Ian Bogost解析抽象益智游戏的数量崇高现象

游戏邦注:本文作者是游戏设计者兼作家伊恩·博格斯特(Ian Bogost),他通过哲学角度对《Drop 7》、《Orbital》这两款游戏的数量崇高现象进行了解读。

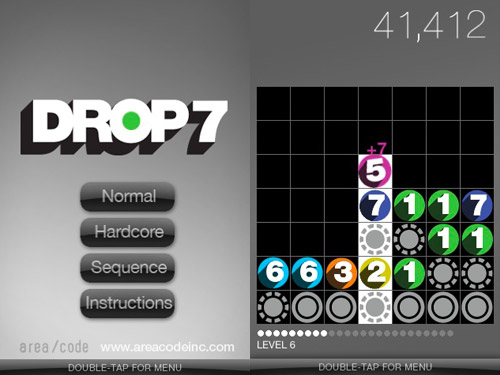

我想谈谈两款很棒的手机益智游戏:Area/Code公司推出的的《Drop7》以及Bitforge公司的《Orbital》。但这里有个问题:抽象的益智游戏的概念不太好理解,至于什么样的益智类游戏是好游戏,就更难解释得清楚了。

当然,我们可以讨论益智游戏的属性,或者美学感受,或是界面的问题,也可以就其新颖性和创造性展开探讨,甚至可以谈谈这些游戏玩起来多么令人上瘾。但这些看起来都只是对《Drop7》和《Orbital》的一些肤浅的认识。

我们能不能从《生化奇兵》(BioShock)、《吃豆人》(Pac-Man)和《模拟城市》(SimCity)的角度出发来讨论这些益智游戏?这些游戏不论是故事框架,特征描述还是虚拟性,或多或少都有些类似。每一款游戏都有具体的主题,并通过游戏规则和环境体现出来。

的确,我们很难确切地讨论这类抽象游戏究竟为何物,因为他们本来就没有实体。而那些带有更多可辨识主题的游戏,倒是能为大家理解游戏主题提供些切入点。

以象棋为例,很显然象棋的发明灵感来自军事斗争,不只是因为历史渊源和虏获机制,还因为它的命名和雕刻的图案。当骑士逮到一个兵,就很容易就联系到战斗姿态。

围棋则更难以定义,法国哲学家吉尔·德勒兹(Gilles Deleuze)和菲利克斯·瓜达希(Félix Guattari)的形容是:“围棋(与象棋相比较),只是一堆球片,圆盘,简单的逻辑单元,只有一个无名、集体的第三方功能:走一步围棋,移动的棋子可以代表一个男人,也可能是一个女人,一只虱子,一头大象。”

即使可以将一颗围棋子想象成一名战士、一头大象或者一家沃尔玛,它的游戏规则从根本上还是服务于抢夺地盘的目标:占得多的一方得胜。

拼图游戏就更麻烦了。一些逻辑类和数学类的益智游戏,都有像Three Utilities Puzzle(游戏邦注:水气电难题) 这样明确的主题或者故事背景。但像九宫格(sudoku)等其他游戏却并不满足这一点,大部分益智游戏往往只有概念上的形式,只有偶尔才会体现出具体的主题。

拼图的表面可能印有风景或者汉堡的图案,但这些东西和难题本身没有什么关系,它们只是为服务于游戏任务而存在。一些手动操作的益智游戏,如七巧板等也与此类似。

而像跳珠消除和魔术方块等其他游戏则完全是抽象的,与现实世界的人和活动毫不相干。

关于抽象游戏的评论

众所周知,电子游戏传承了益智游戏的核心机制。采用了逻辑谜题原理的解密冒险类游戏,通常会让玩家操作物品开启门锁;还有大量的游戏改编自传统的抽象棋类游戏。但对现代抽象游戏影响最大的还是手动操作型的益智游戏,主要原因在于:容易进行空间转换。电子游戏最擅长物体的空间操作。

当我们试着以严谨的态度来讨论抽象益智游戏时,又会发现新的问题。我们很难对益智游戏作出贴切的解释,因为它们不像小说、电影或者油画那样可以表达各自的蕴义。举个例子,在Cracker Barrel连锁餐厅的桌上玩跳珠消除游戏,并不需要参阅像宗教经文一样详细的游戏指南。

