Friendster,Facebook,The Well共同点:拒绝匿名制

还记得Friendster吗?该款社交网站在欧洲并没有太大影响力,但其创建早于MySpace和Facebook等知名社交网站。实际上,正是FriendSter的快速增长导致该网站技术上无力支持广大用户的需求。

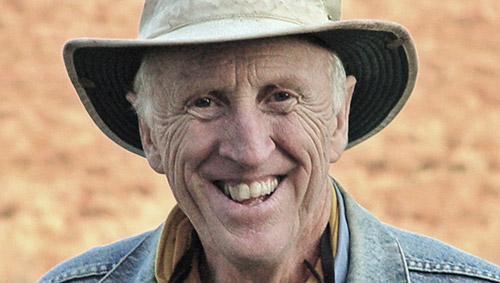

在回溯社交网站的发展史中,我们采访了社交网站Friendster的创办者Jonathan Abram。

据游戏邦了解,2002年的Jonathan Abram已经在多家大型技术公司任职,并开创了自己的一番事业,因此有不少闲暇时间。Jonathan Abram不禁怀疑自己的事业是否已经达到了巅峰时期。

当时,Jonathan Abram身边许多好友纷纷开始使用网络约会网站。然而在的Jonathan Abram看来这类匿名网站并不完善。因此他决定自己创办一个使用真名,将现实社会交往延续至网络世界的网站,便于朋友们进行真实的交流。在Friendster之前,大部分的网络交流都是匿名,网络世界隔绝于现实生活之外。因此,Friendster社交网站的不同之处在于用户使用的是真实姓名,真实照片,与现实世界中的真实朋友进行交流。

Jonathan Abram在发现了这种将现实和虚拟世界结合的方式后,与朋友一起开发了密码保护网站Friendster。然而,病毒式传播渠道却很快盛行于该网站。“人们认为Frindster有趣而实用,希望更多的朋友加入其中因此纷纷邀请朋友加入,导致网站用户迅速增长。”

上线一年内,FriendSter吸引了数百万用户,并获得了多家大牌投资公司的资金支持。

那么究竟是什么方面出现了问题呢?答案是各方各面。之后,Jonathan Abram失去了赞助方的支持,公司的主导权分散给了4位公司执行官,同时网站也出现了重大额技术问题。“该网站仅仅运营了2年。”最终,Jonathan Abram离开了Friendster,投身加入了各种新兴公司的创建。

现在,Friendster变身社交游戏平台仍然时常出现在人们的网络生活中。目前该网站的用户主要集中在亚洲地区。在David Kirkpatrick的著作The Facebook Effect中,Mark Zuckerberg将Friendster的成败引以为戒,并决心绝不因为技术原因造成用户流失。

此前,我们也采访了一位网络社区先锋Stewart Brand,他可谓是加利福尼亚州反文化运动的传奇人物。他曾经创办了类似Facebook的生态组织Whole Earth Catalogue并将其搬至The Well网络。

然而,真正令人惊讶的是:Friendster和Facebook所秉持的成功关键——要求用户使用实名,将现实生活和虚幻网络相结合的做法早在80年代The Well网站就已开始采用。

Stewart Brand拒绝在The Well网络社区中使用匿名。他认为“匿名虽然可以使人们对各种重大事件畅所欲言。但人们也会可以利用匿名的形式毫无节制的骚扰旁人。很多科学家和知名人士也凭借匿名的方式进行各种恶意行为。”

很快地,The Well网络社区兴盛了起来,人们在其中畅谈各种话题,并在现实生活中举办集会延续各种讨论。

然而,这一网络社区并不是伊甸园——Stewart Brand及其他负责人不得不极力控制The Well中出现的各种偏激言论——事实证明这一方式具有顽强的生命力,25年后的今日,The Well网站仍然还在运营。

也许很多人认为Stewart Brand那一年代的人会对Facebook社交网站嗤之以鼻,然而实际上Stewart Brand却指出Mark Zuckerberg与自己有着相同的指导方阵。他认为Facebook坚守实名这一基本理念,打败了很多竞争对手。采用实名制是Facebook公司最宝贵的财富之一。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,转载请注明来源:游戏邦)

Remember Friendster? No, me neither – it never made an impact in Europe. But this was the social network that promised to be the next big thing on the web, before first MySpace and then Facebook ran off with that title. In fact, it grew so fast that it fell over, its technology unable to cope with the surge in demand.

