研究称玩家融入感来自游戏本身交互性 与用户界面无涉

游戏邦注:本文原作者是卑尔根大学高级讲师Jørgensen,他研究了玩家对HUD的反应,并通过本文讨论保留故事情节或者游戏设置对玩家的重要性。

在最近几年,我们已经目睹设计师正在用不同的方式将用户界面融入游戏环境。经常提到的例子就是《死亡空间》高明的整合手法,该游戏将人物健康条替换成一条顺着人物脊柱的管道;而在《银河战士》的HUD中,由于其人物的脸型塑造,健康条仿佛是人物头盔上的一部分。

伴随着这股趋势,开发者群体广泛存在着关于透明化用户界面是否合乎人心的争论。

Greg Wilson在2006年争辩道,标准的HUD界面设计法阻碍了玩家融入游戏世界,这种既高深莫测又具有干扰性的技术功能只会吓退潜在新用户。

而Luca Breda却另有看法,他认为Greg Wilson的说法有误,因为完全没有用户界面,会将玩家置于与游戏相关信息绝缘的茫然境地。他相信HUD并不会损害用户黏性,反而会提供使用户更加融入游戏世界的信息。

这两个极端之间还夹着一个中间派。这个中间派的观点是,游戏用户界面的设计目的应该是把必要信息以清楚而一致的方式传达给玩家;同时要使用户界面美观、赏心悦目,与游戏环境融为一体,但无论如何这种设计都不能缺少必要信息。

Erik Fagerholt和Magnus Lorentzon在他们关于FPS(第一人称射击游戏)界面设计的硕士论文里采纳了这种方法。顺着这条思路,迷你化用户界面可能是一个理想的方法,但这并不能表明完全透明化处理用户界面就非常可行。

这两种观点在游戏开发者、游戏专业学生、游戏界记者等专业人士中都有不少拥趸。尽管开发商也许可以通过对目标玩家的测试得出自己的结论,但目前仍没有足够的资料可提供佐证。Jørgensen以四种类型的游戏(《暗黑破坏神2》、《模拟人生2》、《孤岛危机》、《命令与征服3:泰伯利亚战争》)为核心,研究了22名玩家对相关游戏用户界面的态度。

研究发现,无论用户界面是否是以覆盖面,或者不可见或者自然环境的一部分出现,只要它在适当的时候提供了必要信息,大部分玩家就能接受游戏用户界面。虽然多数玩家的态度是这样的,但还是有一些人对用户界面的存在持有异议。

研究过程及结果

这是一项定性研究,其目的是了解玩家对游戏用户界面的总体态度。在玩家体验其中一款游戏时Jørgensen就站在一旁观察玩家的行动,并通过随后的交谈了解并记录他们对游戏用户界面的相关看法。接受采访的五人讨论了四个游戏的截图,这四个游戏他们都玩过了。

Jørgensen根据人气、多样性和技术及时间限定,挑选了这四款PC游戏作为研究工具,并通过网上论坛、游戏社区和贴在游戏店里的海报招到了这些参加测试的玩家。

在研究过程中,玩家自由讨论除了选定的游戏之外的其他游戏。他们另外列举了几款带有不同功能用户界面的游戏。这意味着这项研究并非仅局限于之前所提到的游戏,但选定的游戏仍是主要讨论重点。

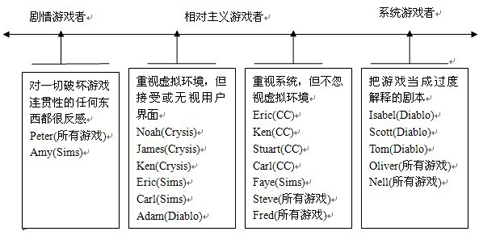

根据玩家对游戏界面及其与游戏环境融合的不同态度,Jørgensen归纳了下面这幅图以示说明。当然,为了尽可能清楚地展示资料,图片已做简化处理。下图展示的是各个玩家在访问中表现出的一般态度。

