《游戏作弊》:游戏玩家对作弊现象的双重道德标准

游戏邦注:本文原作者是坦佩雷大学的超媒体、数字文化及游戏研究教授Frans Mäyrä,他从游戏的“亚文化圈”和文本攻略这两个方向入手,对Mia Consalvo所著的《游戏作弊》一书中的“游戏资产”等观点发表了评论,引导人们了解游戏作弊现象的成因,以及玩家自身对游戏作弊现象的不同态度。

随着游戏调查研究领域的日趋成熟,针对游戏、游戏行为和玩家的有效而方向各异的研究方法也开始大量涌现。

其中一种方法是指在大环境影响下的游戏文化研究。无论是在英国还是美国,人们在研究文化传统上,都热衷于从政治、经济、社会以及文学角度追根溯源,他们在这些高度跨学科领域中寻找只言片语的内容从而增进对流行文化的理解。

英国早先的文化研究特点深受部分马克思著作、左翼分子批判资本主义社会和文明产业等文献的影响,而美国文化研究方式更像是在壮大广大民众的自由民主呼声,发动群众游行。如今,这两种研究方法的差别已日趋模糊。

俄亥俄州大学电子通信学院的研究生导师及副教授Mia Consalvo在她的书中提到了关于六年前研究游戏作弊的内容,使读者更好地了解这个话题。她所著的《Gaining Advantage in Video Games》(2007)一书在调查研究“游戏作弊”方面没有让广大读者失望。

当然,这本书不单单是介绍游戏作弊的形式和手段,它也为游戏文化分析的意义以及如何开展这类游戏研究提供了参考内容。在这篇评论中,我的主要目的是讨论这本书两个方面的内容:我们可以从游戏以及游戏作弊现象中获得什么信息?文化手段运用的利弊是什么?

这本书的开篇主要从两个方向入手进行论述:

事先通过查阅攻略进行作弊与玩家通过自行摸索相比,游戏所带来的刺激感和愉悦感会大打折扣。但许多游戏玩家对自己的这种作弊方式很宽容,但却无法容忍其他玩家采取同样的行动。

往往我们在游戏中作弊的时候,会有一个特殊的双重标准或者说双边道德。Consalvo在书中为我们阐明了许多游戏作弊的方式以及游戏作弊的潜在逻辑。

关于游戏作弊的历史由来已久,这种现象的存在甚至可能比整个人类发展史还要悠久。此外,它的流传之广、地位之重要甚至在最古老的艺术和文学作品中都有章可循。

Consalvo引用了J. Barton Bowyer(实际上J. Barton Bowyer这个名字是历史学家J. Bowyer Bell和政治军事阴谋家Barton Whaley名字的合体)作品中的观点,指出了“游戏作弊”在《伊利亚特》(游戏邦注:相传这是荷马所做的古希腊史诗,描述了古希腊人利用特洛伊木马计获胜的事件)中的重要性。尽管“游戏作弊”这种禁忌手段通常会被人嗤之以鼻,然而,一旦这种手段被我们中所认同的一方(尤其是这一方遭遇许多强敌时)加以利用,它就转变成了一种令人称道的高明手段。

与其说“游戏作弊”违反了游戏规则,不如说它是重新定义游戏规则从而“扭转乾坤”,让原本无法继续下去的游戏出现转机。从Consalvo的研究角度来看,游戏作弊行为分析的公开化无疑是一个非常引人注目的有趣话题。

Consalvo在这本书中介绍了影响其调查研究的两个核心概念,首先是“游戏资产”,它是社会学家Pierre Bourdieu所提出的“文化资产”的变体与延伸。“文化资产”最初被认为是一种在具有良好教育的家庭中形成的无形资产。正如Consalvo在书中所提到,“游戏资产”同“文化资产”相比在范围和功能上具有一些细微的差别:

贯穿全书的其中一个主题就是游戏资产的发展是游戏玩法的核心要素。我认为,游戏资产的概念有助于人们理解个人如何与游戏、游戏信息、游戏产业以及其他玩家相互沟通。游戏资产是一个很有用处的术语,因为它可以解释一种存在于各种类型玩家或游戏,并且随着时间不断发展的货币。

对Consalvo来说,游戏资产是探讨数字游戏中的角色知识、经验以及技能对个人的重要性,以及与其相关的更大范畴的文化和经济体系的重要切入点。

她更明确地将其表述为一种对“亚文化”这种存在不足之处的文化研究概念的补充。假如一群游戏玩家组成一个“亚文化圈”,也就表示他们拥有共同的思维、行为和表达方式,这些都是他们属于某一特定社会文化群体的标志。