理解抽像艺术的一个方法是把它看成一种隐喻或者寓言。在一些情况下,我们看作品的标题就能理解它的含义。马赛尔·杜尚的立体派油画《下楼梯的裸女》直接展现了动态人体的多重视角、动作叠加的艺术形式。同样的,皮特·蒙德里安著名的油画《百老汇爵士乐》反映了纽约城喧闹的景象。

在其他情况下,多数作品本身并不会自我解释其中蕴义,关键还得看欣赏者自己的理解。再举个例子,蒙德里安的油画《Composition with Yellow Patch》在名称和画布上也并没有任何解释说明,只能看欣赏者的见仁见智。

游戏很少通过名称传达具体含义,很大程度上是因为游戏没有油画那种有强大的历史纽带。但只要我们真想明白,就可以凭自己的理解能力读懂其内在本质。

关于抽象益智游戏的理解,最具代表性的例子可能是珍妮·玛瑞(Janet Murray)对《俄罗斯方块》的解读。她在1997年出版的《全息平台上的哈姆雷特》一书中称该游戏是:“为超负荷生活的美国人打造的完美游戏。”四格方块落下来,就像美国人赶着要完成的任务,要阅读的电邮,参加的会议等等。玩家要迅速作出反应,不然砖块的全面袭击很快就会让他们无法招架。可是游戏暂停、存档、玩够了之后,整个过程又开始循环了。玩家没有逃避的选择,只能想法挽回必然的失败。

评论家Markku Eskelinen争锋相对地指出玛瑞的观点很荒谬,他认为玛瑞并没有弄懂游戏本身的内容,而只是把自己的观点强加于游戏之上,结果导致大家谁也没搞清《俄罗斯方块》何以成为一款游戏。

Eskelinen还表示,把苏联游戏解读为美国人工作伦理的隐寓实在是很奇怪,并指出“这比把象棋解释为最贴近美国人的游戏这种说法更不靠谱,至少象棋反映出美国社会的黑白阵营总在进行阶级斗争,性别也不平等,生病的人也没有医疗保障的现象。”

尽管如此,玛瑞的解释还是完全合乎情理的。从文学和艺术评论的角度来说,她提出了一些本质的东西:证据出自游戏作品本身。游戏诞生于铁幕背景之下的事实并不是问题,它完全可以在自身的创作环境之外,获得出乎意料的新解释(游戏邦注:法国哲学家雅克·德里达称之为“散播”概念)。没人可以告诉你一件作品的“真正意义”,除非你能提出示文本资料,让大家相信你的解释有据可考。

玛瑞和Eskelinen关于抽象益智游戏的争论在于,一方想从故事角度对游戏进行解释,而另一方却只想让游戏以自身形式来体现。这两者其实是相互依存的,少了对方都不正确。所以有可能是这种情况:抽象游戏的“意义”介于它的机制和动态之间,而非仅偏向于其中一者。

数量的崇高

18世纪的康德在一本关于美学的书中,辨析了美丽和崇高的定义。他认为美丽是对事物的一种无逻辑的、主观的美学判断,而崇高则是因想像力和理性而形成的一种状态。

康德指出,数量的崇高是一种无穷无尽的或者广阔无边的感觉,这是因数量无限大而产生的感觉。例如,看金字塔这种建筑时就会产生这种感觉,因为金字塔太大,不可能一眼就看尽。

动态的崇高指的是一种被征服的感觉。这种感觉通常来自自然事物,例如直面海上悬崖,巨大的雷云。数量的崇高感因巨大而生,动态的崇高感则生于敬畏。

我认为《Drop7》和《Orbital》的意义与崇高颇有关联,尤其是数量的崇高。

在《Drop7》游戏中有两种球:无数字的灰球和带数字的彩球(数字是从1到7)。彩色球落到7*7的方格里,要么落在方格底部,要么叠在方格中的其他球上。如果这个彩色球上的数字与横排或纵列上的其他球的数量相同(与其他球上的数字无关),这个彩色球就会消失。