不同游戏风格的不同惯例

当然,游戏界面的接受程度与个人的偏好和游戏类型有关。一些类型的游戏允许玩家把HUD当成故事情节的一部分,是客观存在于游戏环境中的物体。

未来游戏和科幻主题游戏往往允许玩家将HUD当成人物在科技发达的世界能够看到的东西,第一人称视角的游戏特别擅长这种表现手法。《孤岛危机》就将HUD当成人物的高科技纳米装甲的组成部分。

然而,在其他类型的游戏里,玩家的定位及与游戏的互动一点也不逼真,在这种情况下,人们就可能很难将用户界面组件解释成虚拟环境的一部分。

上下视角的游戏,例如战略类和摸拟类游戏就不能这么解释游戏用户界面。在《模拟人生2》中,大部分玩家把用户界面组件当成只为玩家提供信息的功能,而且不是游戏人物能感觉到的东西。

一个有趣的发现是,游戏对玩家的定位会影响玩家对用户界面的解释。《命令与征服3:泰伯利亚战争》在过场动画中,明确地将玩家定位为指挥官。

在过场动画里NPC(游戏中的非玩家角色)直接对着镜头说话,告诉玩家下一个任务的信息。通过这种技术,游戏让玩家身如其境。

因为在《命令与征服3:泰伯利亚战争》里玩家角色被定位了,所以就好像这是一款第一人称视角的游戏,导致许多玩家认为覆盖式的用户界面显示在军事中心里的一台电脑屏幕上,从而使其成为虚拟环境的一部分。

在这种情况下,用户界面让玩家更加融入虚拟游戏世界,而不是干扰、阻断玩家对游戏的融入感。由此可以看出,设计者如何展示游戏用户界面,对界面的解读来说非常重要。

如果再看前面的图表,可以发现在《暗黑破坏神2》和《命令与征服3:泰伯利亚战争》中,玩家往往重视系统多于虚拟环境,而《模拟人生2》和《孤岛危机》中,玩家又重视虚拟环境多过系统。这意味着《模拟人生2》和《孤岛危机》的玩家更偏好那种可以理解为虚拟环境组成部分的用户界面,而《暗黑破坏神2》和《命令与征服3:泰伯利亚战争》的玩家则不那么看重这一点。

三种类型玩家的偏好

虽然许多游戏完全不解释用户界面,但也好像也没有让大部分玩家受到困扰。它们或许认为任何说明用户界面的方式,都是将界面解读为虚拟环境的一部分,同时也是华丽地展示界面的方法,但玩家是否完全接纳这种用户界面并不十分重要。

Jørgensen根据玩家对用户界面的理解和接受程度将其分为三类。这些类别说明三种不同的态度,开发者在设计游戏时务必考虑到这三种玩家的态度。这些玩家类型即上图所示的玩家对用户界面的态度,而作者要强调的是,用户界面的存在并不会破坏玩家对游戏的融入感和参与感。

剧情游戏者。他们认为游戏的情节和虚拟世界是电子游戏最主要的部分,同时希望游戏世界看起来、听起来都像展示在电影里的虚幻世界一样。他们对所有打断超脱的幻想世界的设置都没有好感。他们想融入游戏世界,却发现所有用户界面组件都是在破坏玩家对幻想世界的信仰。

“Peter”最能代表剧情游戏者的看法。他强烈支持游戏是叙述故事的虚拟媒介这一观点,对他而言,故事情节是增强游戏体验的一个重要功能。

他希望系统信息能与游戏世界相结合,成为虚拟环境的一部分。他声称第一人称射击游戏是“目前最贴近虚拟现实的游戏”,他欣赏这种游戏不会干扰玩家的设置,盛赞这类游戏将用户界面天衣无缝地融入游戏世界的特点:

它的用户界面没有干扰性。在第一人称(视角)游戏中,视觉焦点就是你所看到的。如果你射倒一个怪物时,怪物头上冒出得分,那种在游戏中身临其境的感觉立马烟消云散。

“Peter”不喜欢系统信息在游戏环境中出现,他觉得这类信息之所以不受欢迎是因为它们会破坏人们在虚拟世界的融入感。从这一点上看,他是Greg Wilson所称的用户界面只会影响玩家对游戏的融入感这一观点的支持者。

系统主义游戏者。他们把游戏看成是一个规则系统,认为理解系统是最主要也是最有趣的游戏活动。他们把虚拟环境当成游戏系统的覆盖面,而故事情节基本上只是个多余的配角,只是为了更好地展示游戏系统。毫无疑问,他们愿意接受用户界面,因为用户界面提供了控制和理解系统的必要信息。

“Isabel”代表的是系统主义者的观点。她在研究过程中玩了《暗黑破坏神2》这款她非常喜欢的游戏。她喜欢这款游戏很大程度上是因为它对虚拟环境和故事通俗易懂的处理。她并不关心在虚拟世界中的融入感,但却很有兴趣获得精良的装备和炫酷的技能。她称自己在玩其他游戏时也有相同的感觉,所以没有必要把用户界面解读为虚拟世界的一部分。她特意强调,她没有把游戏当成虚拟世界,这与游戏的场景没什么关系:

我不像其他人那么深地融入游戏。即使这是玩游戏的标准,我也并不关心。我就像玩《超级马里奥》那样玩游戏,所以用户界面设置在哪里没什么关系。

“Isabel”接受所有用户界面设置,只要它能让系统传达信息给她就成,她不在乎用户界面是覆盖式的功能设置还是人物头顶上的增益图标。

当谈论到游戏环境的真实度或可信度,她觉得把游戏环境当成玩家应该融入或信任的另一个世界,是很可笑的行为。

她大笑表示,“在这个游戏世界中,你可以把定义任何自己想要的东西,但这些东西本身并不可靠。”

相对主义游戏者。他们的观点介于剧情游戏者和系统主义游戏者之间,既欣赏虚拟图层也看好游戏系统菜单。他们认为整合用户界面或者虚拟化用户界面是个高明的解决办法,但也接受某些信息可能很难融入游戏中的现实。

只要界面能提供必要信息,相对主义游戏者就能接受覆盖式或者其他形式的用户界面的存在。不过相对主义游戏者也认为如果游戏用户界面提供了过多功能,也会对玩家造成干扰。在他们看来,游戏环境可以嵌入一些用户界面功能,而在影视环境中,这种设置完全不可能存在。

“Eric”在研究过程中体验了《孤岛危机》和《命令与征服3:泰伯利亚战争》。他强调电影和游戏环境之间的不同,解释了为何有必要理解用户界面与玩家之间交流:

无论一个游戏多么像电影,玩家自己做出发布命令和移动物品等命令后,他们都会需要系统反馈接下来会发生什么情况。

在这份调查研究中,大部分玩家代表的是相对主义游戏者,这一点并不令人意外。他们认为对作为一种媒介类型,用户界面已成为电子游戏的必要工具,这一点已经成为惯例,而这也是游戏世界的普遍运行方式。在大多情况下他们并不会质疑用户界面的存在问题,除非别人非要他们回答不可。

在游戏条件下,用户界面功能提供的信息增加了游戏的易玩性,从而增强了玩家的游戏融入感。然而,一旦一个功能无法实现它的目的和作用,它就会变得很烦人,同时可能毁掉玩家在游戏中的融入。

必要性是相对主义游戏者的重要说法。尽管将所有用户界面功能全部展示于虚拟游戏环境中可能是个好方法,但还是有许多游戏系统功能无法呈现于用户界面。以《魔兽世界》为例, “I cannot cast that yet”和“Not enough rage”这类口头语言的出现,会成为干扰剧情游戏者的影响因素,因为他们认为人物把这些话脱口而出很不合理。但是,相对主义游戏者却认为,这完全可以接受。