Consalvo提到角色扮演游戏玩家和大型多人在线角色扮演游戏的粉丝时,特别举例到,《EverQuest》这款游戏潜移默化地使玩家们形成了一种“亚文化圈”。但她质疑《反恐精英》是否实实在在地属于游戏亚文化圈中的一员。

鉴定“亚文化圈”,就是要看一个群体是否在诸如时尚,音乐或者美学等层面拥有共同的追求和标志。

因此,Consalvo认为一种“亚文化圈”需具备有外在的可见性因素,比如服饰,或者生活方式等方面的共同点。而我更加感兴趣的是,文化交流中不可见的因素,例如语言,文化礼仪,思维方式。从而就可以很容易地想到那些第一人称射击游戏的粉丝,正是研究人员探索亚文化圈形成的有趣调查样本。当然我也非常赞成Consalvo所说的,无论是从个人意义的微观层面还是整个西方社会的宏观层面,我们都需要区别讨论游戏玩法中有价值和意义的内容。

Consalvo在书中较早提出的第二个关键概念产来自于法国理论家Gérard Genette的“侧文本”理论。对于文学作品而言,侧文本可以是任何不涵盖在“主文本”中的内容,它是与封面、简介、目录相类似的成份,但人们始终无法明确它的定义。

也许很多人会说,具有网络时代烙印的文本文档、各种媒介的流体混合以及电子出版物的大行其道,已经很难使人们将侧文本与原文本区分开来。Consalvo提到Peter Lunenfeld 认为数字媒体中的侧文本有时也会比原文本更加生动有趣。

按这条思路看,就有人会说《游戏作弊》这本书主要关注的并不是游戏本身(因为该书并没有对游戏做大量的分析考察),倒是写了很多游戏周边的活动和内容。难道作为一本关于游戏考察的书籍,《游戏作弊》偏离主题了吗?我并不这么认为。

Consalvo在书中的最后章节,构建了一幅丰富详细的图景。通过审视各种边缘现象,使我们了解到什么是游戏以及游戏对玩家的意义。文化建立在有意义的事物之上,而构建具有意义的活动需要有独到的能力。到底怎样的游戏才适合自己?到底玩家们在游戏中排斥什么内容?“游戏作弊”这个话题的确发人深省。

该书分为三个部分: 第一部分题目是“游戏作弊的文化与历史”;第二部分是“游戏玩家”;第三部分是“资产和游戏道德”。这本书中重点描述了形形色色的“作弊产业”,这一点看起来也似乎有点脱离主题,但Consalvo还是在最后章节承认她忽略了玩家创造内容这个层面的讨论。接下来是关于自由通关,在线攻略和网络论坛交流以及免费帮助软件的简短讨论,但坦白说,《游戏作弊》更像是一本组织严密、带有商业色彩的介绍游戏文化的作品。尽管该书主要侧重讨论商业形式的欺骗手段,不过要注意的是Consalvo的目的在于让我们辩证地理解与欺骗相关的产业活动和游戏活动。为此,她做了大量的收集工作,例如玩500小时的游戏,或是参加在《最终幻想XI》(Square, 2002)服务器上进行的研究考察。

此外,为了深入了解不同形式游戏作弊的手段和态度,她还进行了24小时的深度采访。她还对50名游戏玩家进行了开放式调查,并将该调查作为研究生课程的一部分。她将所有考察到的资料和信息整理成书,构成了一套游戏文化与游戏相关产业的辩证分析报告,以便重新定位和解读不同游戏侧文本中日渐具体化的作弊手段。

游戏新闻界的主要侧文本在是该书第一章节的主题。在那一章中,Consalvo主要关注的是任天堂杂志《Nintendo Power》。《Nintendo Power》作为任天堂在北美区域的首要官方资讯杂志,从行业角度看,它是游戏产业发展的重要助推器,它在打小就玩任天堂游戏的北美玩家生活中扮演着游戏文化教育者这一重要角色。

以透露任天堂游戏内部信息以及详细游戏攻略的《Nintendo Power》让很多北美读者学会鉴别视频游戏的好坏,也培养了他们的游戏资本价值观。杂志中的“秘密信息”专栏公布作弊码正是游戏资产组成的一部分。该杂志将是否在游戏中利用作弊码的选择权交给了读者玩家,它还包含了玩家提供的意见和建议,这就逐渐培养了玩家在游戏文化中的参与意识,正因为玩家们可以随时获得并展示他们不断增长的资产。Consalvo于是对玩家文化和产业需求之间的辩证关系进行了研究:

作为《Nintendo Power》游戏攻略的早期组成版块,“秘密信息”和“顾问角落”共同培养了一个掌握了相当数量游戏资产的玩家: 这类玩家了解即将推出的新款游戏及其内容;即将上市的游戏硬件将有哪些优势;要赢得多少分值才算是高分;哪一个作弊码适用于最新游戏;为什么这款游戏的控制系统和视觉效果等元素非常重要;某一款特定游戏的闯关攻略。这种骨灰级的游戏玩家才会成为理想的游戏及游戏杂志消费者,并由此推动游戏行业的不断发展。

Consalvo同样提到了关于“复活节彩蛋”的话题,程序员在游戏代码中偷偷植入“神秘礼物”以增加游戏的趣味性。游戏开发者有时通过这种手段“欺骗”游戏发行商,作弊的领域真是越拓越宽啊!Consalvo并没有在深入挖掘这个话题,不过越来越多相似的例子和欺骗手法都强调了“游戏行业”、“玩家”或“客户”三者之间相互交织的复杂性。很明显,游戏产业中存在不同派系,他们有时为各自的利益争斗。游戏玩家也同样如此,一个玩家的所获得的快乐往往建立在另一个玩家的痛苦之上。就比如“破坏游戏”这个行径(各国玩家对某一个专门以制造破坏为乐的家伙的重重声讨,谩骂或者抱怨),还将会在下文多次提到。

视频游戏的文本攻略是《游戏作弊》讨论的第二主要内容。

Prima Publishing (现名Prima Games)是兰登书屋旗下的一个部门,自称是“世界领先的PC和掌机视频游戏攻略内容发行商”。

另一个主要游戏攻略发行商是Dorling Kindersley/DK Publishing旗下的BradyGames。 Consalvo通过观察攻略图书产业的演变史得出一个结论——大批非官方游戏攻略逐渐销声匿迹,随之而来的是官方授权的正版游戏攻略刊物。

官方攻略的形式和内容大体上遵循既定风格——大量的游戏图片与游戏玩法、角色等级、武器装备以及其他相关通关信息。Consalvo主要关注的是如何将通关秘诀与主要攻略区分开,以及官方攻略如何避免出版游戏作弊码。

她在上述方面的研究考察极具启蒙意义,并指出通关攻略也在小心翼翼地维护“正确合理的游戏玩法”。而游戏开发商和游戏攻略作者自身时常借助强大的作弊码快速通关的内容,却并没有记录在对外发行的游戏攻略里。Consalvo指出,这些作弊码其实是游戏开发商提供给游戏攻略撰写人和游戏杂志而制作的。在游戏的生命周期即将走到终点时,游戏开发商可能就会想法发布这些作弊码,以鼓励玩家“为即将结束的游戏寿命注入新的能量”;无论是游戏攻略还是作弊码都会鼓励玩家回访游戏,让他们发现之前隐藏的奖励,例如额外任务,秘密区域以及现今复杂游戏所携带的迷你游戏。

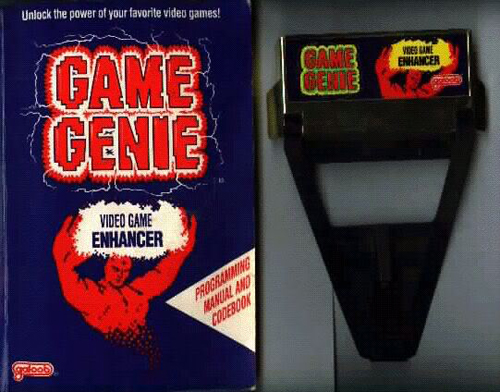

第三个主要部分是《游戏作弊》书中引述到的“侧文本“产业。该产业目前正在盛产一种硬件设备,能够使玩家在游戏进行时获得好处。Game Genie这款由CodeMasters设计,美国Galoob Toys公司和Camerica公司共同销售的游戏作弊设备就是一个很有趣的研究案例。

Game Genie自称能够为玩家提供额外能量的“游戏优化”设备,可帮助游戏玩家所扮演的Mario角色获得无限生命值或者是跳过某一关卡等作弊手段。

Consalvo着重讨论了任天堂和Game Genie制造商之间的法律纠纷:任天堂声称这款设备的衍生物涉嫌侵权。一款能够修改游戏设置的设备很可能正如任天堂所说降低游戏可玩性(通过将游戏设置简单化)。