灰色球在显示出数字前不会自己消失。只有在邻近的彩色球爆炸后才发生变化(炸一次变碎,再炸一次变彩色球)。每消一个球,就得到相应的分值,并且相应排列的球也消失。

玩《Drop7》游戏多数时候要看准时机。进入下一关时,最底层加入一层灰色球,现家只能随机摆放球。在一些刚好的情况下,可能出现合适的数字,玩家就可以直接按设想好的方式排列;若不巧出现的是一些不合适的数字,玩家只能另谋出路。此外,灰球出现后,所带的数字还是未知的,直到旁边的球炸到它两次,它才会显示出来。

同时,这些组合需要玩家在每一关都重新估计。灰球可以看成是未知数,但这并不明智 。聪明的做法是大胆假设隐藏数字的最差可能性,并且采取相应的策略。

然而即使那样,每一关也还是要根据上一关的结果和当下的情况来重新评估大局。象棋和围棋中每一步的后果是自然而然产生的, 但《Drop7》中每一步都可能对下一步造成深远的影响,这一点即使是菜鸟级玩家也看得出来。

在《Drop7》游戏过程中,玩家得到一组渐渐改变的不确定因素,然后用计划中的这一步来应对之后还未确定的一步。每一步移动都存在无数可能性,够玩家计算好一阵了,这种计算一直进行到新出现的随机数字打断为止。玩家就是从这种计算中了解到这款游戏的数量的崇高。

玩家只能暂时性地掌握规律,因为每一个球落到固定位上都意味着消灭了之前存在的无数可能性。但这并不像象棋、围棋在棋盘上不断改变的动态分布,当之前未知的影响因素开始作用于当前的移动时, 《Drop7》当前的每一步操作也在影响下一步行动,如此环环相扣。

在《Orbital》游戏中,玩家在游戏界面底部用可旋转的炮台发射魔法球。这些魔法球因惯性在空间壁和其他魔法球之间弹跳,一旦停下来,魔法球就会变大,除非魔法球碰到空间壁或者其他魔法球。

玩家要做的就是用新发射的魔法球打旧的魔法球三次,使之爆炸(每个球上都会显示被击打的次数),并因此而赢得分数。但如果弹跳的魔法球下落超过玩家炮台上方的白线,游戏就会结束。由于游戏采用的是宇宙背景,运动中的魔法球就会形成引力场,改变后来魔法球的弹跳轨道。

与《Drop7》类似,魔法球的不断增加和聚集,它们的移动轨道不可确定,所以总会让玩家在游戏中吃尽苦头。魔法球会根据空间的摩擦力和引力,产生某种弹跳轨道,玩家的游戏策略与他们对这些轨道的预测密切相关。玩家可以尝试把一群魔法球集中到空间的角落,然后一次性消灭多个魔法球。

但是,每解决一个魔法球,都会改变游戏空间的一部分引力布局,使玩家刚形成的空间物理布局感消失。即使玩家赢了,也还是会产生方向迷失感,因为爆炸的魔法球又改变了局部引力。

《Drop7》游戏主要通过时机来实现数量的崇高:通过玩家的操作,在灰球层中显示随机数字。而《Orbital》就没有任何时机可言了,它的每一步操作都是可估测的。但是,千变万化的宇宙环境太过辽阔,使玩家没法为下一步做好打算,无论之前有没有计划周全,玩家都必须战胜游戏中的定时系统和物理学,有针对性地发射魔法球。

《Drop7》会慢慢筛出选项直到玩家彻底失败,但《Orbital》对操作失误可没那么宽容,它会把失误显示在屏幕上,即使玩家只是犯了最小的失误也不例外(游戏邦注:魔法球最轻微的摩擦也会留下一条细碎的线)。

《Drop7》和《Orbital》的体验过程简直是弦理论的实践版,是在评估无限未来的未知走向。无论玩家的表现如何,这些吸引人的游戏系统都会让他们体验到数量的无限,每一步都改变着他们的行动。