尽管用户界面是一种有时会产生干扰性的必需品,但相对主义游戏者没有特别排斥覆盖式用户界面。相反地,他们已经习惯了这些用户界面,也把它们当成了媒介的一种惯例。

他们知道这是电子游戏的一种交流方式,用户界面已经成为媒体的固定功能。就如同电影的剪辑和蒙太奇,用户界面并非技术缺陷,而是设计者可发挥创造力的一种优势。

“Oliver”对游戏用户界面与卡通画进行了比较:

像卡通,对么?我们之所以接受对话泡泡的存在就是因为卡通画就是这样子的。

与其他媒介一样,游戏也有自己的惯例。尽管剧情游戏者将影视故事叙述手法当成电子游戏的样板,但系统主义游戏者却认为规则系统的作用大于虚拟环境和游戏机制,并且与这两者没有相互作用;相对主义游戏者却高度理解作为独特媒介类型的电子游戏如何传达信息。

上文的图片也显示出,相对主义游戏者之间的观点也不尽相同。一些人强调系统的重要性,虚拟环境只是附加物等等,这就倾向于系统主义游戏者的观点了;还有一些人认为连贯的虚拟环境是最理想的,用户界面必须对它妥协,这就倾向于剧情游戏者的观点了。

融入感来自游戏交互性

本研究的结论之一是,游戏世界的运转并不像传统的虚拟世界(指电影、小说这类)。这是因为游戏世界是互动的,而电影和文学世界并不存在这种交互性。游戏世界是针对特定玩法而设计的,玩家对游戏环境有其他期待,这不同于玩家对电影环境的期待。

媒介学者J. David Bolter和 Richard Grusin已经在1999年时提出观点认为,数字媒介是技术恋物癖,同时试图掩饰自己的中介。他们可能是对的,至少电子游戏是这样的。尽管有许多游戏都试图通过在虚拟环境中添加用户界面功能来掩盖自己,但我们还是看到了,这其实无助于捕获玩家的注意力和融入感。玩家反而把用户界面当成司空见惯的东西了。根据游戏设计师Matt Weise的说法,玩家这么容易接受用户界面的原因是,电子游戏当中不存在第四堵墙。用戏剧隐喻来形容这堵无形的墙,就是说这堵墙把观众从舞台上的世界隔离了。Matt Weise强调,玩家的互动参与导致第四堵墙遁于无形之中,这一点在电子游戏中表现得非常明显,这也导致玩家带着自反意识来玩游戏。这个理论也适用于解释为何用户界面会被当成电子游戏的一个惯例。(游戏邦注:第四堵墙其实就相当于“自反意识”,带着自反意识做某事时,会不断强调自己只是在做这件事,就好比作家写作时,在作品里不断告诉读者作者自己是在写作一样)

新媒介学者Janet Murray争论道,像游戏这类互动或参与性的媒介,它的融入感来源与传统媒介是不同的,为其创造融入感的并非视听上的真实性,而是互动活动本身。

从这个角度看,能够在游戏环境中活动是融入感最重要的支撑。只要用户界面能够成为玩家最有效的工具,融入感就不会被覆盖面、HUD和图标的存在所影响。在这种意义上,一个美观实用的良好用户界面能帮助玩家融入游戏。

用户界面并不影响玩家融入感

实际上,这意味着游戏用户界面设计者不必太担心覆盖式用户界面和可视组件与游戏环境不相融,然后玩家的参与感会被破坏的情况。然而,虽然大部分玩家往往被归类为相对主义游戏者,但设计者还是应该意识到,许多玩家既不是系统主义游戏者也非剧情主义游戏者,应该兼顾这部分玩家的需求。