最终Galoob公司胜诉,任天堂需赔偿Game Genie制造商损失的销售额。这场官司可以解读为,只要用户是通过合法途径获得游戏,这款游戏就属于用户的私有财产,他们可以通过任何手段修改游戏。

然而,在另一个关于“芯片改装”的案例中,法律案件的矛头却指向了芯片的改造者。“改装芯片”主要是用于绕过嵌在游戏机里的权限,但它的作用并非在游戏中添加新功能,而是使游戏或媒体运行于其他市场(即地区代码破解),或者是避开拷贝保护(制造盗版、非商业用途的自制游戏)。Consalvo并没有在她的研究报告中表明立场,不过她在采访中得到的数据分析显示,这种游戏优化设备在玩家群体中并不是很招人待见。她还提到,为了维护自身利益,索尼等游戏机设备及游戏开发商必须力阻游戏开发技术的透明化,所以才对用户提出了“不要使劲敲击机器,只播放正版碟片,每隔大约5年重新购买设备”等要求。对于科技优化的过度信赖很有可能在无形中减少玩家的游戏资产,但资深玩家仍然可能凭借其知识和技能优势,掌握更具竞争力的游戏资产。

游戏作弊的法律争论起源于商业利益的驱使,因限制游戏技术而获利的一方,以及通过自由“优化”游戏而受益的一方总是在这个问题上彼此纠结不已。

游戏玩家也出于各种动机对与作弊持有不同的态度。

Consalvo将这些态度分组,最终构成了两个完全不同的作弊道德经济体系:第一个是单人游戏,第二个是多人游戏。第一种情况里面,玩家只需要根据自己的心意来玩游戏。

Consalvo将单人游戏中的作弊态度划分成三种类型:首先是“纯化论者”认为除非是凭借个人力量完成游戏,否则就算是向朋友讨教游戏攻略也是作弊。第二种类型的人认为透露游戏信息、钻漏洞或者用作弊码的行为都是不正当的,这会使游戏顿失挑战性。不过,寻求攻略或游戏指导还是能够被理解的。因为它们本身不会“破坏整个游戏规则”。第三种类型,绝大多数自由论者认为在单人游戏里,规则由玩家自己来制定,所以就算是把游戏代码全换掉都不算作弊。除非与别的玩家共同游戏时,这种行为才算得上作弊。他们不过是在玩游戏时,加入了更多的选择。这些选择有时使得原先的游戏更加有趣,有时也会使游戏的精彩程度减色不少。讨论游戏作弊与否的一个主要方法就是为其设上一个标准:什么时候可以作弊,什么时候不可以作弊。当玩家在游戏中走投无路的时候,可以允许他们作弊。当玩家手头时间不充裕,而又很想玩到游戏的最后一关,这时候可以允许他们作弊。而有些人作弊的原因仅仅是出于好玩,因为他们觉得修改后的游戏会带来全新的游戏体验。

在多人模式游戏领域,游戏作弊的本质则有所变化。Consalvo决定首先将“破坏游戏”这个行径与其他形式的游戏作弊区分看待: 对于游戏破坏者而言,他们只通过破坏游戏获得快感,即把自己的快乐建立在他人的痛苦之上。换句话说,他们玩的是其他游戏玩家,而不是游戏本身。因此,他们这种行为的本质与别的玩家不同。(就算他们只是天性顽皮,开开玩笑而已。)作弊以及这种行为在匿名环境中的在线游戏领域中表现尤为明显。Consalvo指出,传统的线下游戏会采用一些机制让不同水平的玩家进行更势均力敌的对决。但在线游戏领域并不具备这种元素,所以一些玩家只好在多人射击游戏中使作弊行为合理化,或者在MMORPG中使用真实货币购买道具以获得战略平衡。

在线游戏中的普遍作弊行为使许多玩家丧失斗志而转战其他游戏。因此,在线游戏运营商一直在和这些作弊者玩着猫捉老鼠的游戏。多人游戏的作弊方式与此大同小异,并且层出不穷,花样迭出。在《游戏作弊》一书中,作弊的方式被分为四大类:利用游戏漏洞,利用玩家,利用游戏代码,利用第三方系统。