抽象游戏的隐喻

我们能不能说《Drop7》和《Orbital》“关于”什么东西?如果能,那是关于什么?现在有必要返回讨论玛瑞对《俄罗斯方块》的理解。

有人可能会发现《俄罗斯方块》也存在类似的数量的崇高。每降落的一个方块都会改变整个游戏的布局,玩家要玩下去就要调整布局,看时机决定哪块可以用来补全之前堆起来的方块。

但《Drop7》、《Orbital》与《俄罗斯方块》最重要的区别是:前面两者是回合制游戏,并不存在连续性。在《Drop7》和《Orbital》中,玩家有机会仔细考虑任务的艰巨性和数量崇高的条件,必须一直稳住当前状况以持续下一步。

当玛瑞把《俄罗斯方块》解读为关于永无止境的苦差事游戏时,她不是指游戏的数量崇高的动态,而是游戏操作的暂时动态。

办公室工作通常不具有类似《Drop7》和《Orbital》这两个游戏世界的崇高,而往往是对时间流逝的体验,是永不停息的过程,无论这个过程有没有前进都是如此。

在《俄罗斯方块》当中,用户的玩法会阻碍通向崇高的道路。但在《Drop7》和《Orbital》这里,玩家对崇高的思考和反应却被作用机制强化了。

例如,《Drop7》为玩家创造了面对未知——不只是未来(还没被落下的球),还有过去(已经暴露的灰色球上的数字)的恐慌和渺小的体验。这种体验就像像是一种个人选择。要不要捐助红十字会?要不要信仰伊斯兰教?要不要找个情妇?

的确,《Drop7》的表面和模式可完全不像是这么回事,但它与个人选择所带来的数量崇高的体验是相似的。

有人可能会认为,比起《Fable》或《生化奇兵》中的选择,《Drop7》更像是关于道德的选择。《Fable》或《生化奇兵》可以模拟出用户决定的动作,但就像《俄罗斯方块》那样,它们并不通过动态获得选择的主题。

《Orbital》可以看成是一款建立在这个主题之上,但面向不同方向的游戏。《Orbital》不存在时机因素,魔法球因炮台的轰击在空间中弹跳。就算玩家通晓宇宙物理力学的知识(魔法球在游戏宇宙主题背景中形成弹跳轨道)仍然不可能指望有朝一日可以在这种空间游戏中获胜。即使是骨灰级玩家也不行,这款游戏的全球最高分仍然低于200分。

结论

优秀的益智游戏对人们是很有帮助的。但如果通过内容的引人入胜,或者深度、高雅等判断标准来称之为优秀,那就是说抽象游戏只会对玩家产生冰冷生硬、形式上的作用。而崇高实际上是形式主义的对立面,是一种征服、巨大、丰富的感觉。

崇高帮助我们看到人类理性的极限,向我们展示了这个世界的动荡和巨大。这样的主题很显然还不能由几款方块、数字和图形游戏完全展示出来,也无法通过几款关于战争、牺牲和损失的游戏彻底体现。

益智游戏中的数量崇高应当会给我们游戏开发者和评论家更多思虑,我们经常把游戏和自己所熟悉的艺术形式,例如电影、油画和文学作品等相比较,评选出游戏中的杰作。但事实上,崇高无处不在,在建筑,在自然,在气候中,也许我们也能从中找到灵感来源。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,转载请注明来源:游戏邦)

Persuasive Games: Puzzling the Sublime

[Good puzzle games are often described as addictive, elegant or deep, but in reality they can elicit deeper feelings of overwhelm, vastness and abundance, says author and game designer Ian Bogost in his latest Gamasutra column.]

I want to discuss two excellent abstract puzzle games for the iPhone: Drop7 by Area/Code and Orbital by Bitforge. But there’s a problem: it’s hard to talk about abstract puzzle games, particularly about why certain examples deserve to be called excellent.

Sure, we can discuss their formal properties, or their sensory aesthetics, or their interfaces. We can talk about them in terms of novelty or innovation, and we can talk about them in terms of how compelling they feel to play. But such matters seem only to scratch the surface of works like Drop7 and Orbital.

Can we talk about such games the way we talk about, say, BioShock or Pac-Man or SimCity? All of those games offer aboutness of some kind, whether through narrative, characterization, or simulation. In each, there are concrete topics that find representation in the rules and environments.