同时这意味着用户界面设计者虽然不必担心用户界面功能能否与虚拟环境融合,但也需要讲究用户界面设计,使它有适合的风格。同时,设计者们要牢记于心,用户界面显然为玩家提供了必要信息。如果游戏设置信息没有直接表达出来,新玩家可能会觉得疑惑和无法控制游戏;用户界面在吸引新玩家这一点上显得至关重要。

当然,评估用户界面应该如何在游戏中体现,还必须考虑到游戏类型和特殊的游戏机制。在现代第一人称射击游戏中,把HUD整合为游戏人物服装的一部分可能比较合适;而在大型多人网游中,如在公会活动和PvP(玩家与玩家PK)情况下,因为查看许多同步进程至关重要,所以大量的覆盖式信息界面可能更合适。

只要设计者清楚明白地遵循游戏系统的信息传达原则,就可以将用户界面以不同的方式补充到游戏中,并使其在虚拟环境和游戏系统之间游刃有余。游戏设计者应该好好利用用户界面,不必担心用户界面可能会破坏玩家融入感的情况。游戏设计者应该把任何程度的用户界面融合度当成是加强了游戏的易用性;用户界面可以为玩家与游戏世界的互动提供更多的选择,而不是消除玩家的融入感。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,转载请注明来源:游戏邦)

The User Interface Continuum: A Study Of Player Preference

[University of Bergen senior lecturer Jørgensen studies gamers' responses to HUDs, and whether or not the need to preserve the fiction or the gameplay is paramount to players -- and delivers the results of this investigation, along with suggestions.]

During the last several years we have seen designers being drawn towards integrating the user interface into the game environment in different ways.

Game Advertising Online

Examples that are often mentioned as particularly elegant ways of doing this are Dead Space, where the health bar is substituted by a tube running down the spine of the avatar, and Meteroid Prime, where the HUD gives the impression of being part of the avatar’s helmet due to shaping and the reflection of the avatar’s face.

Along with this trend, there has also been a debate in the developer community about whether or not this ideal of transparency is desirable.

Greg Wilson argued strongly in 2006 that the standard HUD approach to interface design hinders players from immersing into the game world, and that it is an intimidating and intrusive technical feature that turns potential new players off.

On the other side of the fence we find Luca Breda who argues that the above approach has pitfalls, since a total lack of interface leaves the player without any information relevant for play. Instead he believes that HUDs don’t harm the players’ involvement in the game, but on the contrary provide information that helps them become more closely attached to the game world.

In between these extremes there is a middle ground. This middle ground represents the argument that the goal of in-game user interface design should be to communicate all necessary information in a clear and consistent manner, while also making it elegant, aesthetically pleasing, and integrated into the game environment whenever this may be done without losing necessary information.

This is the approach taken by Erik Fagerholt and Magnus Lorentzon in their master thesis [PDF] on the design of FPS interfaces. Following from this line of thought, minimizing the interface may be an ideal, but this doesn’t indicate that complete transparency is desirable.

The arguments supporting either view come from experts such as game developers, game students, or game journalists. Although the developers may take their conclusions from testing with target group players, there are no references that indicate this. With point of departure in four PC games belonging to different genres (Diablo II, The Sims 2, Crysis and Command & Conquer 3: Tiberium Wars), I have in my research done 22 studies of players regarding their attitudes concerning game user interfaces.

In my study, the general tendency was that players accept the user interface regardless of whether it are present as overlays or made invisible or parts of the natural environment as long as it provides necessary information at the appropriate moments. However, although this is the attitude of most of the players in my study, there were those with different attitudes towards the presence of the user interface.

The Study

The study was a qualitative study where the aim was to understand players’ general attitudes towards game user interfaces. In the study I observed players while they were playing one of the games in question, followed by an interview where we discussed a recording of their gameplay with special attention towards the user interface. A group of five was subjected to a group interview where they discussed screenshots from all the four games, with which they all had previous experience.

The games were selected based on popularity and diversity and technological and time-related constraints only allowed me to use PC games for the particular study. The players were recruited through the use of web forums of game communities and posters at game stores.