Mia Consolva的书中涉及大量关于人类创新性的研究案例,具有丰富趣味性的历史和当代例子不胜枚举。很显然,她对游戏及其玩法的研究,也会引起其他学术领域研究者的兴趣。但我认为,那些悬而未决的讨论话题可能才是是Consalvo书中最有趣的部分。游戏作弊是不是一种特意为之的活动? 是不是因为游戏作弊,才产生了欺骗者?游戏文化乃至人类文明和社会中的孰是孰非是如何产生的?就这一点来看,《游戏作弊》中或明或暗地引出了一些讨论。例如,关于“魔法阵”的讨论,游戏和游戏玩法中“沟通”的重要性。一方面,关于“游戏设计道德”的讨论;线上线下玩家行为和身份的伦理关系。学术领域对游戏作弊及其相关主题的兴趣仍在持续升温,Mia Consalvo的这本书为这些讨论又提供了一项可贵的参考价值。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,转载请注明来源:游戏邦)

Gaming Culture at the Boundaries of Play

As the field of game studies and research has matured, multiple valid, yet somewhat differently oriented approaches to games, play and players have emerged. One of them is the cultural study of games and play related phenomena. Both the British and American traditions of cultural studies have been particularly interested in advancing our understanding of popular culture by tracing its position and significance from perspectives opened up by politics, economics, sociology, as well as by literary or textual studies, to mention just a few elements from this highly interdisciplinary field. Where the hallmark of British cultural studies used to be reliance on some version of Marxism or left-wing critique of capitalist society and its cultural industries, and the American approach to cultural studies was more likely to develop liberalist analyses of empowered audiences, or fandom activities, this divide does not stand out so clearly these days. While approaching Cheating by Mia Consalvo, it is nevertheless useful to be keep in mind such intellectual traditions and debates.

Mia Consalvo, an Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies in the School of Telecommunications at the Ohio University, reports in her book the results from six years of work on the theme of cheating, so the reader can expect a well-informed account of the topic, and in this respect Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Video Games (2007) does not fail the expectations. The study is nevertheless more than just an introduction to the forms and practices of cheating in games. It is also a useful example of what cultural game studies could mean and how this line of research can be carried out. In this review my aim is to address these both dimensions of the book: what does it teach about games and cheating, and what does it tell us about the strengths and weaknesses of a cultural approach.

The starting point of Consalvo in her book comes from two directions: both the personal memory of ‘cheating’ by secretly searching out a Christmas present (an Atari 2600) before its due time as a child, and the later observations about the widespread distribution and use of walkthroughs, cheat codes, and other means in contemporary gaming culture contribute to the initial sense of paradox, which book then proceeds to examine further. Cheating by looking up the solution (or a Christmas present) beforehand, will spoil the surprise and joy of finding things out in their proper way later, yet the practices of cheating are something that many of us will tolerate in ourselves, but not necessary in others. There is a particular dual logic or double moral at play while we cheat in games and Consalvo’s book makes a valuable contribution both by mapping out the many forms of cheating, as well as by carefully unravelling the underlying logic of cheating.

The cultural history of cheating is long, as this phenomenon has perhaps existed longer than the entire human history, and even the most ancient artistic and literary sources carry evidence about its widespread use and role in the society. Consalvo makes reference to the work of J. Barton Bowyer (actually a joint pseudonym of J. Bowyer Bell and Barton Whaley, a historian and a military-political deception theorist) to point out the role cheating had in the Iliad, where the Greeks gained victory through the famous ruse of Trojan Horse (see Bowyer 1982). Generally a forbidden and scorned practice, cheating has the propensity to suddenly become clever and admirable behaviour when used by a party we identify with, particularly to ‘even out the odds’ when faced with a vastly superior opponent. Rather than breaking the game, cheating can be read as an act that redefines the rules, ‘turns the tables’, and makes it possible to continue with the game. From the perspective of Consalvo’s study, this openness to interpretation in cheating behaviour is a particularly interesting theme to focus on.

The two key concepts that Consalvo introduces early on in her book point towards the central theoretical directions for influences in her research, textual and sociological. The first is ‘gaming capital’, which is an extension and reworking of sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s ‘cultural capital’ – originally conceived as a concept to describe the intangible benefits growing up in a well-educated family, for example, can provide to a person (see Bourdieu 1984). As proposed by Consalvo, gaming capital has a slightly different scope and function:

Thus, one of the themes running through this book is the development of gaming capital as a central element to serious gameplay. [...] I believe that the concept of gaming capital provides a key way to understand how individuals interact with games, information about games and the game industry, and other game players. The term is useful because it suggests a currency that is by necessity dynamic – changing over time, and across types of players or games. (Consalvo 2007, 4.)