Indeed, it’s hard to talk about abstract games precisely because they are not concrete. Those with more identifiably tangible themes offer some entry point for thematic interpretation.

Chess, for example, clearly draws inspiration from military conflict, not only because of its historical lineage and mechanics of capture, but also thanks to its named, carved pieces. When a knight takes a pawn, it’s easy to relate the gesture to combat.

Go is somewhat harder to characterize. As philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari wrote of the game, “Go pieces, in contrast [to chess], are pellets, disks, simple arithmetic units, and have only an anonymous, collective, or third-person function: ‘It’ makes a move. ‘It’ could be a man, a woman, a louse, an elephant.”

Even if one can imagine a go stone as a soldier or an elephant or a Walmart, the game is still fundamentally about territory: whoever captures more of it wins.

Puzzles create more trouble. Some logical and mathematical puzzles, like the Three Utilities Puzzle have clear subjects or storylines. Others, like sudoku, do not. Most often, puzzles are entirely conceptual in form, with concreteness a mere accident of presentation.

A jigsaw puzzle might have a landscape or a hamburger imprinted on its completed surface, but that subject bears no relation to the puzzle itself. It’s just a skin that facilitates the job of construction. The same is true of some manipulable puzzles, like tangrams.

Others, like peg solitaire and Rubik’s Cube are entirely abstract, with no clear relation to any sort of worldly being or action.

Abstract Game Criticism

As we know well, video games have frequently inherited from the tradition of puzzles. Text and graphical adventures make use of logical puzzles, often ones that require manipulating items to unlock doors. And we have plenty of adaptations of traditional abstract board games. But it’s really manipulable puzzles that have had the strongest influence on contemporary abstract games, and for good reason: spatial relations translate well. Video games are good at manipulating objects in space.

A problem arises when we try to talk about abstract puzzle games critically. The truth is, it’s hard to perform thoughtful criticism on puzzles, because they don’t carry meaning in the way novels or films or oil paintings do. The peg solitaire set on the table at Cracker Barrel does not function as a religious text, for example.

One approach to understanding abstract art is to treat them as metaphors or allegories. In some cases, the art helps us out by means of its title. Marcel Duchamp’s cubist painting “Nude Descending a Staircase” immediately reveals the multi-perspective, superimposed forms of a human form in motion. The same goes for Piet Mondrian’s famous final painting, “Broadway Boogie Woogie,” which reflects the bustle of New York City.

In other cases, no such help can be gleaned from the work itself, and viewers must seek their own interpretations. Such is the case with Mondrian’s “Composition with Yellow Patch,” for example, which offers no interpretive handle in its title or on its canvas.

Games rarely give much away through their titles, mostly because they don’t have a strong genealogical relationship with the history of painting. Still, our interpretive capacity makes it possible to read meaning in anything if we choose.

Perhaps the best-known representational interpretation of an abstract puzzle game addresses the best-known such game: Tetris. In her 1997 book Hamlet on the Holodeck, Janet Murray described Tetris as “the perfect enactment of the overtasked lives of Americans.” Tetriminoes fall, like tasks to be completed, emails to be read, meetings to be attended. One must act quickly or the onslaught will quickly overwhelm. But once checked, filed, or satisfied, the process just starts all over again. There is no escape, save inevitable defeat.

Critic Markku Eskelinen pugnaciously disputes Murray’s account as absurd: “Instead of studying the actual game Murray tries to interpret its supposed content, or better yet, project her favourite content on it; consequently we don’t learn anything of the features that make Tetris a game.”

Eskelinen points out the curiosity in reading a Soviet game as an allegory for the American work ethic, and offers that “It would be equally far beside the point if someone interpreted chess as a perfect American game because there’s a constant struggle between hierarchically organized white and black communities, genders are not equal, and there’s no health care for the stricken pieces.”