During the study, the players were free to also talk about games other than the ones selected, and they provided several examples of games where they found the user interface to be interesting for different reasons. This means that the study is not based on the above mentioned games only, but that these titles were the primary, but not exclusive, focus of the conversation.

The conclusions were based on careful categorization and analysis of the interviews, and for the sake of illustration I have in the figure below grouped the players according to the different attitudes they presented towards game interfaces and the integration into the game environment. Of course, this is a simplification for the sake of presenting the data as clearly as possible, and the illustration shows the general attitude that the individual players were presenting in the interview.

Different Genres, Different Conventions

Of course, the degree of interface acceptance is a matter of personal preferences as well as the conventions of user interface design related to a certain game genre. Some genres allow the players to interpret the HUD as part of the fiction, and therefore as something that exists objectively in the game environment.

Futuristic or science fiction-themed games typically allow the player to interpret the HUD as something that the avatar sees due to technological enhancements, and first-person view games are particularly good at presenting this interpretation as likely. Crysis, for instance, explains the HUD as a part of the avatar’s technologically advanced nanosuit.

However, in other genres the player’s positioning or interaction with the game is not set up as “realistic” at all, and in such cases it may be hard to explain interface elements as part of the fiction.

Top-down perspective games such as strategy and simulation games are typical examples of this. In The Sims 2, most players interpret interface elements as information meant for the player only, and it is not seen as something that the sim figures are aware of.

An interesting finding was that the way the game addresses the player affects the interpretation of the interface. Command and Conquer 3: Tiberium Wars, for instance, addresses the player specifically as commander during the cutscenes.

Here NPCs provide the player with information on the next mission by speaking directly into the camera. By using this technique, the game provides the impression that the player is a character in the fiction.

Being addressed as if the game was played from the first-person perspective, many players were inspired to see the overlay interface as belonging to a computer screen in a military centre, and therefore as part of the fiction.

In this situation, the interface supports the sense of involvement and immersion into the fiction instead of being intrusive and alien to the situation. Here we see that how the designers have chosen to explain the interface often is important for how it is interpreted.

If we take a look at the figure on page 1, we see that the players had a tendency to emphasise the system over the fiction in connection with Diablo and Command & Conquer 3, while fiction was emphasized over the system in Crysis and The Sims 2. The means that there was a tendency for players of Crysis and The Sims 2 to prefer a user interface that could be explained as part of the fictional environment, while the Diablo and Command & Conquer players tended to see this as less important.

Player Preferences: Three Archetypes

However, very many games don’t try to explain the user interface at all, and this doesn’t seem to bother most players. While they see any way of explaining the interface as a part of the fiction as an elegant way of presenting the interface, it is not necessary to make the players accept it.

In the following I want to separate three groups of players according to how they interpret and accept the user interface. These groups are archetypes that illustrate three different attitudes that game user interface designers must consider when designing game interfaces. The archetypes correspond to the attitudes to user interfaces presented in the illustration above, and emphasize that the presence of the user interface in itself doesn’t ruin the sense of immersion and involvement in a game.

The Fictionalists. They see the game’s story and fictional world as the most central aspects of video games, and want the game worlds to look and sound exactly like the fictional worlds presented in film. They are negative to all features that disturb the illusion of a coherent world existing separately from our own. They want to immerse into the story world and find all interface elements to be disturbing for the ability to suspend disbelief.

“Peter” represents the Fictionalist view, and his attitude colors his interpretation of all four games that he is discussing in the focus group interview session that he was part of. He is a strong supporter of games as a fictional medium of storytelling, and for him this is a feature that heightens the play experience.

He wants system information to be integrated into the gameworld and made part of the fiction. He claims that first-person shooters are the “closest you get to virtual reality these days” and celebrates their non-intrusive inclusion of the player, as well as the genre’s tendency to integrate the user interface seamlessly into the world:

It’s so nonintrusive. The focus is always on first-person [perspective], it’s you who’re looking out. If a score appeared above the monsters’ heads when you shot them down [...], then the immersion would disappear immediately.