Gaming capital is for Consalvo a way to discuss the role knowledge, experience and skill have both for an individual, but also for the larger cultural and economical system that surrounds digital games. She particularly frames it as a response to the shortcomings of another key concept of cultural studies, ‘subculture’. If a group of players would constitute a subculture, that would mean that they share some ways of thinking, behaving and speaking that would identify them as members of a particular, cultural and social formation. Consalvo refers to role-playing gamers and fans of MMORPGs like EverQuest in particular as potentially constituting a subculture of their own, but she wonders whether an avid Counter-Strike player could be fruitfully described as a member of a gaming subculture. “A subculture, to be identified as such, must share common symbols, through such things as fashion, music or aesthetics” (p. 3). Thus, for Consalvo, a subculture needs to be externally visible e.g. in clothing, or integrate with an overall lifestyle in order to make sense. In my own view, I would be interested in studies that explore also the more invisible aspects of cultural bonds, including language, ritual and thought patterns, and thereby could rather easily imagine that the first-person-shooter fans, for example, could reveal interesting subcultural formations for a committed researcher. But I also respect Consalvo’s basic argument about the need to distinguish and discuss those aspects of value and significance in gaming practices that link the micro level of individual players to a more macro level of Western, industrialised society.

The second key concept that Consalvo introduces early on is ‘paratext’ by Gérard Genette, a French literary theorist. For a literary work, paratext can mean the book covers, blurb, table of contents or other similar elements that are not parts of the ‘authorial text’, but nevertheless frame it and influence how readers will approach and interpret it (Genette 1997). It can be argued that hypertextuality and the fluid (re)mixing of various media elements that is typical for the era of Internet and digital publishing makes it increasingly difficult to separate paratext from ‘originary’ texts. Consalvo makes reference to Peter Lunenfeld (p. 9) to argue that in digital media the paratexts are also often more interesting than the originary texts. Following this line of thought, one could claim that the main focal point in Cheating does not lie within games themselves (there are no extensive game analyses, for example), but at the various activities and elements that surround them. Should the book then be considered as off-topic, if taken as a work of game studies? Not to my mind; in the end Consalvo manages to construct a rich and detailed picture of what games are and mean for their players, by looking at various borderline phenomena. Culture is based on meaning, and meaning-making activities are based on an ability to make distinctions. Cheating is a revealing topic, since it makes visible what players actually consider as ‘proper gaming’ and what they attempt to exclude from it.

The book is divided into three main parts: the first part carries the ambitious title “A Cultural History of Cheating in Games”, the second is titled “Game Players” and the final, short part “Capital and Game Ethics”. There is a clear emphasis in the book on the various ‘cheating industries’, which is something that could also be interpreted as a tilt – an issue that is openly addressed at the end of the book, where Consalvo admits largely omitting discussion of player-created content (p. 176). A short discussion of free walkthroughs, online guides and Internet forum discussions and free help software follows, but it is fair to say that Cheating is more a book on the organised and commoditised forms of gaming culture, than about its informal and immaterial aspects. This is no doubt partly a consequence of methodological feasibility: elements like cheat guides are more immediately open for analytical approach than the spontaneous acts of cheating that would require extensive observations for a long duration of time. While the emphasis of the book lies on industrialised and commoditised forms of cheating, it is important to note that Consalvo is aiming towards a dialectical understanding of industry and player activities that relate to cheating. Her most substantial field work consists of more than five hundred hours of gameplay, or participant observation, carried out in one of the servers of Final Fantasy XI (Square, 2002), a moderately popular MMORPG that is part of the Japanese Final Fantasy franchise (p. 150). In addition, twenty-four in-depth interviews were carried out to gain a better understanding about the practices and attitudes towards cheating in its various forms; Consalvo also reports having carried out an open-ended survey of fifty game players as a part of an undergraduate course (p. 86). All this information is used in the book to construct an analysis about the dialectic of gaming culture with game-related industries, particularly in order to situate and understand cheating as it is concretised in various paratexts of gaming.

The particularly central paratext of games journalism is the topic of the first chapter, where Consalvo has chosen to focus mostly on Nintendo Power magazine (established in 1988). As the official magazine of Nintendo in North America, Consalvo discusses its role as a promotional tool from an industry perspective, but puts most emphasis on the educational and cultural roles the magazine served for the American players growing up with Nintendo’s games. Famous for its insider information into Nintendo games and for publishing detailed strategy guides, Nintendo Power was according to Consalvo a major factor in educating American gaming audience about what was good and bad in a video game, and for articulating and cultivating sense of value in gaming capital. The tricks and secret codes published in the “Classified Information” section were one element of that special currency gaming capital was built of. The magazine let it up to players themselves to choose whether to use the cheats in their actual gameplay or not – the insider information held some special value and status in itself. Nintendo Power also included tips and input from their readers, thereby cultivating a sense of participation in game culture, as gamers were able to gain and display their own growing capital. The dialectic between gamer culture and the needs of industry is taken into focus by Consalvo:

Such early elements as its [Nintendo Power’s] game guides, “Classified Information,” and “Counsellor’s Corner” (among many others) worked together to help create a game player who possessed critical pieces of gaming capital: the player knew about the newest soon-to-be-released games and their general content; what advantages were coming in game hardware; how high a high score should be in order to be impressive; what secret codes and tricks could be used in the latest games; why such elements as controls and graphics were important; and how to play and finish specific games. That power gamer would become the ideal consumer of games and game magazines, and has shaped how the game industry has responded. (p. 32-33.)

Consalvo discusses also the issue of ‘easter eggs’, the secret items or elements in games that most often an individual programmer has secretly hidden inside game’s code to make a joke or some personal statement. As these sometimes constitute the makers of game ‘cheating’ on their employer (or the game publisher), the field of cheats expands even further. Consalvo does not delve on this point, but the multiple instances and levels of cheating actually highlight the complex fraction lines within such, often rather homogeneously understood concepts as ‘games industry’, ‘players’, or ‘customers’. There are clearly several differently positioned parties within games industry, sometimes with conflicting interests. And similar holds also true regarding game players: another player’s fun might be another one’s spoiled game – as is often the case in so-called ‘grief play’ (intentional harm, abuse or harassment of other players for one’s own enjoyment), which will be discussed more below.

The paratextual field of strategy guides for video games is the second key area Cheating discusses. Prima Publishing (currently named Prima Games) is a division of Random House, Inc., and calls itself at “the world’s leading publisher of strategy content for PC and console video games”. Another major guide publisher Consalvo discusses is BradyGames, which is currently part of Dorling Kindersley, or DK Publishing, itself a division of Penguin Group. Consalvo follows out the evolution of strategy book business, and concludes that unofficial guides have largely vanished from the market, as guides have become an officially sanctioned and licensed part of game publishing. The format and content of guides generally follows proven formulas of combining lavish illustrations with the gameplay basics, character class, weapon, armor and other item information, plus the actual walkthrough parts. Consalvo pays attention to how the secret or ‘spoiler’ elements are typically separated from the main walkthroughs, and also how the official guides do not generally publish the actual cheat codes. This part of her analysis is particularly enlightening, as it points out how the ‘proper way to play’ is carefully constructed even in the guidebooks: the most powerful cheats such as those codes (immortality, ‘god mode’) which the game developers and guidebook authors themselves often resort to while quickly playtesting certain parts of the game, are not included in the guides directed to the consumers. Consalvo describes such codes as specific commodities that hold value within the deals that game producers commonly make with the guide writers and game magazines. At the end of the lifespan of a game the cheat codes might be published to “breathe continued life into aging games” (p. 62); both the guidebooks and cheat codes might be used to encourage players to revisit the games, and explore them in order to find all the hidden bonus materials like side quests, secret areas and minigames which today’s complex games are designed to hold.

The third major area of ‘paratextual industries’ which are introduced in Cheating are producing the add-on devices that are used and marketed for gaining advantage in games. Game Genie cheat cartridges, which were designed by CodeMasters and sold by Galoob Toys in the USA and by Camerica in Canada and the UK, provide an interesting case study. Advertised as “game enhancement” devices that provide “extra power” to the gamer, Game Genie for Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) made possible for a console video gamer to gain infinite lives for her Mario, or allow level skipping or some other cheat. Consalvo highlights the legal battles between Nintendo and Game Genie producers: Nintendo claimed that the device created “derivative works” which infringed its copyrights (p. 67). Dispute was ultimately one about control over gaming experience. A device that allowed the modification of ‘authorial text/gameplay’ might shorten the life span of games the way Nintendo claimed (by making play ‘too easy’), but ultimately the issue revolved about control over gaming content. Galoob won the court case and Nintendo was ordered to pay compensation for lost sales to game enhancer makers. This can be interpreted to strengthen the position that game, once legally acquired, is customer’s property and she can use whatever means available to modify her gaming experience. However, in the later case of ‘mod chips’ the legal cases have generally turned against the modders; mod chips have been developed to circumvent built-in restrictions in gaming consoles at least from original Sony PlayStation onwards, but rather than enabling new functionalities in (legal) game copies, mod chips are generally used to run games and media intended for other markets (region code hack) or circumvent copy protection (running pirated or non-commercial, homebrewed games). Consalvo does not take sides in the disputes she documents, but she notes that her interview data points towards relative unpopularity of enhancement devices among game players (p. 75). She also points out that it is in the interests of console and game manufacturers like Sony to make gaming technology opaque – the proper technology use involves “not cracking open machines, playing only properly purchases [sic] disks, and buying a new generation of machine every five or so years” (p. 78). The overreliance to enhancement technologies has also the ambiguous role of potentially reducing one’s gaming capital, while some proficiency in this area could be expected from a competent and knowledgeable gamer.