Yet, Murray’s interpretation is entirely reasonable. From the perspective of literary or art criticism, she offers something essential: evidence from the work itself. The fact that the game was made behind the Iron Curtain doesn’t matter; a work escapes the context of its creation and recombines with new interpretations in myriad unexpected ways (a concept the philosopher Jacques Derrida calls dissemination). Nobody can tell you what a work “really means,” provided you can mount textual evidence to show that your interpretation is sensical.

The problem with the Murray/Eskelinen approach to abstract puzzle games is that one wants the game to function only narratively, the other wants it to function only formally. Neither is exactly right without the other. The problem seems to be this: the “meaning” of an abstract puzzle game lies in a gap between its mechanics and its dynamics, rather than in one or the other.

The Mathematical Sublime

In his eighteenth century tome on aesthetics, the philosopher Immanuel Kant distinguishes between the beautiful and the sublime. He relates beauty to non-logical, subjective aesthetic judgments about the form of things. He describes the sublime in terms of a relationship between the faculties of imagination and reason.

Kant characterizes two kinds of sublimity. The mathematical sublime is a feeling of boundlessness or vastness, as caused by reflections on the infinitely large. A pyramid is an example of such a structure, one that cannot be wholly taken in in a single gaze.

The dynamical sublime describes the feeling of being overpowered. This latter sense often comes from natural objects such as the face of a cliff over the sea, or of an enormous thunderhead. Sensations of the mathematical sublime arise from largeness; sensations of the dynamical sublime arise from fear.

I submit that the meaning of games like Drop7 and Orbital are best understood in relation to the sublime, and particularly to the mathematical sublime.

Drop7 asks the player to drop discs emblazoned with a number from one to seven down the columns of a 7×7 grid. Gravity carries them until they reach bottom or stack atop other discs. If a disc’s number matches the quantity of discs in a row or column (no matter their numbers), the matching disc disappears.

Grey discs cannot disappear, until they are unlocked to reveal a number. This is done by causing a numbered disc to disappear adjacent to the grey disc two times. Points are scored for each disappearing disc, with bonuses awarded for chains and board clears.

Much is left to chance in Drop7. The board starts with some discs already in place, and each disc the player must place is drawn randomly. In some cases, a convenient number appears, allowing the player to execute a planned chain or avoid a dangerous situation. In other cases, an undesirable disc forces the player to change plans. Furthermore, when grey discs appear, their contents remain unknown to the player until surrounding discs reveal them.

All together, these mechanics require the player to reassess the state of the board each turn. Grey discs can be taken as uncertainties, but doing so is unwise. It’s much smarter to assume the worst of hidden numbers and plan accordingly.

Yet, even then, each turn requires a total reassessment of the state of the board based on the last turn’s results and the present disc. While emergent consequences exist in chess and go, Drop7 makes the long-term impact of a single move visible even to the amateur player.

The experience of playing Drop7 is thus one of planning present moves against a series of contingent future ones, given a set of slowly changing uncertainties. The vastness of possible moves is calculable for a moment, until it is disrupted by the randomness of new information. This is where the player finds the game’s mathematical sublimity.

Mastery of the game is always temporary, as each move collapses the innumerable possibilities that exist before a disc drops into the fixity of a new situation just after. Yet, unlike the constantly changing dynamics of a chess or go board, each move in Drop7 reveals something more about itself later on, as previously unknowable impacts begin to exert torsion on the present.

In Orbital, the player fires orbs from a rotating gun at the bottom of the playfield. These orbs ricochet off walls and one another, until inertia stops them. Once stopped, the orbs grow until they touch a playfield wall or another ball.

The player’s goal is to break the orbs by striking them three times with new ones (a large counter on each ball shows the current hit count), scoring a point. However, should an orb bounce such that it passes a white line just above the player’s gun, the game is over. Following its cosmic theme, the orbs in play create gravitational fields that alter the path of subsequent ones.

Like Drop7, players of Orbital suffer under an environment dependent on the increasing contingency of aggregate moves. One tactic for play involves estimating the trajectories of orbs based on the friction and gravity of the environment. One can, for example, attempt to lodge a cluster of small orbs in the corners, increasing the likelihood of destroying many with a single shot.

Yet, as each orb settles, it alters the gravity well of a part of the playfield, effectively erasing whatever understanding the player had developed about the earlier topology. Notably, this same disorientation occurs even when the player succeeds, since an exploded orb alters local gravity too.