In my journey through the history of social networking I have met Friendster’s founder, another man who can claim to have reinvented the way we communicate.

In 2002 Jonathan Abrams, a Canadian software engineer who’d already worked for major technology firms and started a couple of businesses of his own, found himself with time on his hands. It was the depths of the dotcom crash and he wondered whether his career had already peaked.

He told me that gave him the space to pursue his idea of a website that would enable his friends to run their social lives better. More and more of them were using online dating sites but he saw a major flaw – who knew who the people in the other end really were?

He decided that a place where you used your own name and managed your offline social life with an online presence would be attractive. “Before Friendster,” he explained, “most of the way people used technology was anonymous and they were interacting in a virtual world completely disconnected from the real world. The difference with Friendster was you used your real name, real picture, and interacted with people you met in the real world.”

He was right about the appeal of this merging of the real and virtual worlds. He started with his own friends on a password-protected site, but Friendster rapidly went viral. “People found the site fun and useful, they wanted their friends to be on it so they would bug their friends to join and then it grew exponentially.”

Within a year it had attracted millions of users, lots of excited media coverage, and had won big-name venture-capital backing.

So what went wrong? Just about everything. Abrams fell out with his backers, the firm rapidly went through four chief executives, and there were huge technical problems. “The site barely worked for two years,” is how the founder puts it.

Eventually he left, and has since been involved in a number of other start-ups. We met at his latest venture in San Francisco’s SoMa district, an empty office suite with furniture in boxes, about to become the Founders’ Den, a shared social space for entrepreneurs.

Friendster is still around, advertising itself as a social gaming platform, and apparently enjoying a measure of popularity in Asia, where the majority of its users are now based. But whatever happens to it from now on it has played one vital role – helping Facebook grow without major technical hiccups. David Kirkpatrick’s fascinating book The Facebook Effect, he recounts how Mark Zuckerberg fretted about what had happened to Friendster and determined that his business would not allow technology failure to drive users away.

Earlier I had met a very different and much older online community pioneer. Stewart Brand is something of a legend in the Californian counterculture movement, the man who started the Whole Earth Catalogue, a kind of analogue Facebook group for eco-types, and then took it online with The Well, the Whole Earth ‘lectronic Link.

But what struck me was that the very principles that were later to prove successful at Friendster and Facebook – demanding that members used their real names, mixing offline and online networks – had been tried out in the 1980s at The Well.

Because Stewart Brand decided that the new online community was going to reject the anonymity that was then the norm on bulletin boards and other early computer forums. “This was politically against the grain,” he told me. “The whole idea was that anonymity freed people to say important stuff and all I could see was that anonymity freed people to insult each other without retribution and they did so with abandon. Very responsible corporate people and scientists, when they had the opportunity to speak anonymously they did so with such viciousness and ferocity, it took my breath away.”

Soon the new online community was thriving, its members debating everything from the meaning of life to the nature of sexuality to the merits of different computer operating systems – and then meeting up in the real world to continue the conversations.

This community wasn’t the Garden of Eden – Stewart Brand and other leaders had to try to control the behaviour of “trolls” who began to infest some of the conversations – but it proved sustainable, and is still around 25 years after its birth.

You might think that someone of Stewart Brand’s generation and political background would look askance at the development of Facebook, with its mostly trivial content and its increasingly commercial nature. Not a bit of it

“Facebook is fantastic,” he told me, explaining that he saw some of the same principles in action under Mark Zuckerberg that had governed The Well: “I’m really impressed at a lot of the instincts that Zuckerberg has had. Taking non-anonymity as an absolutely fundamental value of his company and thereby beating off the competition. A Facebook identity is one of the most valuable things his company offers. The lack of anonymity is what gives it value.”

On the internet nobody knows you’re a dog, according to the famous cartoon in the New Yorker. But, if you were to believe the social networking pioneers, Fido would be better off coming clean about his idenitity on his Facebook profile. (source : bbc.co)