The legal debates on cheating have been driven by commercial interests, either of those who would profit from closed and restricted gaming technologies, or of those companies who would profit if “enhancement” of games is freely allowed. The approaches and stances of gamers themselves towards cheating in games have been somewhat differently motivated. Looking at her evidence, Consalvo separates groups of attitudes that actually constitute two different moral economies in cheating: the first is applied to single-player, the second to multiplayer games. In single player games the situation is more one of player negotiating with her own conscience, and is based on an understanding of what constitutes ‘proper gameplay’. Consalvo divides the attitudes towards single-player game cheating in three groups: firstly, the ‘purist’ considers as cheating anything other than getting through the game all on your own. Even asking for advice from a friend would be considered as cheating within this moral system. The second group considers as ‘unfair advantage’ any exploit, hack or cheat code that would somehow alter the challenge, as originally designed into the game. But consulting a walkthrough or guide would be allowed, since it does not ‘break the game’ itself. Thirdly, the most liberal group thinks that cheating is only possible when it is directed towards another player – in a single-player situation the norms are created by the player herself, so even radical alterations of game code are not cheating. They just constitute alternative ways of playing that are sometimes more fun, sometimes less, than the designer- or manufacturer-imposed intended style of gameplay. (p. 88-92.) A typical way to negotiate cheating involves setting up boundaries which dictate when cheating is allowed and when it is not. When one has tried hard, and yet cannot get ahead in a game, would grant a ‘license to cheat’ for many gamers. For some, the fact that they are in a hurry and cannot afford to use tens or hundreds of hours of their time, in order to get and see the end of game they have purchased would be reason enough for resorting to a cheat. Some use a cheat just because it is fun: a modified game provides a different kind of game experience.

In a multiplayer space the nature of cheating changes. Consalvo has decided to separate grief play from other forms of cheating: the primary goal of griefer is not to gain advantage within the game, but rather to derive pleasure by spoiling the game for others. The griefers ‘game the players’, rather than ‘play the game’, and thus the fundamental nature of their actions is different from other players (even while it still might be ludic, and playfully motivated). The range of cheating and motivations for those behaviours is great particularly in the largely anonymous field of Internet gaming. Consalvo points out that in traditional offline situations there are mechanisms that are used, for example, to negotiate handicaps that allow players with different abilities to compete more evenly with each other. In the online space typically no such elements exist, and thereby some players rationalise the use of cheats in multiplayer shooters or the use of real money trading in MMORPGs as fair practice, since they perceive it as a technique to even up the different potentials for success. As a prevalent practice, cheating in online games may nevertheless lead to increasingly demoralised players who will stop and move elsewhere; the online game operators are thus continuously playing cat and mouse with the cheaters. The forms of multiplayer game cheating all the same continue to thrive and gain new innovations. In Cheating the main forms of these practices are divided in four categories: taking advantage of game glitches, taking advantage of people, taking advantage of code, and taking advantage of third-party systems (p. 113).

There are plenty of interesting historical and contemporary examples about the human ingenuity in the case studies that are reported in Mia Consalvo’s book. Gaming obviously has the potential to bring multiple sides of human nature into light, and in a manner that makes the research of games and playing interesting also to those working in other fields of science and scholarship. Yet, perhaps the most interesting discussions are those, which Consalvo does not provide definitive answers for. Is cheating a particular kind activity that some players sometimes decide to perform, or is cheating producing cheater identity? (p. 127-128.) How ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ are being produced in game culture – and in culture and society more generally? (p. 188.) There are several discussions Cheating implicitly or explicitly links to in this regard; for example, the debates about ‘magic circle’ or the role of ‘negotiable consequences’ in games and play, on one hand, and the discussions about the ‘ethics of game design’ or the ethical relationships between online and offline actions and identities. The academic interest on cheating, grief play and related themes also continues strong. Mia Consalvo’s book appears as a recurrent reference in these and other discussions, giving already some proof of the lasting value this contribution has provided to the research field.(source: gamestudies)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号