In Drop7, the mathematical sublime enters the game primarily through chance: the random generation of discs under the grey coverings and in the player’s hand. In Orbital, there is no chance whatsoever. Every move in the game is calculable. Yet, the vastness of the ever-changing universe makes such planning impossible for the human player, who must win out over both timing and physics to carry out a shot intentionally, whether or not it was well-planned in the first place.

Orbital is less forgiving. While Drop7 slowly winnows down choice until the player is overcome by failure, Orbital puts failure on the screen, a thin, fragile line subject to even the lightest graze.

To play Drop7 or Orbital is to practice string theory, to assess the unknown branches of infinite futures. Whether one plays effectively or not, these games force players to reflect upon the mathematical boundlessness of the systems that drive them, systems that alter themselves with every move.

Allegorical Aboutness

Can we say that Drop7 and Orbital are “about” something? And if so what? Here it is useful to return to Murray’s interpretation of Tetris.

One might find a similar mathematical sublimity at work in Tetris, after all. Each block alters the topology of the playfield, the player must alter that topology to continue the game, and chance dictates what pieces might be available to consummate the geometrical promises made earlier.

But Drop7 and Orbital differ from Tetris in an important way: they are turn-based, not continuous. The player must always intervene to make the next move, offering an opportunity to reflect on the enormity of the task, a requirement of sublimity.

When Murray reads Tetris as a work about the Sisyphean toil of work, she refers not to the game’s dynamics of mathematical sublimity, but to the temporal dynamics of its operation. And time, as it happens, is precisely the formal explanation Eskelinen’s offers after his rebuff of Murray’s narrativism.

Office work is generally not a variety of sublimity like the rapidly branching parallel worlds of Drop7 and Orbital, but it is often an experience of time’s arrow, of unstoppable progression, with or without progress.

In Tetris, the method of play disrupts access to the sublime. But in Drop7 and Orbital, the player’s pondering of and reaction to sublimity is enhanced by the mode of action. Arrested between each move, it is possible to allegorize that sensation, taking it as the subject of the game.

For example, Drop7 offers an experience of dread and smallness in the face of unpredictability — not only of the future (the disc to be placed), but also of the past (the unrevealed grey discs). Such an experience feels much like that of, say, personal choice. Should one contribute to the Red Cross? Convert to Islam? Take a mistress?

To be sure, the surface and model of Drop7 do not feel like this at all, but the experience of mathematical sublimity are alike in both cases.

In this respect, one might argue that Drop7 is more about moral choice than are games like Fable or BioShock. The latter titles may simulate the actions of decision, but just like Tetris does for work, they do not capture the theme of choice through dynamics.

Orbital can be seen to build on this theme, but in a different direction. Absent chance, Orbital’s subject revolves around placement. Even given the full knowledge of the physical dynamics of the universe (a subject that finds its way into the visual theme of the game), the human player is still too fallible to succeed at such placement over time. Even the master will be found wanting; after all, the current global high score for Orbital is under 200 points.

This interpretation of these games, one among many, cannot be gleaned from game mechanics, nor from the dynamics those mechanics produce. Instead, they take form in the allegorical exhaust of player sensations between the two.

Puzzling the Sublime

Good puzzle games can do many things. But to call them good based on properties of addictiveness or depth or elegance — the common values used to judge titles like Tetris and Drop7 and Orbital — is to say that abstract games can only exert cold, formal effect on their players. The sublime is just the opposite of cold formalism: a feeling of overwhelm, of vastness, of abundance.

The sublime helps us see the limits of our own reason, showing us the instability and immensity of the world. Surely such a theme hasn’t been exhausted by a few games about blocks and numbers and shapes, just as it hasn’t been captured by a few games about war or sacrifice or loss.

The role of the mathematical sublime in puzzle games should give us pause about our goals as creators and critics. We look for masterpieces in games by comparing them to familiar works of representational art, like film, painting, and literature. But the sublime is found elsewhere: in architecture, in nature, in weather. Perhaps we should look to these sources for inspiration too. (source:gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号