density within a closely knit group, but it does not automatically provide the absolute breadth required for significant viral growth, especially if it is bordered with lack of social proof. Social proof refers to general tendency to see an action as more appropriate when others are doing it. It is something that differentiates viral in the epidemiological sense from viral in the marketing sense of the word.

Jesse Farmer approaches the same issue from the perspectives of network theory and epidemiology, and identifies two mechanisms of behavior adoption in social networks: The Threshold Model where people do something if enough of their friends are doing it, and the Cascade Model i.e. that people have a chance of doing something if one of their friends is doing it.

Whichever the model, the persuasive means to follow other’s actions are crucial. Besides effective copywriting, it is the social meaning of the viral gesture that is important. Majority of your friends might not care less if you got to level 32 at game X, but what if that leveling up stream story would guide you to dedicate it to a friend of yours who is about to turn 32? Even if your friend would not convert into a player instantly, the social gesture of congratulating more likely gives your game a positive tilt in terms of brand value and recognition – your game stands out from the spam in the mind of the yet-to-be player who is your friend. Embedding game events into social gestures presents a chance for a viral loop of social goodwill, but it has to sprout organically from your game’s theme and mechanics, and their emotional potential.

Is social proof viral proof?

On the other hand, the forms of social proof are changing in online, networked contexts, discounting some of the traditional effects. A common comment from any fan page of a Facebook game application goes: ‘Add me please level 19 play daily’. In a social network that is supposed to work according to a reciprocical friendship principle, the benefits of game-related friends are over-riding traditional common nominators of friendship. It is not that games are creating social ties, games are becoming social ties, but possibly strong and lasting only in the game’s context. Such viral befriending is not constitutive of the behavior of the majority of population, but it is still common enough to warrant a reality check on how social proof is evolving in social games. As any social game developer who has read marketing classics knows, this is a punch to the gut of the old tactics.

The broader spectrum of social gestures reaches beyond the competitive dimension. At the same time, it expands the array of social emotions the virality can tap into, thus also affecting the gist of viral phenomena, i.e. behavioral adoption. Doing favors and reminiscing are examples of social gestures that, when originated from a game, function as a viral address between two or more people. For example, using a game to wish your friend luck with a job interview is a game-driven social gesture that might leave a lasting impression to the receiver, if it is in line with the theme of the game. It is telling that the types of games (e.g., Friends for Sale) often disregarded as ‘real’ games by video game developers show signs of the approach described above. Games like Friends for Sale also marry gameplay with social gestures rather than routinely stylizing fantastic – or perhaps more appropriately ‘farmtastic’ – actions into game mechanics.

In conclusion, the near future of viral design holds opportunities for experimentation, perhaps even creativity, that question the existing, formulaic means to create viral growth. The balance between density and breadth can be explored with a repertoire of viral channels, but also with social gestures unleashed within them as stream stories and requests, originating from a social game and injecting the player’s friends with a meaning outside the game, and thus beyond spam.

This might open the floor for the first truly mainstream meme from a social game that goes beyond stream stories and parodies. Once that happens, we have arrived at the future of viral game design. (Source: Gamasutra)

下一篇:社交游戏改变传统“游戏玩家”定义

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号