“Peter” doesn’t want system information to reveal itself in the game environment, and argues that such information is unwelcome as it ruins the sense of immersion into the game fiction. Using this argument, he is supportive of Greg Wilson’s view that the interface only can lessen immersion.

The Systemists. They see the game as a formal system of rules and regard understanding the system as the most central and interesting game activity. They see the fictional environment as an overlay to the game system, and find the fiction to be present only as a supportive feature that is mainly unnecessary and only there to represent the system beyond. They accept the interface without question since it provides contact with the game system and presents information necessary for controlling and understanding the system.

“Isabel” is a representative of the Systemists. She played Diablo II in the study, a game that she enjoys quite a lot partly due to its superficial treatment of fiction and story. She doesn’t care about immersing into the fictional world, but is interested in getting good gear and cool abilities. She claims that she has the same attitude when playing other games as well, and doesn’t have any need for explaining the interface as part of the fictional world. She is consciously emphasizing that she doesn’t see the game as a fictional story world, and she sees the setting of a game as irrelevant:

I don’t immerse myself into these games as much as others perhaps do. Even though it’s a typical part of playing games, I don’t care so much about it. I play it just as if it were Super Mario, in a way. It’s not that important for me where it’s set.

“Isabel” accepts any user interface features as a way for the system to communicate information to her, regardless of whether they are added as overlay features or buff icons above the avatar’s head.

When discussing the degree of realism or trustworthiness of the game environment, she finds it absurd to see the game environment as any kind of environment that one is supposed to immerse in or believe in as if it were just another story world.

She laughs out loud, then states that “in this world you can define whatever you want there to be, it’s not like things are very trustworthy in themselves.”

The Relativists. They are in the middle ground between the Fictionalist and the Systemist, and appreciate both the fictional and the game system layers. They see attempts at integrating the user interface or fictionalizing it as elegant solution, but accept that certain kinds of information may be hard to include.

The Relativists accept the presence of overlays and other interface features as long as they provide the necessary information, but find them disturbing if they are overused. The ability to provide appropriate information makes it acceptable to include features in the game environment that would not be appropriate in a cinematic environment.

“Eric” played both Crysis and Command & Conquer 3 in the study. He puts emphasis on the difference between cinematic and gamic environments to explain why clear interface communication is needed:

Regardless how cinematic a game is there needs to be… Since you make all these decisions yourself, issue commands and move things, you need to have some kind of feedback on what’s going on.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, most of the players in my study were representatives of the Relativist attitude. They explain the user interface as a necessary tool that has become conventional to video games as a media genre. They explain that this is the way game worlds work, and that they in most cases don’t question the presence of the interface unless being asked to reflect on it.

In a gaming situation, interface features provide information that eases gameplay and they are therefore enhancing more than hindering immersion. However, once a feature doesn’t serve its purpose and function anymore, the feature becomes annoying and risks ruining the sense of involvement in the game.

Necessity is therefore an important explanation for the Relativists. Although it may be more elegant to present all interface features as natural to the fictional game environment, there are many game system features that cannot be represented as such. For instance, verbal messages such as World of Warcraft’s “I cannot cast that yet” and “Not enough rage” would appear as a negative intrusion for the Fictionalists, as they would argue that it makes no sense that the avatar would say that out loud, but for the Relativists this is perfectly acceptable. In such cases, “James” argues,

[t]here is no other way they could have done it without also removing a great part of the game mechanics.

Although some otherwise intrusive uses of interface are included as necessities and not the most elegant solutions, the Relativists do not see overlays as necessary evils. On the contrary, they have become so accustomed to them that they have accepted them as conventions of the media genre.

They know that video games communicate in this manner, and that user interfaces have become a stylistic feature of the medium. Like the cuts and montages of cinema, the user interface is not seen as a technical shortcoming, but as a technique that may be used to the designer’s advantage. “Oliver” makes a clarifying comparison between game user interfaces and cartoons:

It’s like cartoons, right? [...] We accept the speech bubbles because that’s the way cartoons work.

Like other media, games have their own conventions that they relate to. Although the Fictionalists regard cinematic and televised storytelling as the template that they regard video games on the basis of, and the Systemists only sees the formal system beyond and not the interplay between fiction and game mechanics, the Relativists have a high degree of understanding and literacy of how video games communicate as a unique media genre.

The figure shows that there is also variation between Relativists. Some lean towards the Systemists by emphasizing that the system is what matters and that the fiction only is an addition that that, while others lean towards the Fictionalists by seeing a coherent fictional environment as the ideal that the user interface should adapt to.

What Does This Mean?

Not surprisingly, one of the conclusions from the study is that game worlds don’t operate in the same way as traditional fictional worlds. This is related to the fact that game worlds are interactive, while the worlds of film and literature not being interactive. Game worlds are designed for a specific gameplay and the players therefore have other expectancies from the game environment than they have from the environments represented in films. But this is only part of the explanation.

The media scholars J. David Bolter and Richard Grusin argued already in 1999 that digital media genres, among them video games, are technology fetishist at the same time as they try to mask their own mediation. They may be right, at least when it comes to video games. Although there are games that try to mask their own mediation by implementing user interface features into the fictional environment, we have seen that this is not necessary for capturing the players’ involvement and sense of immersion. Instead the players accept the user interface as conventional.

The reason why accepting the interface is so easy for the players, is according to game designer Matt Weise due to the fact that there is no fourth wall in video games. Using a theatre metaphor that describes the invisible wall that separates the audience from the world on stage,

Weise emphasizes that the player’s interactive involvement makes the absence of the fourth wall very obvious in video games, and that this allows games to play with self-reflexivity and the very mediation of games. This theory is also appropriate for explaining why the user interface is accepted as a convention.

New media scholars such as Janet Murray have argued that in interactive or participatory media such as games, immersion is empowered by something different from traditional media. It is not the audiovisual realism that creates immersion, but instead it is the interactivity itself.

From this perspective, having the power to act within the game environment is the most important support for immersion. As long as the user interface is able to provide the player with the most effective tools for doing this, immersion is not compromised by overlays, HUDs and the presence of icons. In this sense a good interface which is both elegant and functional will help the player immerse.

But What Does It Mean For Game User Interface Design?

In practice, this means that game user interface designers should not be too worried about ruining the players’ sense of involvement when using overlay interfaces and visual elements that don’t fit into the fictional environment. However, although most players out there tend to fall into the category of the Relativists, designers should also be aware that there are many out there who are either Systemists or Fictionalists. These groups should also be catered for.

In practice this means that user interface designers should not worry if interface features are not integrated as natural to the fictional environment, but also strive towards making the user interface as elegant as possible to make it stylistically appropriate. At the same time they must keep in mind that the user interface provides necessary information as clearly as possible. This is particularly important for appealing to novice users that may be confused and feel lack of control if gameplay information is not communicated in a direct manner.

Of course, in making evaluations of how the user interface should be represented in a game, the genre in question and the specific game mechanics must be considered. While it may be appropriate to integrate the HUD as a natural part of the avatar’s suit in a modern FPS, it is probably better to have substantial overlay information in an MMO, in which the monitoring of a lot of simultaneous processes are crucial, for instance in raids and PvP situations.

The user interface may be implemented in a range of different ways, and as long as the designer follows principles of communicating the game system in a clear and understandable manner, one is free to play with the border between fiction and game system. The designers should utilize the interface for what it is worth and not be afraid that it might disrupt the sense of immersion. One should see any degree of integration of the interface as an enhancement of usability; something that provides the player with more options for interaction in the gameworld, and not something that removes immersion.(source:gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号